Given that going viral on the Internet is often cyclical, it should come as no surprise that an app that made its debut in 2017 has once again surged in popularity. FaceApp applies various transformations to the image of any face, but the option that ages facial features has been especially popular. However, the fun has been accompanied by controversy; since biometric systems are replacing access passwords, is it wise to freely offer up our image and our personal data? The truth is that today the face is ceasing to be as non-transferable as it used to be, and in just a few years it could be more hackable than the password of a lifetime.

Our countenance is the most recognisable key to social relationships. We might have doubts when hearing a voice on the phone, but never when looking at the face of a familiar person. In the 1960s, a handful of pioneering researchers began training computers to recognise human faces, although it was not until the 1990s that this technology really began to take off. Facial recognition algorithms have improved to such an extent that since 1993 their error rate has been halved every two years. When it comes to recognising unfamiliar faces in laboratory experiments, today’s systems outperform human capabilities.

Nowadays these systems are among the most widespread applications of Artificial Intelligence (AI). Every day, our laptops, smartphones and tablets greet us by name as they recognise our facial features, but at the same time, the uses of this technology have set off alarm bells over invasion of privacy concerns. In China, the world leader in facial recognition systems, the introduction of this technology associated with surveillance cameras to identify even pedestrians has been viewed by the West as another step towards the Big Brother dystopia, the eye of the all-watching state, as George Orwell portrayed in 1984.

In recent years, however, the use of the face in AI algorithms has gone far beyond mere identification to enter the realm of recreation. This is beginning to tear down the basic premise of the non-transferable nature of our facial features, the idea that, wherever our face is, that’s where we necessarily are.

Facial expressions recreation

In 2016 and 2017, the power of certain algorithms to modify videos of a person’s face was revealed, so that one person’s facial expressions could be transplanted onto another person or the movement of their lips modified to make them say something they never said in front of a camera. A famous example used an audio speech by former US President Barack Obama that was adapted to a video in which he originally delivered a different speech. At the same time, a controversy arose over so-called deepfakes, virtual transformations that some amateur programmers began using to transplant the faces of Hollywood actresses onto performers in pornographic videos.

But while these deepfakes needed to use a large bank of images of the original model to be able to recreate their facial expressions, now just a single portrait is enough. Last May, researchers from the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology and the Samsung AI Center, both in Moscow, publicised a new system that manages to give movement to a face from a few snapshots or even a single one. To demonstrate the power of their algorithm, researchers have published a video in which they create talking busts from a single image of Marilyn Monroe, Salvador Dali and Albert Einstein, and even give life to Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

As Egor Zakharov, the first signatory of the study, explains in a commentary on the video, the aim of these systems is to progress in the creation of photorealistic avatars to facilitate telepresence and communication in augmented and virtual reality. For Zakharov, the “several positive effects” of these technologies include “a reduction in long-distance travel and short-distance commute” and to “democratize education, and improve the quality of life for people with disabilities,” as well as to “distribute jobs more fairly and uniformly around the world” and “better connect relatives and friends separated by distance.”

Video in which talking busts are created from a single image of Marilyn Monroe, Albert Einstein, or Mona Lisa.

These may seem like extremely idealistic goals, but naturally Zakharov also recognises the potential of his technology to create deepfakes for not so noble purposes. The researcher points out that any new tool capable of democratising the creation of special effects has had undesirable consequences, but that the net balance is positive thanks to the development of resources that help to tackle these malicious uses. “Our belief is supported by the ongoing development of tools for fake video detection and face spoof detection alongside the ongoing shift for privacy and data security in major IT companies,” says Zakharov.

Recreate a face with the voice

Equally astonishing, but perhaps more disturbing, is the fact that it no longer takes a single image of a person to recreate their face—just the voice is enough. In 2014, researcher Rita Singh, from Carnegie Mellon University (USA), received a request from the US Coast Guard to identify a prankster who had been making hoax distress calls. Singh has created a system, based on antagonistic generative network (GAN) algorithms, that enables an approximation to be obtained of the physique of a person only from their voice: “Audio can us give a facial sketch of a speaker, as well as their height, weight, race, age and level of intoxication,” Singh told the World Economic Forum. “The results show that our model is able to generate faces that match several biometric characteristics of the speaker, and results in matching accuracies that are much better than chance,” Singh and her collaborators wrote in their study.

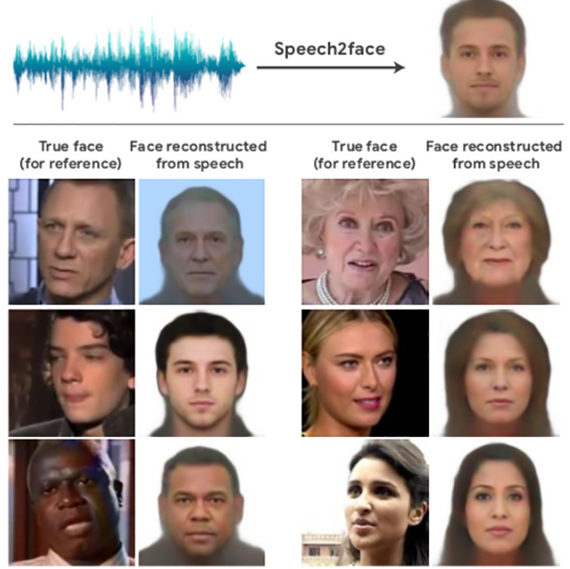

Recently, another team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology introduced the Speech2Face neural network, which is able to build a face from a voice after it has been trained with millions of YouTube videos and other sources. “We have demonstrated that our method can predict plausible faces with the facial attributes consistent with those of real images,” the researchers write in their study. The results are not perfect; the authors themselves make it clear that their system produces average faces, and not images of specific people. But considering that the only source is a brief audio clip, we should all get used to the idea that even our own face is no longer safe with us.

Comments on this publication