With 14.1 million new cases of cancer and 8.2 million deaths caused by this disease per year worldwide, according to data published at the end of 2015 by the journal Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, eliminating this disease has become one of the main goals of scientists around the world. The traditional use of drugs (chemotherapy), radiation (radiotherapy) and surgery for cancer are being joined by a whole new arsenal of less aggressive and more effective therapies aimed at making it difficult for tumor cells to grow and spread in the body.

What makes cancer such a difficult disease to tackle is that it is the damaged part of the cell itself that loses control, starting to behave aggressively and multiplying indefinitely, ignoring any external signal. In other words, the enemy is within. The trouble is that a single cell, “misguided” by a cancerous mutation, can end the life of a human being within months. Conventional treatments were designed to destroy the cancerous cells, but it was almost impossible not to simultaneously damage healthy tissue.

Tumor cells’ suicide

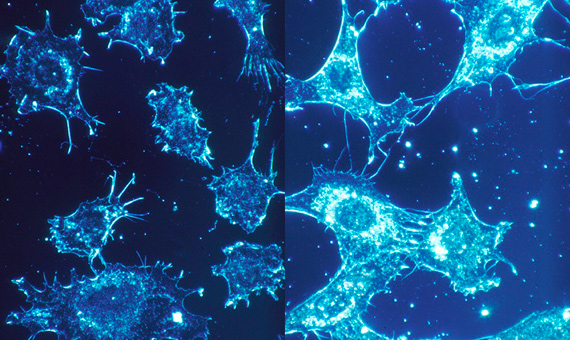

“In essence, cancer cells are hard to kill because they have genetic variants of our own cells and, being so similar, it becomes very difficult to choose therapies that selectively destroy them without harming the healthy ones,” reflects Michael R. King, a Biomedical Engineering researcher at Cornell University (USA). For this reason, he and his team, rather than seeking new weapons to kill the tumor cells “with bullets,” have chosen to push them to commit suicide or apoptosis (programmed cell death).

After all, inducing apoptosis seems the most natural strategy to end cancer. “All cells are programmed to die when they are no longer useful, to prevent overgrowth or when they suffer damage to their DNA,” says King. “The problem with cancer cells is that this natural programmed death is defective,” adds the scientist, who says that his research only aims to “restore an essential function of the cell.”

In his laboratory, King and his colleagues have worked with the TRAIL protein, which they have transported in white blood cells through the blood or lymphatic system to the cancer cells, “where the protein triggers the cellular machinery that makes these cells take their own lives.” After achieving a success rate of 60% in experiments with mice, the challenge now is “to prove that the therapy would work safely in large animals and humans, and we’re working on that, in addition to trying to adapt the treatment to prostate, colon and breast cancer, the most common in the West.”

Isolating the enemy

As good war strategists, oncologists are also considering the option of isolating the enemy instead of destroying it, an alternative designed to end cancer without causing a scratch on any healthy cells. And this makes a lot of sense when you consider that the greatest danger of cancer is its ability to form some invasive structures in the shape of a foot, the invadopodia, allowing them to travel to any part of the body and spread, causing what is known as metastasis. In this regard, the figures speak for themselves: 90% of cancer deaths are caused directly or indirectly by metastases.

In fact, in most cases where surgery does not eliminate the tumor, it is because some diseased cells have spread. If the mobility of blood cells were blocked or they were prevented from forming capillaries and arteries (angiogenesis) to enter the bloodstream and make provisions to conquer new tissue, the cancer would find it very difficult to develop. Another way to stop it in its tracks would be to block a protein called THSB2, which according to a recent study by the Francis Crick Institute (UK) allows cancer cells to create a pleasant environment in which to grow and form new tumors.

Immunotherapy

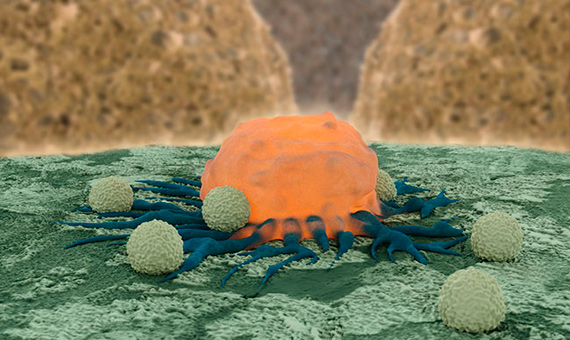

The third tactic that could end cancer is to train the immune system to recognize tumor cells and attack them in the same way as it fights invasions by bacteria, viruses and other microorganisms. Or, put another way, “using certain parts of the immune system of an individual to fight the disease,” as immunotherapy is defined by Charles Drake, co-director of the Immunology Division of the Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, John Hopkins University (USA). This technique, which took its first steps in the early twentieth century, has rapidly evolved into one of the principal lines of research in the treatment of cancer.

Drake has been at the forefront of research in immunotherapy against kidney cancer, and acknowledges that he wasn’t sure about it at first. “We were afraid, since it had the potential to over-activate the immune system, which is why we started gradually,” says the researcher, who in his first trials used a drug called nivolumab. Fortunately, the results were very positive, and in just a few months they managed to put the tumor of the first patient into complete remission. There was the added advantage that this option had far fewer side effects than conventional treatments.

Since then, immunotherapy has been approved for use in the treatment of renal cancer, melanoma or skin cancer and certain types of lung cancer. And in 2015 it received a major boost with the approval by the Food and Drug Administration of the first therapeutic cancer vaccine, sipuleucel-T, capable of extending by four months the survival of patients with prostate cancer.

However, immunotherapy is not without its drawbacks. The main problem is that it doesn’t work for all patients, so one of the challenges for Drake and others doing research in this area is to understand how it works at the cellular level and how to determine, in the clinic, in a simple way, which individuals will benefit from the treatment and which won’t. For now, reflects Drake, what is beyond doubt is that “these treatments are completely changing the way we fight cancer.”

Comments on this publication