Spain’s contribution to engineering at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century was marked by great inventors who designed devices that traversed borders, thus contributing to technological advances and the progress of all humankind.

Isaac Peral’s submarine, Juan de la Cierva’s gyroplane — a precursor to the helicopter —, Torres Quevedo’s cable car, and Alejandro Goicoechea’s articulated train are some of the major inventions that placed Spain on the forefront of world engineering.

Among this group of Spanish innovators was the less well-known, yet ahead-of-his-time inventor, Emilio Herrera. This scientist dreamed about reaching the stratosphere and ended up becoming one of the most notable figures of his time in the field of aeronautics.

A calling to fly

Emilio Herrera was born in Granada in 1879 into a bourgeois family. From a very young age he was passionate about aviation and aerostatics, influenced both by his father — who made his career in the military and organized scientific fairs and conferences — and the novels of Jules Verne who Emilio read as a child.

Raised in an atmosphere of curiosity and scientific interest, he joined the army with the intention of studying aerospace engineering at the Engineers Academy in Guadalajara. After graduating, he specialized in aerostats, popularly known as hot-air balloons. Early in his career with the army, he served in the air balloon regiment and participated in military campaigns in North Africa. He became the first man to cross the Strait of Gibraltar by air.

His accomplishments earned him the friendship and recognition of King Alfonso XIII. During the 1920s, he focused on research and studied different fields within aeronautics: from his collaboration with Juan de la Cierva inventing the gyroplane to the design of one of the most advanced wind tunnels of the time, located in Cuatro Vientos in Madrid.

After the abdication of the king, Emilio accompanied Alfonso XIII in exile in Paris, but he was faced with a dilemma: he had sworn loyalty to the king and he was a staunch monarchist, but he also felt a deep commitment to Spain. It was the king himself who suggested that Herrera return to Spain.

The space suit, 30 years before its time

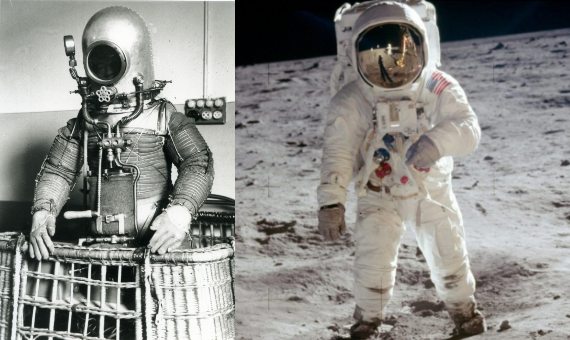

Having returned to Spain, Herrera set off on what was his most ambitious project: to reach the stratosphere in a balloon for the purposes of research and investigation. In 1928, the aeronaut Benito Molas and his crew had already tried to reach stratospheric heights, but they died in the attempt from a lack of oxygen. Knowing the fate of his precursors, Herrera went to work on building a balloon that would be able to travel above 20,000 meters (65,600 feet) and, more importantly, creating a suit that could insulate the pilot from the cold and pressure, provide him with oxygen, all the while giving him the mobility he would need during the expedition.

He incorporated three layers in the design of his suit: one layer of wool, another of rubber, and another of a fabric reinforced with steel cables, all this wrapped in an exterior layer of silver that prevented overheating. The cylindrical helmet was made of steel covered in aluminum with triple-glazed glass to avoid radiation, and it was equipped with a microphone for radio communications. The joints of the suit were designed like an accordion to facilitate movement.

Thirty years later, the prototype, a feat for its time, would inspire NASA when the U.S. space agency was creating space suits for its astronauts, including those worn by the crew on the Apollo 11 mission to the moon. According to his assistant, the Americans asked Herrera to collaborate with the space program, but he refused because they would not allow a Spanish flag to be unfurled on the moon. In appreciation of Herrera’s work, none other than Neil Armstrong delivered a lunar rock to one of Herrera’s disciples and NASA employee, Manuel Casajust Rodriguez.

A dream cut short

Herrera’s dream was not to be. The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War put an end to his experiment. Despite his conservative ideology and loyalty to the monarchy, guided by a liberal and democratic mentality, he remained loyal to Spain’s Republic. When the war ended, Herrera stayed in exile, first in South America, and later in France, where he lived until his death. He was able to live off patents and collaborations with magazines specializing in aeronautics and nuclear energy.

Under World War Two’s Vichy regime, the Germans offered him a job with the Third Reich, a proposition he refused. Also while in France, he became interested in astrophysics and the theory of relativity, which led him to establish a friendship with Albert Einstein, who intervened on Herrera’s behalf helping him secure a position with UNESCO as a nuclear physics consultant.

In his final years he was heavily involved in Spain’s republic in exile, for which he served as president for two years. He never abandoned research and investigation nor the dissemination of scientific ideas.

Emilio Herrera died in 1967 at 88 in Geneva. The Spanish government, purely motivated by political reasons, never recognized Herrera’s achievements during his lifetime; however, this did not prevent international acclaim for his work. Today, this important figure in Spanish history has been vindicated, his memory redressed by the likes of Pedro Duque, the first Spaniard to travel to outer space, and as such, an heir to the visionary who had a dream that was cut short.

Comments on this publication