On 7 September 1936, the last known thylacine, a female (not a male named Benjamin, as is often published), died in Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. Although reports of sightings of this mythical marsupial continue to this day, and a recent study even suggested that it may have survived into the 1980s, the species officially became extinct on that day. And sadly, it was not the only one to disappear under our care. Writing in the journal Science, researchers from the Zoological Society of London and other institutions have compiled a list of 95 species that have survived in captivity since 1950 after going extinct in the wild. Of these, 11 have already been lost. Here is a look at some of the species that died out before our eyes.

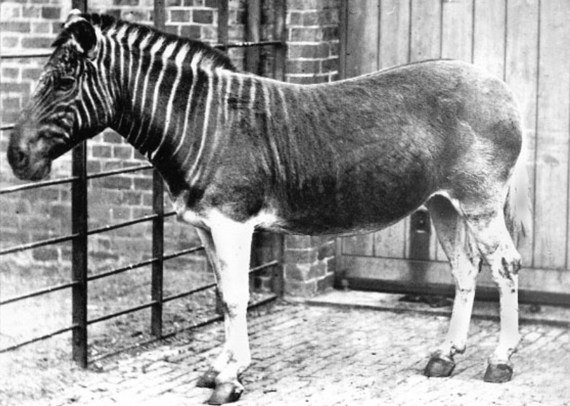

Quagga (Equus quagga quagga)

The most classic case of extinction in captivity is that of the quagga, a subspecies of the common zebra that lived in South Africa. With reddish-brown fur and an unstriped back half, its appearance was very different from other zebras. As in so many other cases, the cause of its extinction was human hunting, in this case to reserve grazing land for livestock. The last specimens in the wild died in 1870, and the last in captivity in 1883 in the Amsterdam Zoo. The quagga is one of the targets of species de-extinction projects.

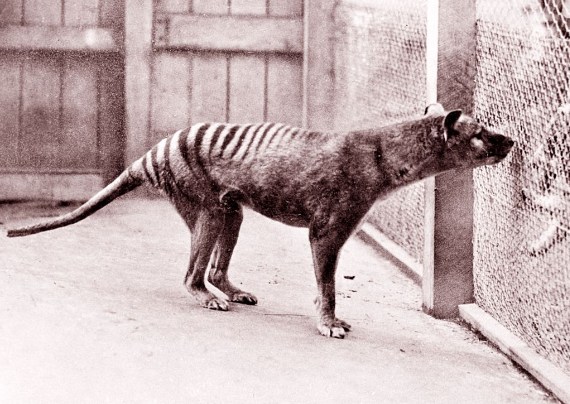

Thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus)

Known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf because of its tiger-like stripes and wolf-like appearance, the thylacine was actually the world’s largest marsupial carnivore. Originally native to Papua New Guinea and Australia, by the time European settlers arrived it was restricted to a sparse population on the island of Tasmania. The thylacine was hunted to extinction in the wild; the last female was given to Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart in 1931. In 1936, 59 days after it was declared a protected species, it died from neglect during a spell of extreme temperatures.

Passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius)

The passenger pigeon is one of the bloodiest cases of extinctions at human hands: its habitat was not some remote part of the planet, but North America. And it was not a rare species; chroniclers of the time recount that its huge flocks darkened the sky with a compact black mass, and that its droppings fell like snow. But it was hunted to extinction in the 19th century. The last known individual, Martha, died of old age on 1 September 1914 in the Cincinnati Zoological Garden. Today she is on display at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington.

Carolina parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis)

The Carolina parakeet was the only member of the parrot family native to the eastern United States. Known since the 16th century, this brightly coloured bird, which formed large, noisy flocks, declined under human pressure until the 19th century, but was prized for eating the seeds of a plant poisonous to livestock. The reason for its rapid decline in the early 20th century is contentious, although it is likely attributable to human causes. The last known wild specimen was killed in Florida in 1904. The last captive specimen, Incas, died on 21 February 1918 in the Cincinnati Zoological Garden, in the same cage as Martha, the last passenger pigeon.

Pinta Island tortoise (Chelonoidis niger abingdonii)

The prize for the most famous “endling” in recent times—”endling” is the term proposed in a 1996-letter to Nature for the last specimen of a species—must surely go to Lonesome George, the last of his subspecies, one of several types of giant tortoise in the Galapagos Islands. He was found in 1971 and brought to the Charles Darwin Research Station, where attempts were made to interbreed him with other subspecies, but without success. He died of natural causes on 24 June 2012, estimated to be over 100 years old. However, hybrids of this subspecies have been found in recent years.

