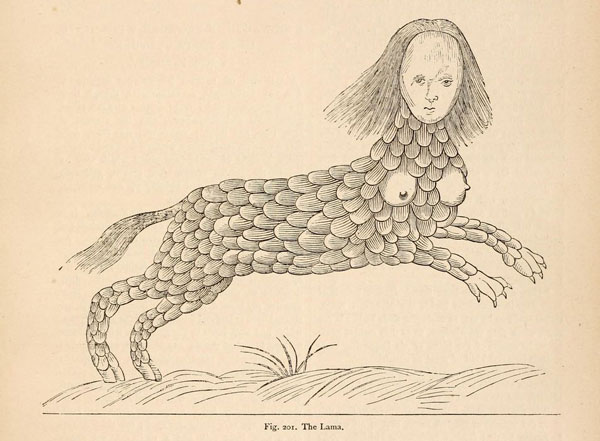

If we could travel through time to Victorian England, we would be amazed to find striking illustrations of nature in the sensationalist tabloids of the epoch. Among them there were some known as science gossip. On their pages, rigorous drawings coexisted with impossible creatures, like one unusual half-dog/half-human specimen. The authors of these images, both renowned scientists and enthusiasts of the natural world, sought to promote scientific knowledge among the public. Currently, the Biodiversity Heritage Library is working on classifying the pages of these journals in a digital citizen science project, so that the information they contain does not fall into oblivion.

The first scientific journals in history appeared almost simultaneously, in 1665, on both sides of the English Channel: Journal des Sçavans in France and Philosophical Transactions in England. In these publications, forerunners of today’s Nature and Science journals, Newton first explained that light was composed of elementary colours, and the father of microbiology, Leeuwenhoek, detailed how he saw small animals through the microscopes he manufactured himself. The French Revolution in 1789 put an end to the regular publication of Journal des Sçavans, which did not return until 1816 when it was revived as a literary journal with hardly any outstanding scientific material. For its part, Philosophical Transactions has been continuously published to this day, making it the oldest scientific journal. Over time, the number of titles of this sort grew and diversified, until the explosive success of gossip science in the nineteenth century during the reign of Britain’s Queen Victoria from 1837 to 1901.

Before there were cameras, researchers had to make detailed drawings to describe their observations and work. Those illustrations began to be published, especially in Victorian periodicals, including Science Gossip, Recreative Science and The Intellectual Observer. In contrast to previous publications, their authors were not only scientists, but also included nature lovers. “Victorian research was very different from research done today. It was largely driven by amateur scientists who were not necessarily trained in scientific observation but had a deep enthusiasm for the natural world,” explains Trish Rose-Sandler of the Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL), the global library consortium of natural history museums.

Illustrations to document species

These journals without too much rigour were aimed at curious members of the public and students. On their pages could be found drawings without any scientific basis, but also others that meticulously described species of the moment. “These illustrations serve to document life on earth. With the current changes in global climate patterns and the rapid loss of natural habitat for many species, in some cases the historic illustrations contained within these texts represent the only available image documenting a species,” says Rose-Sandler. The BHL project harnesses the power of citizen science to engage the whole world through the Internet in order to classify and describe these drawings, which in some cases are the only known record of extinct species. An example is the description of a group of rare orchids in Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, which is the only source of current knowledge about these flowers because they disappeared due to excessive collecting.

Through the website www.sciencegossip.org, anyone interested can help detail the pages of science gossip, so that exploring its content is easy. The BHL project aims to prevent the loss of data on the biodiversity of the 19th century, and also to better understand how the extinction of some species occurred. “The research on species can now be done much more efficiently and accurately because researchers now have comprehensive access to the literature they need to make conservation decisions. We might prevent similar situations in the future,” says Rose-Sandler.

Despite the popularisation of science sparked by Victorian science gossip —scientific journals grew from just 10 in 1700 to 10,000 by 1900— the frivolous ones were forced to close due to the increasing professionalisation of science, especially in the 19th century. Even so, today they have heirs, such as the famous Popular Science founded in 1872, specialising in science and technology news aimed at non-specialised audiences. On occasion, this publication has received criticism for favouring sensationalism in its articles over rigour, but almost 150 years later they continue to avoid aseptic and unattractive headlines in their editions published in 45 countries and 30 different languages.

Comments on this publication