It took three centuries after his death for historians to do justice to this multifaceted genius, whom they have begun to call “the English Leonardo da Vinci”. But much is still unknown about Robert Hooke, of whom today not even a portrait has been preserved despite his having been a star of the first golden age of science. His public image has been that of a jealous and vain person, who appropriated the discoveries of others. And both are due to his bitter disputes with Isaac Newton, who is said to have made great efforts to extirpate the achievements of his late arch-rival Hooke when he became president of the Royal Society.

The life of Robert Hooke (July 28, 1635 – March 3, 1703) is the classic tale of a self-made man who went from humble origins in the middle of the English Channel to rubbing shoulders with 17th-century London society. The son of an Anglican curate from the Isle of Wight, his father died when Hooke was 13 and he was left with an inheritance of 40 pounds. But that sum and his artistic skills were enough to allow young Hooke, by making the most of apprenticeships and scholarships, to get himself off that island and enrolled first in Westminster School in London and then the University of Oxford.

It was there that Robert Hooke was finally able to develop his passion for science and enter the circle of great scientists such as Robert Boyle, who adopted him as his assistant between 1655 and 1662. The prestige as an experimenter he gained in those years would serve him well, and he was unanimously granted the position of “curator of experiments” in the newly founded Royal Society of London in 1661, which made him the first paid scientific researcher in England. By that time he had already proposed the famous law of elasticity that bears his name and with which many school children today begin their study of physics.

One of the best experimental scientists

From that position in one of the oldest scientific academies in the world, which he held for the rest of his life, Robert Hooke developed his enormous research output, for which today he is recognized as one of the most important experimental scientists of all time. Hooke’s main task at the Royal Society was to experimentally demonstrate scientific ideas, either by his own methods or by following the ideas sent to him by members of that prestigious society.

There is some evidence that he took advantage of his position to appropriate some of those ideas as his own, which gave rise to his tarnished reputation. Be that as it may, at that time of rapidly expanding scientific knowledge (in which there were always several researchers working on the same ideas) he exhibited plenty of evidence of ingenuity and experimental skills. And both that and his capacity for hard work allowed him to stand out as an expert in an amazing number of specialties: biology, medicine, various fields of physics, engineering, horology (the science of measuring time), microscopy, navigation, astronomy and architecture.

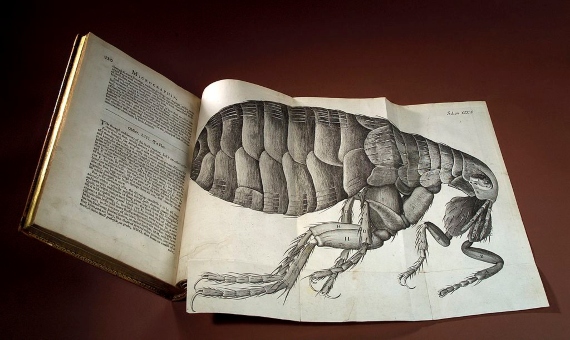

He was the first to build a new type of telescope, the Gregorian telescope, with which he was able to observe that Mars and Jupiter rotated on their axes. He also promoted the scientific use of microscopes, with the iconic illustrations of his book Micrographia (1665), initiating an art perfected by new experts such as Anton van Leeuwenhoek. He is also recognised as one of the first to suggest the idea of biological evolution and also proposed that light was formed by waves, which led to his first contact with Isaac Newton, who in 1670 developed his own theory of colour and argued that light was made up of particles. The criticism he received from Hooke offended him so much that Newton decided to withdraw from that public debate.

Thus Hooke was an authority, and not only in the field of science. After the great fire that devastated London in 1666, he was put in charge of surveying the city for its reconstruction, proposing a modern grid redevelopment. He was also the architect of many new buildings, contributed to the design of others such as the Royal Greenwich Observatory and conceived the method used to build the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

Newton’s great rival

Hooke was at the zenith of his career in 1679 when he began an intense correspondence with Newton about gravitation, an idea that Hooke had already taken on a few years earlier. The great confrontation between the two men occurred when in 1686 Newton published the first volume of his Principia and Hooke affirmed that it was he who had given him the notion that led him to the law of universal gravitation. Hooke demanded credit as the author of the idea and Newton denied it. The most he came to recognise is that those letters with Hooke had rekindled his interest in astronomy, but had not brought him anything new. Many science histories have tried to insert into their quarrel Newton’s famous sentence penned to Hooke in a letter: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” which they consider a dig at Hooke, who was supposed to have been of rather short stature. But the truth is that this letter is earlier, from February 5, 1675, at a time when the relationship between the two English geniuses was still cordial.

There is no certainty about Robert Hooke’s appearance and stature, not least because no portrait of him has been preserved. Historically, this lack is attributed to Newton’s efforts to erase the figure of his great rival. What is certain is that this rivalry continued until the death of Hooke in 1703, upon which the last obstacle to Newton’s appointment as president of the Royal Society on November 30 of that same year disappeared. Newton then fulfilled his promise not to publish his corpuscular theory of light (which had provoked the first quarrel between them) until Hooke had died: he did so a year later, in the book Opticks (1704).

According to scientific legend, Newton also sent for the only portrait of Hooke and ordered it destroyed; another version states that he left it intentionally forgotten when the Royal Society moved to another building. However, Robert Hooke’s most recent biographer and scholar of his figure, Allan Chapman, rejects these stories as pure myths. Chapman and other historians have made a great effort in recent years to once again dignify this great genius of science. In 2003, painter Rita Greer embarked on historical research to produce a portrait of Hooke faithful to the two remaining written descriptions of him. His public image thus restored, that tribute portrait by Greer (which heads this text) has been used to illustrate numerous articles and documentaries, which finally cast Hooke in a fairer light in the history of science.

Comments on this publication