During the COVID-19 pandemic, a legitimate question arose as to whether this could be a laboratory-modified coronavirus. Although there is no proof of this and all the evidence points to a natural origin, this type of research does exist: it is known as gain of function (GoF). The aim of these experiments is not to create biological weapons, but to study the behaviour of viruses and identify possible countermeasures. But it is controversial: is it wise to make a virus more aggressive? Should such research be banned?

The concept of GoF comes from nature, and it is not just about viruses. During evolution, certain genes can mutate in a way that enhances their function. Sometimes this can be beneficial, sometimes not; the gain of function of a gene is responsible for an autoimmune reaction that causes lupus. In the laboratory, GoF experiments can lead to more resistant plant crops, cancer immunotherapies or micro-organisms that produce antibiotics more efficiently.

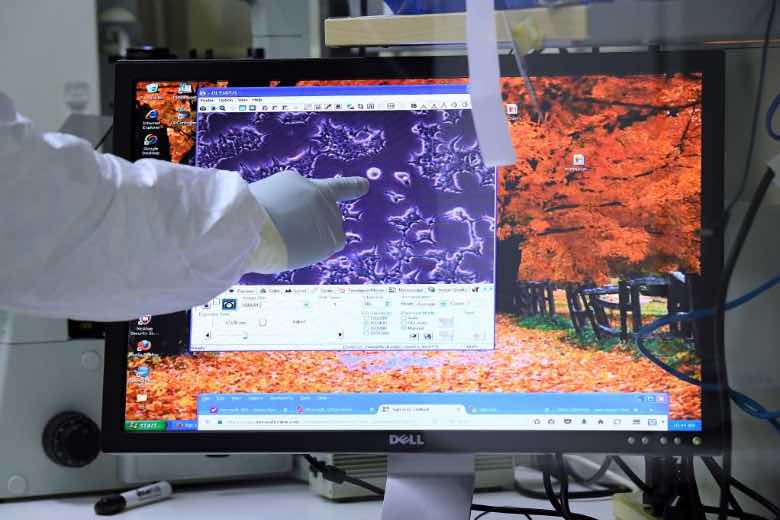

In the case of viruses, the reconstruction in 2005 of the virus that caused the great influenza pandemic of 1918 made it possible, through GoF experiments, to better understand its pathogenic mechanisms and possible future adaptations. Concerns about these experiments gained momentum after 2012, when the dangerous avian influenza virus was successfully transmitted through the air between laboratory ferrets (in these cases there was no genetic modification, but forced adaptation of the virus).

There were growing calls in the scientific community for a debate to weigh the potential risks and benefits of GoF research. The European Union considered that existing legislation was sufficient to regulate the field, while the US imposed a moratorium in 2014 on funding such studies. This was lifted in 2017 and replaced by a special review process. During the recent pandemic, the media reignited the debate, sometimes for no real reason, as when the US was falsely accused of funding GoF experiments with coronaviruses in China.

Necessity versus risks

While obtaining more dangerous viral variants can be risky, many experts argue that such experiments “can help scientists anticipate the changes viruses may undergo in nature by understanding what specific characteristics allow them to transmit between people and infect them,” which is particularly important in the face of current threats such as avian influenza. They argue that biosecurity measures minimise the risk and that bans hold back scientific progress and the ability to save lives.

Pro-ban scientists, on the other hand, argue that the risk is unacceptable, given that pathogens have leaked out of laboratories in the past, and that the benefits of such research are minor. Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch wrote: “While there are indisputably certain questions that can be answered only by gain-of-function experiments in highly pathogenic strains, these questions are narrow and unlikely to meaningfully advance public health goals such as vaccine production and pandemic prediction.” In short, the debate continues with no definitive answer.

Comments on this publication