When climatologist James Hansen testified before the US Senate in 1988 that human-induced increases in atmospheric CO2 were changing the climate, it was the beginning of the popularisation of an idea that has taken decades to take hold. But it was also the culmination of a scientific journey that began in the 1820s, when Joseph Fourier discovered that the Earth was warmer than it should be and that human activity might be having an influence. In 1856, Eunice Newton Foote suggested that CO2 in the atmosphere retained heat, pointing to the greenhouse effect that was later demonstrated by John Tyndall and quantified by Svante Arrhenius in 1896. From 1958, Charles David Keeling’s CO2 measurements in Hawaii began to document the increase in the greenhouse effect. But between Arrhenius and Keeling lies an essential piece of the puzzle that is often unjustly forgotten: Guy Callendar.

Guy Stewart Callendar (9 February 1898 – 3 October 1964) had an illustrious parent who exerted a powerful influence on him: his father, the British physicist Hugh Longbourne Callendar, who worked at the Cavendish Laboratory as a student of Joseph John Thomson, credited with the discovery of the electron. Callendar senior had a university education, but not in physics, and was a man of many different interests: sports, nature, astronomy, invention and even shorthand, creating a system that Thomson learnt and used. In physics he excelled in thermometry and thermodynamics, and was nominated for the Nobel Prize.

But above all, he had a passion for the new inventions of the day—automobiles and motorcycles—a passion that Guy inherited. The second of Hugh’s four sons was born in Montreal, where the family had temporarily moved. Guy followed in the footsteps of his father, whose laboratory at Imperial College London he joined on his return to England, even before he began his studies in mechanics and mathematics. His work focused on steam engines, but he soon began to devote his spare time to another area of particular interest to him: meteorology and climate.

Data to demonstrate the effect of CO2 on temperature

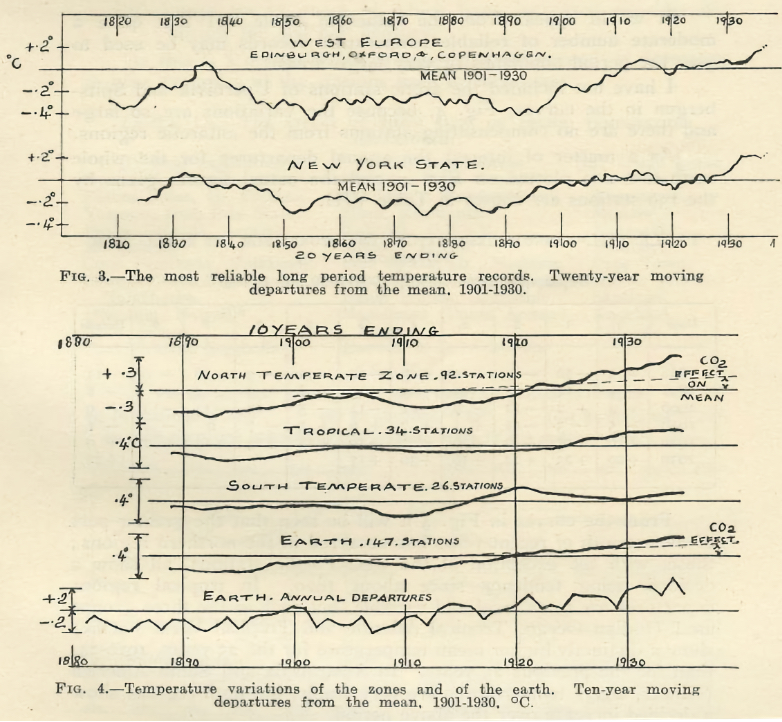

Following in the steps of Arrhenius and his colleague Nils Gustaf Ekholm, another pioneering proponent of the effect of anthropogenic CO2 on global warming, Callendar began in 1934 to gather detailed temperature data over the years, averaging global mean temperatures from records published by the Smithsonian Institution and other sources. In parallel, he collected available data to calculate how much CO2 was being emitted into the atmosphere by the burning of fossil fuels, estimating a figure of 4.3 billion tonnes for 1938.

Callendar correlated the two parameters, and in 1938 published his paper “The Artificial Production of Carbon Dioxide and its Influence on Temperature” in the Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. He calculated that over the previous half-century, the temperature had risen at a rate of 0.005°C per year due to this artificial production of CO2, showing for the first time that what his predecessors had speculated was real and was already happening.

The study, however, was met with great scepticism. Callendar was seen as the classic gentleman scientist of yesteryear, an amateur with no specific training who did science as a hobby. But his conclusions went far beyond showing a simple correlation. At the time, some experts objected that the high concentration of water vapour in the atmosphere, a powerful greenhouse gas, dwarfed any possible contribution from CO2. Callendar countered by showing that CO2, concentrated at higher altitudes than water vapour and persisting for hundreds of years, traps heat at wavelengths that escape water vapour, meaning that the greenhouse effect contributed by carbon dioxide is cumulative with that of water vapour.

A forecast that fell short

But despite the harsh criticism of his study, Callendar continued to defend his theory until his death in 1964, and the effect named after him continued to be discussed, with more and more evidence in its favour. Although his data were challenged as having been obtained by collecting and averaging fragmentary records from different sources, Keeling’s measurements, collected in a single place and in a systematic and consistent way, proved Callendar right. In fact, a comparison of his graphs with historical estimates based on current data is incredibly accurate.

The only area where this now vindicated pioneer erred was in his prediction of the consequences: like many in the past and some still today, he foresaw benefits from this global warming: “The combustion of fossil fuel […] is likely to prove beneficial to mankind in several ways, besides the provision of heat and power,” he wrote. He mentioned crops in northern regions as an example, and added: “In any case, the return of the deadly glaciers should be delayed indefinitely.”

Of course, while he was right about his retrospective data, he fell far short in his long-term forecasts: he predicted a temperature rise of 0.39°C for the 21st century, a far cry from the 1.5°C frontier we are already on the verge of reaching. Little did Callendar imagine that the effects of climate change would become one of the most feared planetary scourges of our time. And little did he know that his beloved motorcycles would be part of the problem.

Javier Yanes

Main picture credit: GS Callendar /Wikipedia / Welgos/Getty Images

Comments on this publication