The awarding in 2020 of the first ever Nobel Prize for science to a team made up only of women—Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna, winners of the Chemistry Prize for their creation of the genetic tool CRISPR—reminds us that in the 21st century, milestones are still being reached for female science. And this makes the few examples of the women pioneers who once chose science as their vocation even more astonishing, especially when this meant giving up even their own name for a male pseudonym so that their work could be acknowledged. This was the case for an exceptional and not very celebrated figure, the mathematician María Andresa Casamayor de La Coma. But fortunately for us, the only 18th century Spanish woman of science who left behind published work, knew how to resort to a clever trick to ensure that the authorship of her work was solidly established.

So little is known about Casamayor (30 November 1720 – 23 October 1780) that some brief details of her still obscure biography were only revealed thanks to a documentary filmed in 2019 and an investigation by mathematicians Julio Bernués and Pedro J. Miana, from the University of Zaragoza, the birthplace of this trailblazer. As a result, we know that she grew up in a large family of French origin that was involved in the textile business. Her epoch was favourable for science and learning, being at the height of the Enlightenment, although to a great extent these were off-limits to women.

A mathematical anagram by pseudonym

Elsewhere in Europe, the talents of Caroline Herschel, Maria Gaetana Agnesi and Émilie du Châtelet, among other women scientists, shone through, but often their contributions were either virtually ignored in their time or obscured under the name of their male collaborators or patrons. These men, if their position allowed them, could devote their lives to science, while the women had to combine their scientific passion with the role of wife and mother that society imposed on them, and which often offered only one alternative: to take the veil.

Casamayor did not choose one option or the other; she remained single and did not enter the Church, although it did play a significant role in her life, as was common at the time. It is assumed that she received a religious education at home, as befitted the position of her family, a privilege in times when illiteracy was almost the norm, especially among women. And although the details of her childhood are not known, it is clear that she soon excelled at mathematics, as at the age of 17 she published her first and only work that saw the light of day.

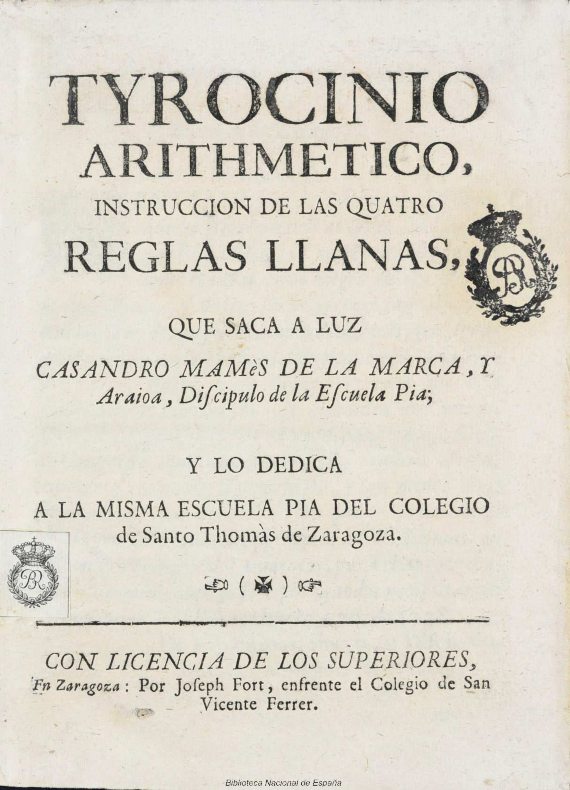

Tyrocinio Arithmetico, Instrucción de las quatro reglas llanas, published in March 1738, was a book designed to facilitate the learning of basic arithmetic: addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. For its publication, Casamayor had the ecclesiastical sponsorship of the priest Juan Francisco de Jesús, professor of mathematics, and the friar Pedro Martínez. But likely bound by the conventions of the time, the young mathematician signed her work with a male name, although she did so in a way that surreptitiously preserved her identity; the pseudonym chosen by the author, Casandro Mamés de La Marca y Araioa, is a clue worthy of her mathematical vocation, an elaborate anagram of her full name. Under this ploy, Tyrocinio Arithmetico became the first science book published by a woman in Spain. To the immense value of this achievement we must add the fact that only one known copy has survived to the present day, and it is kept in the National Library of Spain.

A prematurely truncated mathematical career

Later, Casamayor wrote a second work under the title El para si solo, a longer book on advanced arithmetic. There is no record of the reasons why this manuscript, which has now disappeared, was never published, although misfortune led to the author losing her support in the years following the publication of Tyrocinio, when her father and Friar Martinez died and the mathematician De Jesus moved to Valencia. Nor is she known to have had interactions with other mathematicians of her time, not even in her own city.

But if today we don’t know in detail the reasons why a promising mathematical career was prematurely cut short, beyond the difficult context of the time, we must laud Casamayor for having dedicated the rest of her life to a quieter, but even more crucial task: the education of girls. Presumably, in the long years in which this illustrious pioneer worked as a female schoolteacher, until her death shortly before turning 60, Tyrocinio served to break the chains of illiteracy for a multitude of girls. And this is the first minimum requirement, to be able to touch with one’s fingers the glass ceiling that still needs to be broken.

Comments on this publication