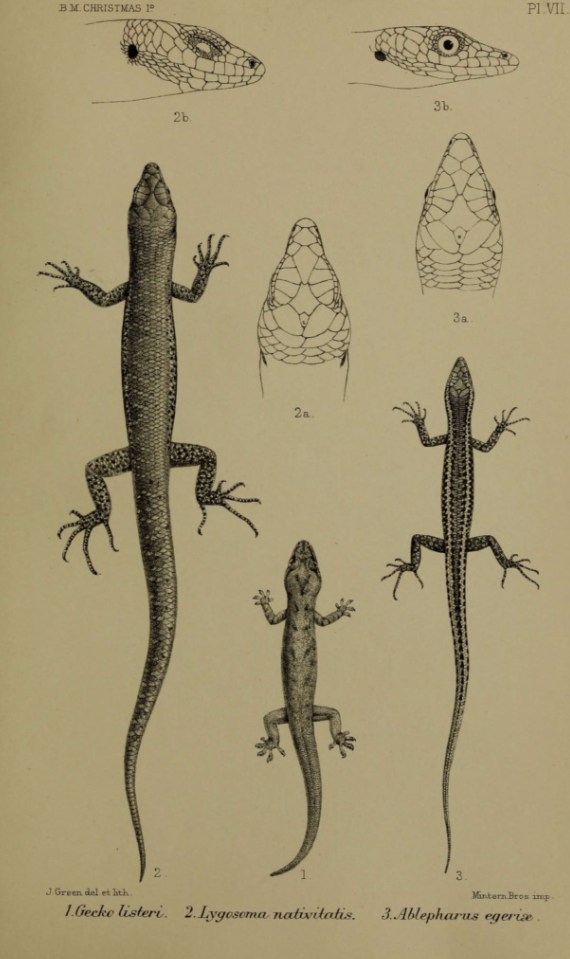

Christmas Island whiptail-skink (Emoia nativitatis)

Gump, the last known specimen of the Christmas Island whiptail- skink, formerly endemic to Australia’s Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean south of Java and Sumatra, died in captivity on 31 May 2014. The 20-centimetre-long brown lizard had been known to science since 1887. It was abundant until the 1980s, but populations plummeted by up to 98% in the 1990s and 2000s for unknown reasons. An exhaustive search was undertaken, but only three females were found. The species was doomed, and all died in captivity.

Po’ouli (Melamprosops phaeosoma)

Even a US island like the Hawaiian island of Maui held undiscovered biological treasures until at least 1973, when a black-headed honeycreeper was found and named po’ouli or poo-uli. By then the bird was already rare, possibly due to disease and predation. In just ten years, the population fell by 90%. Despite conservation efforts, only three individuals were known in 1997. Two of these were last sighted in 2003-4. The last was captured in September 2004, but died in captivity just 78 days later.

Catarina pupfish (Megupsilon aporus)

A small four-centimetre-long fish was discovered in 1961 at the El Potosi spring in the Mexican state of Nuevo León and scientifically described in 1972. During the 1980s and early 1990s, there were fears for its survival because the original pond was drying up due to groundwater extraction, and specimens were collected for captive breeding in Mexico, the USA and Europe. By 1994, it was considered extinct in the wild. Another species found in the same spring is still extant, but the so-called Catarina pupfish proved difficult to keep alive in aquariums. The last specimen, a male, died at the University of California, Berkeley in 2014.

Saint Helena olive (Nesiota elliptica)

It is not only animals that can become extinct under human care—so can plants. One example is the Saint Helena olive, native to the island of the same name in the South Atlantic Ocean. Despite its name, it is unrelated to the true olive tree, but is instead a plant related to the rose bush. It lived in mountain forests of the island, but by the 19th century it was rare due to deforestation and grazing by introduced goats. It was thought to be extinct until 1977, when a single specimen was discovered. The problem was that it proved to be self-incompatible for seed production. The original plant died in 1994, but a cutting produced several seedlings. By 1999, only one had survived, and in 2003 it fell victim to a fungal infection that finally wiped out the plant for good.

Six species of snails

The humble snails (gastropod molluscs) are the group with the most representatives on the list of species that have gone extinct under human care. Aylacostoma stigmaticum, a freshwater species collected from the wild in 1993, was threatened with extinction by the filling of the Yacyretá reservoir on the Paraná River between Argentina and Paraguay. By 1996, it was considered extinct in the wild. The captive specimens died of a disease, possibly viral, in 2011. The other five species, Polynesian land snails of the genus Partula (P. arguta, P. aurantia, P. turgida-clarkei, P. faba and P. labrusca), were wiped out in the wild because of the introduction in the 1980s of the rosy wolfsnail (Euglandina rosea), an invasive carnivorous land snail from the south-eastern part of North America. Faced with extinction, the native species were collected and bred in captivity, but they all eventually died out, the last of them—Captain Cook’s Bean Snail (Partula faba)—in 2016 in Edinburgh Zoo.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication