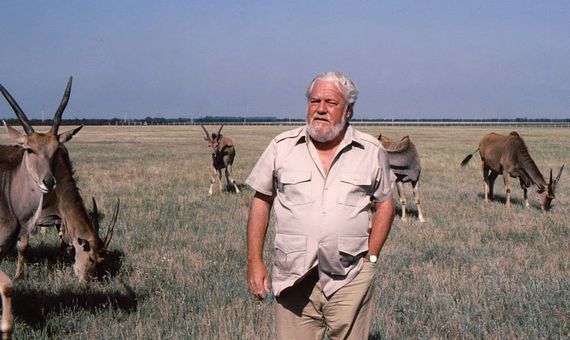

The first word he uttered in his life was not “mum” or “dad”, but “zoo”, as he told journalist Esteban Sánchez-Ocaña in 1984 in an interview for Spanish Television (TVE). If what his mother Louisa told him was true, few lives have had such a clearly defined object from the start as that of Gerald Durrell (7 January 1925 – 30 January 1995). He wanted his own zoo and he eventually got one, where he undertook valuable work in breeding endangered species, a model for many other conservation institutions.

But Durrell was something more: he was his own person. Through his loosely autobiographical novels, especially the trilogy about his childhood years on the Greek island of Corfu, he has delighted millions of readers with his fresh, humorous and tender prose. And few books like his have spread the love of animals that was his life’s passion. Although, as he also confessed in that interview, his favourite animal was his wife.

Greece and his family as an inspiration

Born in the Indian city of Jamshedpur under British rule, his engineer father died prematurely, leaving his widow and four children in an untenable financial position in Britain at the time. The family then opted for a radical departure, emigrating in search of a cheaper place, and Corfu was the destination. There, the 10-year-old Gerry was able to give free rein to his vocation as a naturalist under the teachings of the physician and scientist Theodore Stephanides, who befriended the family. While Gerald filled the house with animals, his mother tried to provide for her children with limited resources and in a country whose language none of them spoke.

All in all, it was a happy four years until 1939, when the outbreak of World War II, with Greece under the domination of the Axis powers, forced the Durrells to leave Corfu. Years later, Gerald would capture those experiences in My Family and Other Animals (1956), Bugs and Other Relatives (1969) and The Garden of the Gods (1978). The books contain a certain degree of fiction; for example, his brother Lawrence—who was to become one of the most celebrated British authors of the 20th century, notably with his tetralogy The Alexandria Quartet—did not live with the rest of the family, but in another house with his wife Nancy, who is never mentioned. But Gerald himself assured us that most of what is narrated is true. The books have been made into films and television series several times, with notable success.

Writing was an occupation to which Durrell devoted much of his life, producing a total of nearly 40 books, most of them autobiographical, along with several works for children. And yet he confessed that he took no pleasure in writing and that he did it only to earn a living and to work his way towards what was to be his life’s dedication, as his lack of education did not afford him many employment opportunities. On his return to England he worked in a pet shop, on a farm and finally in a zoo, before managing to finance his first animal expedition with his father’s inheritance when he turned 21.

A commitment to zoos as wildlife conservation centers

Over the years Durrell undertook numerous trips around the world to capture animals which he sold to various zoos, while also making his first documentary films. However, he was disappointed that zoos devoted little attention to the recovery of endangered animals, which he believed should be their primary work. So, when his situation and the profits from My Family and Other Animals allowed him to do so, he realised what had always been his dream, to set up his own zoo. He did so on the island of Jersey, a British dependency off the French coast in the English Channel. The park opened in 1959, but four years later expanded into a more ambitious endeavour, the Jersey Wildlife Preservation Trust (now the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, DWCT).

Under its emblem of the dodo as an icon of extinction, for six decades the DWCT has bred countless mammals, reptiles and birds in captivity to prevent their disappearance; species such as the Mauritius pink pigeon, the Mauritius kestrel, the Madagascan ploughshare tortoise and the Majorcan midwife toad, among many others, would probably have disappeared from the face of the Earth had it not been for Durrell’s work. The Trust has also carried out intensive species recovery work around the world in cooperation with local communities, organisations and governments, training foreign students and professionals at DWCT facilities and then working with them in situ.

Throughout this time, Durrell defended the value of zoos for the regeneration of endangered species in the face of a growing movement opposed to zoos. In 1985, he published in Nature a review of a new book, in which he took the opportunity to argue that “zoos as a whole are under attack from a vociferous group of so-called animal lovers, ill-informed for the most part and ignorant of the real function and value of a well-run zoological collection,” he wrote. He acknowledged that not all zoos assumed this role, but appreciated that many had moved from being “mere consumers of wild creatures” to being their “champions and helpers.” Durrell stressed one of his most repeated arguments: if facilities are designed with animals rather than humans in mind, captivity is not a prison for them as long as they have a space similar to their territory in the wild, and that dwindling nature reserves are also becoming large zoos, and not always well managed ones.

With his health undermined by the consequences of his expeditions, Durrell died of septicaemia in 1995. His ashes now lie in the grounds of the DWCT in Jersey. After his death, his widow Lee has continued his work, although the organisation has faced financial difficulties that have threatened its survival. In 2016, in an interview with The Guardian, Lee lamented that Gerald’s books are not as widely read today as they once were. And yet that interview was prompted by the premiere of a new television version of the Corfu trilogy, the series The Durrells, which was a great success with critics and viewers. No doubt his legacy remains as vivid today as the species he saved from extinction. This goes to show that, if Durrell was in any way inept, it was as a prophet, when he told TVE in 1984: “I don’t consider myself to be a real writer like my brother. In 50 years’ time, people will still be reading his books, not mine.”

Comments on this publication