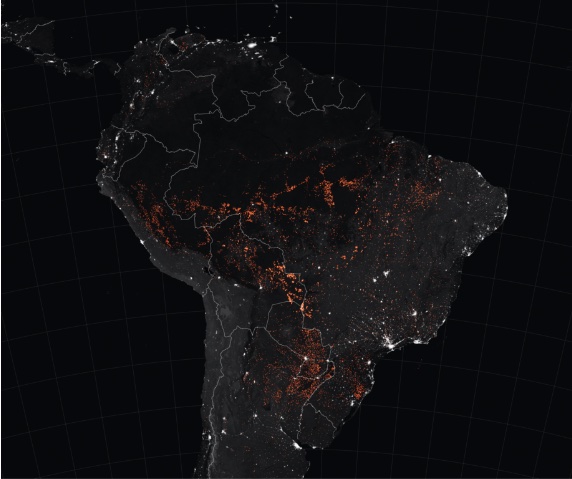

The world was shocked in 2019 when news reports told of an explosive epidemic of fires in the Amazon, and satellite images showed what from space literally looked like a continent ablaze. But the 9,000 square kilometres of forest burned were dwarfed by the more than 240,000 that were scorched in Australia in the 2019-20 season, an area similar in size to the UK. Wildfires are one of the greatest threats to nature and its inhabitants—including humans—and one that is becoming more pressing as a result of climate change. And yet, the curious paradox is that fire has not only been a natural part of terrestrial cycles for millennia, but that certain ecosystems even depend on it for their survival; used properly and in the right places, fire can also be an ally of sustainability.

In its Sixth Assessment Report, published in 2021-22, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) found that “in the Amazon, Australia, North America, Siberia and other regions, wildfires are burning wider areas than in the past.” Scientists are extremely cautious about attributing specific phenomena to climate change, which they don’t do without sufficient evidence; experts believe there is such evidence in the case of western North America, where this factor has been responsible for the aridity and drought that have almost doubled forest fires compared to a scenario without climate change. Global warming is also suspected to be involved in Australia’s fires, as 2019 was the country’s hottest and driest year on record; only 1% of the fires were arson, and the vast majority were due to the effect of lightning strikes on parched vegetation.

In turn, the increased number of fires feeds back into climate change, as carbon stored in biomass is released into the atmosphere and fuels the greenhouse effect. One study estimated that Australia’s fires released 715 million tonnes of CO2, an amount that alone is at least a third more than the country’s typical emissions for an entire year.

This whole picture portrays fire as a destructive force and one of the great enemies of the planet and of humanity. Yet fire has always been here: the fossil carbon record, a geological testimony to fire, dates back at least 420 million years, almost as far back as the emergence of plants. And like everything else that species on Earth have had to coexist with throughout their evolution, many have found ways to adapt, so much so that some even need fire to flourish: “Wildfire is a natural and essential part of many forest, woodland and grassland ecosystems, killing pests, releasing plant seeds to sprout, thinning out small trees and serving other functions essential for ecosystem health,” says the IPCC.

Controlled fires to manage ecosystems

Ever since our appearance on this planet, humans have used fire for agriculture, hunting and gathering, renewing vegetation and cultivated fields, exposing the minerals in soil and promoting germination. Human use of fire has altered both landscapes and natural fire regimes. However, this began to change in the 19th and especially the 20th century: first, the expansion of agriculture and ranching in countries such as the USA ended the use of fire by indigenous populations. In the early 20th century, total fire suppression policies were instituted and were mirrored in many countries. Despite the influence of climate, policies and changes in land use have led to a large reduction in forest fires.

But in recent decades, what some experts call a paradigm shift has occurred. Some uses of fire have persisted, such as opening firebreaks or burning off excess forest fuel during the winter to prevent more uncontrolled fires in the hot months. But in the 1990s, the US began to introduce the greater use of prescribed burning as an ecosystem management tool. “Fire was allowed to burn without suppression in more remote areas in the 1990s, and that is still largely true today,” Richard Hutto, professor emeritus specialising in fire ecology at the University of Montana, tells OpenMind. “Because severe fire is a natural part of conifer forest communities, there are numerous plant and animal species that depend on severe fires that kill most of the trees.”

In particular, some species of conifer are among those that need fire: redwood cones depend on it to open and release seeds, and this species is abundant in the state of California, which has been a pioneer in fire management since the late 1960s. In Yosemite National Park, “they’ve been doing this for around 50 years now and this has generated some big benefits,” Scott Stephens, a professor of environmental fire science at UC Berkeley, tells OpenMind. In a recent study, Stephens and his collaborators show that in some areas of Yosemite and Sequoia-Kings Canyon Parks, fire has reduced forest cover by 20%, promoted shrub and grassland growth, increased summer soil moisture by 30%, boosted species diversity, decreased drought-induced tree mortality and facilitated adaptation to climate change.

Tool against pests

Another benefit of fire management is the elimination of pests, both those that affect vegetation and those that attack animals and humans. A recent study led by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service suggests that the implementation of fire suppression policies over the past century may have contributed to the increase in tick-transmitted diseases, which now account for more than 75% of vector-borne infections.

Fire not only kills these parasites directly; according to the authors, fire-tolerant species such as pine, oak and chestnut were prevalent in the eastern forests of North America before the arrival of Europeans. Fires thinned the undergrowth and created conditions of high temperature and low humidity that kept ticks at bay. As this ancestral relationship between forests and fire was broken, the forests and the animals that inhabit them changed, decreasing the ticks’ natural predators and increasing the population of small mammal hosts. According to study leader Michael Gallagher of the USDA, “there’s an opportunity to reduce the number of ticks by using prescribed fire to restore the health of forest ecosystems.”

But in the face of all this, where does that leave the threat of the carbon released by fire? Proponents of fire management argue that controlled use of this resource will prevent the greater evil of massive, uncontrolled fires. According to the IPCC, “fire emissions are not necessarily a net source of carbon into the atmosphere,”; vegetation regrowing after a fire can recapture an amount of carbon almost equivalent to that released by fire, over a period of one to a few years in grasslands and agricultural lands, or decades in the case of forests, provided they are not replaced by another land use.

“Most people have no clue about the naturalness and necessity of severe fire,” Hutto concludes. Fire ecologists are working with the paradigm shift, but they still have to fight for a change in mentality, to convince the public and the authorities that fire can also be a friend and, if we know how to handle it, an ally against the worst version of itself.

Comments on this publication