Many diseases originate from an agent that we can fight, such as infectious pathogens, uncontrolled cells in cancer, or toxic compounds. But what if the disease comes from the factory in each of our cells, forming part of the genes? Gene therapy—correcting disease-causing genes—seems almost like science fiction. But while it is still far from a routine medical practice, it has now emerged from its troubled beginnings to join the arsenal of weapons against disease.

Scientific observations of hereditary diseases date back to at least the 18th century. In 1902, Archibald Garrod described the inheritance of alkaptonuria—a mutation that causes dark urine—according to Mendel’s laws, which were rediscovered in the early 20th century. In 1983, a gene on a chromosome that is responsible for a genetic disease was mapped for the first time: the huntingtin gene, which causes Huntington’s disease. Today, thousands of diseases caused by genes are known, and more than 6,000 fall into the category of so-called rare diseases.

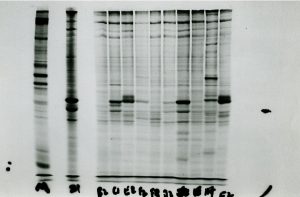

In the 1960s and 1970s, with a clear understanding of DNA and genetic inheritance, and with the first experiments demonstrating the stable introduction of exogenous genes into cells, the concept of gene therapy began to be developed. In the mid-1970s, the first vectors, modified viruses or bacterial plasmids—circular strands of DNA into which exogenous genes can be inserted—containing human genes to complement or correct their defects in cells, were prepared and tested in animals. At the same time, the debate on their ethical implications and regulation began.

The first trials

The first human gene therapy trial took place in 1980, although it is not exactly an exemplary story. UCLA geneticist Martin Cline transferred the beta globin gene into the bone marrow cells of two patients with beta thalassaemia, a deficiency of the blood protein, one of the buildings blocks of haemoglobin. He then reintroduced the cells into the patients’ bodies, following a procedure he had successfully tested in mice. However, Cline did this without the approval of his university, which cost him the loss of his professorship and funding. In any case, the experiment did not work.

The first formal, authorised clinical trial took place in 1990, when William French Anderson, Michael Blaese, Steven Rosenberg and their collaborators at the US National Institutes of Health treated four-year-old Ashanti DeSilva, who had severe combined adenosine deaminase deficiency immunodeficiency (ADA SCID). The insertion of a retroviral vector with the correct copy of the gene was successful, and the girl grew up to be a healthy adult with sufficient immune protection.

It was the beginning of a boom: over the next 10 years, some 300 gene therapy clinical trials were carried out on 3,000 patients. But the slowdown came at the turn of the century, when several deaths occurred, most notably that of the young Jesse Gelsinger, who was being treated for a liver metabolic disorder. These tragic failures forced a radical rethink, but gene therapy has made a comeback.

Universality and costs

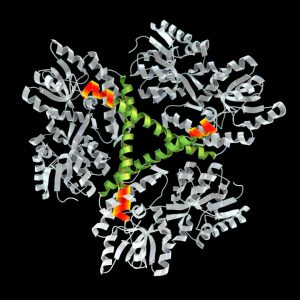

Today it is not only applied to genetic diseases, but also to other illnesses such as cancer. There are different procedures, such as microinjection of genes into cells or their introduction by means of electrical pulses, lipid bubbles or modified viruses, especially the so-called adeno-associated virus (AAV). The therapy can be applied ex vivo, in cells taken from the patient and then reintegrated into the patient’s body, or directly in vivo. In 2017, the first of these, Luxturna, was approved for Leber congenital amaurosis, a rare inherited eye disease.

The road has not been free of new failures and some deaths attributed to the toxicity of VAA at high doses, which has forced the modification of the protocols. But there are now around thirty gene therapies approved in the US and Europe, and more than a thousand clinical trials under way. The greatest successes are being achieved against diseases of the blood and the eye, a relatively isolated and accessible organ that is easier to target and less controlled by the immune system, which in many cases is an obstacle to the proper functioning of these therapies.

In 2023, the first gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy was approved, under the name Elevidys. And the first gene therapy using the CRISPR gene editing system, a molecular scissors for cutting and pasting genes that has revolutionised the world of research, was also given the green light in Europe and the US. This new therapy, called Casgevy, is being applied to the ex vivo treatment of two blood disorders, sickle cell anaemia and beta thalassaemia.

However, the future of gene therapy faces a major hurdle: the most expensive drugs on the market. Elevidys costs $3.2 million per patient, and Luxturna is priced at $850,000. In a country like Spain, which has a universal health system, Luxturna is covered by the public health system. But only a radical reduction in prices, which could be brought about by more widespread use, would ensure that gene therapy is not just a hope for the few.

Comments on this publication