There are numerous historical figures whose contributions and accomplishments deserve recognition, yet who remain largely unknown to the general public. Then there is Ramón María Termeyer, an 18th century Spanish Jesuit and amateur scientist who is so forgotten today that the dates of his birth and death and the details of his life are even hard to find. But while it is a worn-out cliché to say that someone was ahead of his time, in this case it is an apt description of a man who was one of the pioneers in obtaining and exploiting a material that scientists and engineers are still investigating today as one of the great promises of the future: spider silk. The book Linneo en España — Homenaje a Linneo en su segundo centenario 1707-1907, published in 1907 by the Aragonese Society of Natural Sciences, said of the naturalist Termeyer: “He was extremely deserving and almost forgotten.” Termeyer’s obsession with mastering the power of spiders and his unwavering dedication to this work have earned him a rightful place in history as a visionary Spider-Man of his time.

Fortunately, we know more details about the intense scientific work that occupied much of his life, from America to Italy. During the 1760s, in the River Plate region of South America, he experimented with electric eels, or knifefish; electricity was the great scientific mystery in vogue in the 18th century, with the experiments of Benjamin Franklin, Luigi Galvani and his wife Lucia Galeazzi, Alessandro Volta and others. Termeyer’s interest was not exceptional; before him, other missionaries in South America, including several Jesuits, as well as explorers and naturalists, had been interested in studying the properties of these eels.

From electric eels to new insect species

Years later, in Italy, Termeyer published the results of his studies, which were later collected in the five volumes of his Opuscoli scientifici d’entomologia, di fisica e d’agricoltura, published between 1807 and 1810. He covered a wide range of subjects, mainly insects, spiders and their silk, which he compared to that of silkworms, but also the natural history of South America, yerba mate, antidotes to viper venom and how to keep eggs fresh during long journeys.

But in particular, and unfortunately, his conclusions about electric eels were completely erroneous. Termeyer wrongly proposed that the phenomenon of these creatures and other electric fish was due to a third fluid different from those encountered by Galvani and Volta, a “gymnotic fluid”; in other words, he claimed that electric eels were not electric. In any case, his work in this field was ignored by his contemporaries. He also had no luck with the new species of insects he described.

The first known apparatus for extracting silk

Despite these failures, the success for which he deserves to be remembered was a remarkable achievement. Termeyer had begun to familiarise himself with spider silk during his time in South America, but it was in Faenza and later in Milan that he devoted himself intensely to these studies. He was not the first to undertake this endeavour: at the beginning of the 18th century, the Frenchmen René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur and François Xavier Bon de Saint Hilaire had tried to find an alternative to silk from silkworms. To achieve this, they followed a similar process to that used for silkworms, carefully boiling the cocoons that encased the spider eggs; however, their technique met with little success. Although both men succeeded in obtaining spider silk, they only recovered insufficient quantities, and the problem with large-scale spider breeding was that they ate each other. Réaumur concluded that spider silk was of no commercial interest.

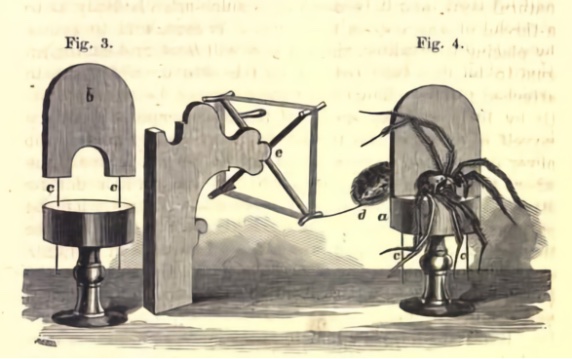

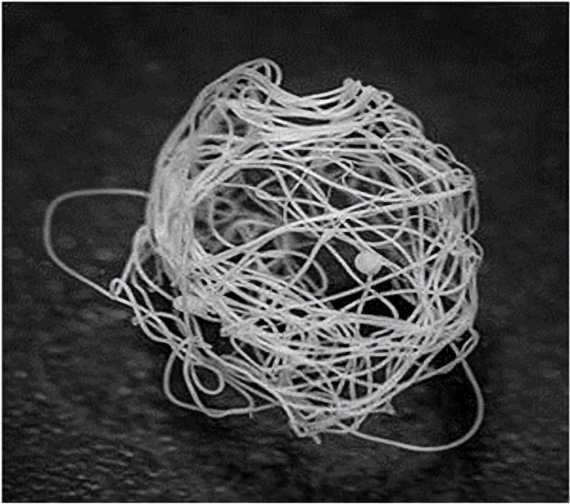

Termeyer was familiar with the work of both men, but he did not accept their conclusions. In his house in Milan, which he transformed into a museum full of scientific instruments and with a large collection of insects, he managed to breed thousands of live spiders, which he kept suspended from separate canes so that they would not devour one another. He devised a way of extracting the silk directly from their bodies, using a contraption he invented consisting of a cork and a small metal yoke that allowed him to immobilise the animal by separating its legs from its abdomen, to prevent it from cutting the silk. Termeyer kept piles of rotting meat to breed a steady supply of flies, which he fed to his spiders. When an insect was brought near a spider, it would begin to secrete silk, which Termeyer would then wind around a spool. The silk he collected, he wrote, was shinier and more beautiful than that of the silkworm, so much so that it resembled polished metal or a mirror.

A late and still insufficient rediscovery

According to one version of the story, the silk he harvested was given to his relative and student Lucrezia Rasponi, who knitted gloves and stockings with it. Termeyer is said to gifted these garments to some of the most prominent figures of his time, such as Charles III of Spain, Catherine the Great of Russia, the King of Naples and Archduke Ferdinand of Austria. He supposedly even gave them to Napoleon, his wife Josephine and his daughter-in-law Princess Augusta of Bavaria, despite the fact that Termeyer’s own house had been razed to the ground during the Napoleonic invasion of Italy in 1796. But the book of the Aragonese Society of Natural Sciences quoted at the beginning tells another version of the story: Termeyer only made one pair of stockings, which he sent to the King of Spain in 1788, rejecting offers of purchase from other noble personages. Termeyer wanted Charles III to acquire his museum, and perhaps this was a way of intriguing the monarch and making himself known.

In any case, there is no record of what became of these gifts or whether their recipients appreciated them, but Termeyer’s work did eventually come to be recognised, half a century later. Sometime between 1810 and 1820, he described his studies with spider silk in a pamphlet published in Milan, the only known copy of which somehow passed from hand to hand until it was discovered in a New York library in 1866 by the US Army surgeon Burt Green Wilder. Three years earlier, Wilder had begun work on a device for obtaining spider silk. Reading Termeyer’s text, whose English translation he published, Wilder was amazed at how much the instrument he had designed and patented resembled the one invented earlier by the Spanish Jesuit. And he was also particularly struck by how both the work and its author had been overlooked and neglected for decades.

Despite Wilder’s rediscovery, Termeyer remains largely forgotten today. His name is even omitted from some of the historical reviews of spider silk production, even though his apparatus was the first that actually worked. Today, scientists continue to pursue the goal that obsessed the 18th century Spider-Man.

Comments on this publication