At one time it was known by the macabre name of “the strangling angel of children.” Diphtheria used to claim hundreds of thousands of lives each year, and there was no treatment for this bacterial disease that closed off the airway with a mass of dead tissue, until German doctor Emil von Behring and his collaborators finally found a cure. But this story had other non-human protagonists: horses. Even today, along with antibiotics, the antitoxin produced in these animals remains the standard treatment for diphtheria, a traditional method that may soon be abandoned thanks to the progress of biotechnology.

Emil von Behring (15 March 1854 – 31 March 1917) came to diphtheria following the trail blazed by the pioneer of antiseptic medicine, British surgeon Joseph Lister. The German began his career by experimenting with antiseptic substances, but at the institute of the famous bacteriologist Robert Koch he was given the opportunity to devote himself to what seemed at the time to be the most promising avenue in the fight against infection: neutralizing bacterial toxins

In 1888, French physician and bacteriologist Émile Roux and his assistant, Alexandre Yersin from Switzerland, working at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, isolated the toxin from the diphtheria bacillus (Corynebacterium diphtheriae), which was partly responsible for the lethal effects of the disease. The finding led to the belief that the toxins were involved in all bacterial infections. This was not true, but it was the case for diphtheria and tetanus. For these cases, Behring and the Japanese Shibasaburo Kitasato managed in 1890 to inject the toxin into laboratory animals and obtain from them a serum that prevented and cured the disease in other animals.

Antitoxins for tetanus

Behring called this healing serum “antitoxin,” and correctly surmised that it was a product from the active immunization of the animal by the toxin, which when injected into another animal protected it from the disease by passive immunity. In 1891, Behring’s collaborator and later rival, Paul Ehrlich, first used the name by which we know the elements present in these antisera today: antibodies.

As bacteriology and immunology historian Derek Linton, author of the award-winning biography Emil von Behring: Infectious Disease, Immunology, Serum Therapy (APS, 2005), explains to OpenMind, “both Behring and Kitasato did discover anti-toxins for diphtheria and tetanus simultaneously while working in adjacent laboratories.” However, the Japanese researcher soon turned to the study of tuberculosis, and “it remained for Behring and his assistants, especially Erich Wernicke, to progress this important discovery and provide proof of concept that antitoxins for tetanus and diphtheria could be used to cure humans.”

Using guinea pigs, rabbits and sheep to produce the serum, in mid-1892 Behring achieved the first successes with human tetanus. Diphtheria would take a little longer. While there is a story circulating that Behring first cured a child with his serum on Christmas Day 1891, according to Linton this never happened. In fact, the first clinical trials with the diphtheria antitoxin began with a few children in late 1892, but it was not until two years later that positive results were obtained in a larger group, using a serum produced by Ehrlich in goats.

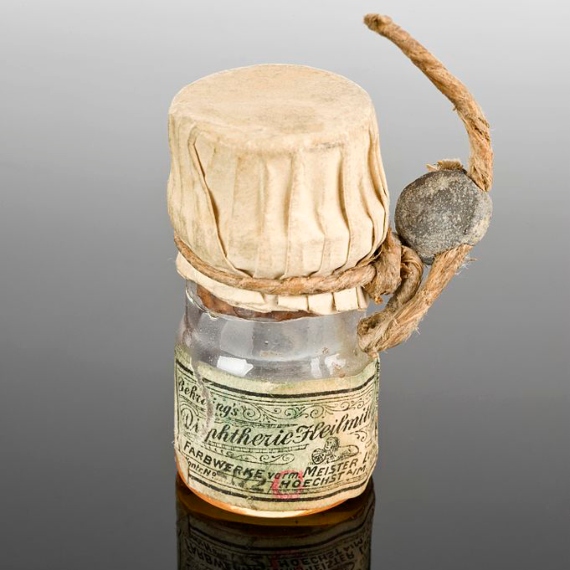

During these trials, 168 of the 220 children treated were cured; the resulting 23.6% mortality rate was less than half the usual outcome in cases of diphtheria. In particular, the serum promised almost certain salvation if administered within the first two days of illness. In August 1894, the Hoechst company, through a contract with Behring and Ehrlich, began marketing the new remedy, which was so spectacularly effective that in 1901 it would earn Behring the first Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. “Behring was also the first to detect and report negative immune reactions to animal generated anti-toxins, notably hypersensitivity, a term he coined,” Linton adds.

Saviours against the scourge of diphtheria

Both the German group and their competitors at the Pasteur Institute and elsewhere began producing their serums in horses, large animals which made it possible to easily obtain greater quantities of antitoxin than from smaller sheep or goats. The stables for the manufacture of antisera began to spread rapidly, and not only in the Old World—as early as the summer of 1894, the chief bacteriologist of the New York City Department of Health, Hermann Biggs, was able to observe for himself how these laboratories proliferated throughout Europe, and he immediately imported the technique. Before the end of the year, 13 horses were already producing diphtheria antitoxin at the College of Veterinary Surgeons in the heart of Manhattan.

In subsequent years, the antitoxin horses became enormously popular with the public as saviours against the scourge of diphtheria. In New York, Biggs would show off the clean stalls of the animals, explaining that they were treated like hospital patients, were usually not harmed by the inoculation, and were well fed and cared for.

However, there was no shortage of failures: in 1901, 13 children died in St. Louis, Missouri, when they received serum from a horse named Jim who was sick with tetanus. This tragedy resulted in the first regulation of biological products in the United States, which would later lead to the creation of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Last January, a study described how genetic technologies are used to obtain antibodies capable of neutralizing the diphtheria toxin, a project funded by an international consortium from the animal welfare organization PETA. And there is at least one other research group pursuing the same goal: producing antitoxin without horses. Fortunately, thanks to vaccination, diphtheria is no longer a big threat. But there is also a downside to this development: the prospects for funding the necessary clinical trials and for a company to invest in the development of these products are not particularly bright, as this is a disease that has almost been forgotten. And yet, closing this chapter in the history of medicine seems like an obligation we have to the four-legged heroes who for over a century kept us safe from the “strangling angel”.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication