The Martians were key allies of the United States in defeating the Axis Powers in the Second World War and emerging as the dominant superpower of the 20th century. In those years, a recurring joke in scientific circles imagined that invaders from Mars had arrived in Hungary in the late 19th century and left after a few years, having decided that our planet was not suitable for them to settle on; but during their brief stay they had had time to mate with some Earthlings and leave behind a few offspring, who eventually became exceptional scientists, with intellectual capacities that seemed out of this world. “They are already here among us; they just call themselves Hungarians,” jokingly declared one of them, Leo Szilard, who was one of the inventors of nuclear energy and who wrote the most important letter Albert Einstein ever sent.

In addition to Leo Szilard (1898-1964), the nucleus of the Martians (a sort of scientific Rat Pack) included Theodore von Kármán (1881-1963), whose ideas propelled the history of aviation, paving the way for jet aircraft and supersonic flight; Edward Teller (1908-2003), designer of the hydrogen bomb; Eugene Wigner (1902-1995), who won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his theories to understand the atomic nucleus and who predicted the existence of today’s “unicorn” of physics; and finally, the most unique Martian of them all, John von Neumann (28 December 1903 – 8 February 1957).

Born as Neumann János Lajos, he is the paradigm of those gifted scientists who were born into middle-class Jewish families in Budapest, grew up in the refined intellectual environment of the same neighbourhood of that city, went to the same high school and then to the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, completed their studies in Germany before fleeing Nazism to settle in the USA, where they all played an important role in the Manhattan project, the first major applied science programme in history. There, in the Los Alamos laboratory, they attracted attention both for their extraordinary intellectual abilities and for their animated chats, whether in their incomprehensible mother tongue or in English with that accent made popular in Hollywood by the Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi as Dracula (1931).

The teenager who solved a great mathematical crisis

As a child, von Neumann had been brought up to speak and write fluent German, French and English, and to be able to get by in Italian, Yiddish, Latin and Ancient Greek. It was also then that his passion for history, especially that of the ancient world, was born. He could have been a historian or a linguist, but what he excelled at above all else was mathematics. He was a child prodigy whose mental calculation skills were such that by the age of six he was already credited with feats such as quickly dividing two eight-digit numbers in his head. At school, his mathematical level was several years ahead of his peers, so his father hired eminent mathematicians such as Gábor Szegő to instruct him. As a result, in 1921, at the age of just 17, he had already made his first major contribution to science: in one of his first research papers he provided the modern definition of ordinal numbers, still used today, which improved on Georg Cantor’s definition. To the surprise of the scientific world and to the delight of David Hilbert, a teenager was showing the way out of a serious identity crisis that the greatest theoretical mathematicians had got themselves into, triggered by Russell’s paradox, discovered by the philosopher and mathematician who won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Such an achievement did not impress János’ father enough to allow him to focus only on mathematics. He agreed to permit him to study mathematics in Budapest only if, at the same time, he pursued studies at the University of Berlin to become a chemical engineer, a profession that Max von Neumann saw as much more lucrative and which would guarantee his son a well-paid position. He fulfilled his father’s requirements and at the same time, in 1926, completed his doctorate in mathematics, which enabled him to pursue his own dream: to enrol at the University of Göttingen as a pupil of David Hilbert.

A driving force of the major scientific revolutions

There he began a period of vertiginous scientific production (1927-1929), at a rate of nearly one major paper a month with crucial contributions to mathematics. He covered innumerable fields of research, earning himself the reputation of being the “last representative of the great mathematicians who were equally at home in both pure and applied mathematics.” When asked to highlight one single accomplishment from those years, John von Neumann, now a mature scientist, chose the rigorous mathematical framework he brought to quantum mechanics, solidifying the revolution of this young discipline, which had taken its first steps at the same time as little János. That alone would have been enough to earn him a place in the history of contemporary science, but he accomplished so much more.

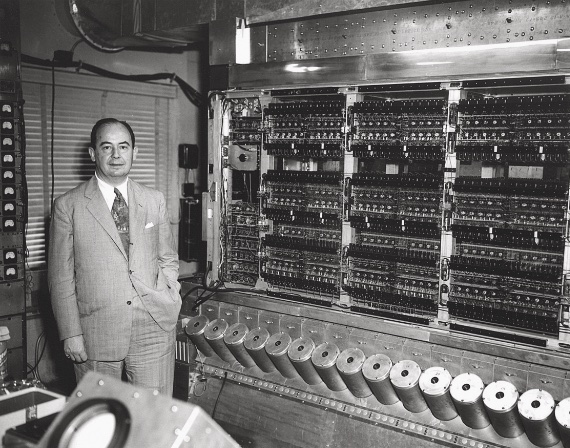

The fingerprints of John von Neumann are all over the major scientific revolutions of the 20th century, as he left his mark of genius on a wide range of fields. Looking back over many of these stories reveals a foundational article by him, a visionary prediction or an inspirational connection of disciplines that opened the minds of the great innovators in those fields. Once settled at Princeton University and renamed John, he worked on the philosophy of artificial intelligence with Alan Turing. He was involved in the development of ENIAC, the first complete computer, which in 1945 finally had the four basic features of our current computers. He laid the theoretical foundations for computer viruses, developing in 1949 the concept of automata capable of reproducing themselves, following processes like those later seen in living organisms when the structure of DNA was discovered. He sowed ideas of quantum information theory that were later taken up by Claude Shannon, the forgotten inventor of the digital age. He led the team that produced the first computerised weather report in 1950, with a 24-hour forecast, and in 1955 warned of global warming caused by human activity and proposed possible geo-engineering technologies to control the climate. He founded game theory, which was later developed by several Nobel laureates such as John Nash. And he is also credited with the equilibrium strategy, based on mutually assured destruction, which governed geopolitics during the Cold War.

Unmatchable speed, boundless curiosity

His knowledge of history and warfare, in addition to his political convictions, also led him to anticipate some key factors in the outbreak of the Second World War and to place his trust in the United States as the power to stop the Nazis. His mental agility and astonishing memory—he was able to recite verbatim from texts he had read years before—made him stand out even in an environment where some of the most brilliant minds of his time were working. Even among the other Martians—those masters of connecting seemingly unrelated scientific disciplines—von Neumann’s creativity and speed were unmatchable. Edward Teller acknowledged that he “never could keep up with him” and added: “Von Neumann would carry on a conversation with my three-year-old son, and the two of them would talk as equals, and I sometimes wondered if he used the same principle when he talked to the rest of us.” Eugene Wigner also claimed that he did not know anyone as quick and sharp as von Neumann, despite his close dealings with science icons such as Albert Einstein, Paul Dirac, Werner Heisenberg and Max Planck.

For Claude Shannon he was, without a doubt, “the smartest person I’ve ever met.” The recent biography The Man from the Future, by Ananyo Bhattacharya, delves into the figure of John von Neumann: both into the genius of the great mathematician admired by his colleagues and into the experiences of the character who went out partying all night several times a week, who annoyed other distinguished Princeton professors—including Einstein by playing loud German marching music in his office—and who was a fan of smutty jokes and gossip even on his deathbed. Von Neumann died at the age of 53, losing a battle with cancer that prevented him from winning one or more Nobel Prizes, for which he would surely have been a candidate despite being a mathematician. Unfortunately, he did not live to witness the rest of the 20th century unfold, a period that saw the fruition of many of his theories, practical ideas and predictions that sprang from his prodigious mind and boundless curiosity.

Francisco Doménech

@fucolin

Comments on this publication