Edward Jenner, Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister are the precursors of immunology, the germinal theory of infectious diseases and asepsis, respectively. Vaccinations, epidemiology and sterilization and disinfectant measures are now fundamental tools in the race against the COVID-19 virus, a global pandemic as defined by WHO, that has spread to over 200 countries in just a few months, according to UN data.

In the face of this new public health challenge for the entire planet, society is impatiently waiting for a new defining moment for science in which the key to stopping the SARS-CoV-2 is found. In the meantime, the effects of other great scientific moments are currently the tools being used in the front lines to fight against COVID-19.

Edward Jenner and the birth of immunology

The British doctor Edward Anthony Jenner (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) gave the first vaccination in history in 1796. Known as the “father of immunology”, his work is one of the discoveries that has saved the most lives in history.

The concept of vaccination did not arise from Jenner having a “Eureka moment”. The practice of variolation or the inoculation of smallpox scabs spread from China and India to the west as a protective measure among working-class groups in society. Its success was debatable and could have fatal consequences in a high percentage of cases. In parallel, several doctors had noted that farmers and milk maids caught a more benign version of the disease, cowpox. Jenner connected the dots and selected the first patient: his gardner’s son. With a practice that was not without controversy, but which did provide striking results since the beginning, Jenner inoculated the child with the benign version of the disease. This opened the door to an essential ally for health, the attenuated microorganisms that allow us to fight against human diseases.

At the time of its discovery, although smallpox vaccination was accepted as approved in several countries, Jenner was missing several fundamental concepts to square the circle of infectious diseases as the existence of pathogens had not yet been discovered. WHO declared smallpox eradicated in 1980, which is estimated to have caused around 300 deaths in the 20th Century alone.

Louis Pasteur and the siege on pathogenic microbes

The French chemist and bacteriologist Louis Pasteur (December 27, 1822 – September 28, 1895) is another one of the scientists that has saved the most lives with his work. The development of the microbic theory of disease, one of the most important public health advances in history, laid the foundations for the design of effective hygiene methods, vaccinations and antibiotics. Understanding what germs and pathogens are and how they act allowed Pasteur, and many other scientists at the time to create vaccinations against diseases like rabies, tetanus and diphtheria.

The trigger for all these advances was the pasteurization method that the French chemist developed to prevent the contamination of foods and drinks by pathogens. In this process, Pasteur discovered that the microorganisms that caused the food spoilage could also be identified as the cause of certain infectious human diseases that could spread among individuals. These pathogens were the key that Jenner was missing.

The Pasteur Institute laid the foundation for modern vaccinations and microbiology thanks to the work of numerous scientists who participated in different areas of research throughout history. In 1983, the Paris headquarters of the Pasteur Institute was the laboratory that managed to isolate HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

Joseph Lister and the application of asepsis

Joseph Lister (5 April 1827 – 10 February 1912) was a surgeon. He studied botany and later medicine. His father was one of the precursors of the use of the microscope. Perhaps due to a combination of all of these things, he was able to understand Louis Pasteur’s research perfectly and apply it to his area of work: the hospital.

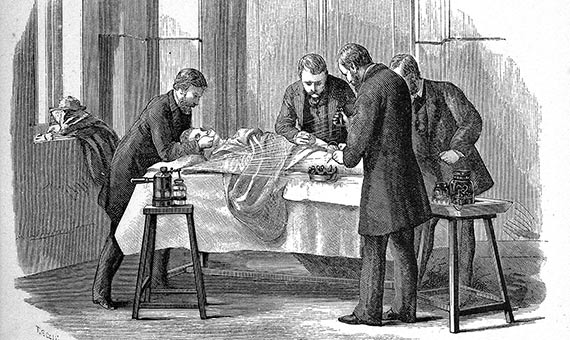

At the time when Lister was working as a doctor, it was assumed that hospitals were inevitably ridden with infection and putrefaction. Operation rooms were the hottest place and in fact, infections in hospitals became known as operating room and hospital fevers. In 1864, Lister found Louis Pasteur’s work, discovering that the fermentation process was due to germs, the microbes that are invisible to the human eye. He therefore believed that the same reasoning could be applied to what happened to surgery patients and their wounds. He analyzed samples of patients’ tissue and decided to try to place an antiseptic shield in between the wounds and the environment. To do so, he used phenol, which he used to douse the bandages, wash the instruments and his hands.

With a series of articles published in The Lancet, Lister explained the bacterial origin of infections in wounds and the methods to fight against them. His theories took root, not without resistance and skepticism, but saving millions of lives since then. Even today, the first defense against many infectious diseases in and out of hospitals is to use good hygiene and wash your hands.

Comments on this publication