Experimentation on animals is a sensitive issue. Throughout history, science has relied on animals to perform experiments, sometimes even alive and without anesthesia, using their bodies in the interest of medical advances or simply out of curiosity about the world around us.

Today, however, animal experimentation is rather limited. In the developed world, laws regulating animal testing aim to minimize its occurrence as much as possible and limit the pain that might be caused to animals; regulation is generally restrictive and cases of animal testing limited.

Still, throughout the history of science, there have been animals who, because of how they were used for research purposes, have become authentic legends in popular culture. Some research initiatives that used animal testing caused a lot of debate in their age, debate that rages on today. Other research projects studied animals in fields such as anthropology, psychology, or physics.

Dolly the sheep

History’s most famous sheep was born on July 5, 1996 in Edinburgh. Although she was not the first animal to be cloned — she wasn’t even the first mammal: between the middle of the last century and the time Dolly was cloned, rats, pigs, chickens, and frogs had been cloned — Dolly was the first animal to be cloned from an adult cell, and therefore was genetically identical to the donor.

This scientific experiment received significant media attention and became one of the most famous in history. At the time, it instigated a debate about cloning and genetic engineering and what benefits it could provide humans. Although the technique used to clone Dolly (SCNT or somatic cell nuclear transfer) has seen few advances in recent years, there are still some potential applications such as the resurrection of extinct species. Scientists have already attempted to “resurrect” the Pyrenean ibex and could even go so far to bring the mammoth back to life. Another application of SCNT is the cultivation of tissues and organs.

Dolly died from a lung condition complication in February 2003. Her body has been preserved and is on display at the Royal Museum of Scotland.

Laika

Like Dolly, Laika was not the first pioneer in her “field.” She may not have been the first animal in space, but she was the first to orbit Earth. By the middle of the space race, the Soviet Union had already sent 12 other dogs into space, but always on suborbital flights. On November 3, 1957, Laika took off onboard Sputnik II. Sadly, she never returned.

Her death shocked the world, and she became a sort of Cold War martyr. The controversy was fueled by those who believed it exceeded ethical boundaries to send live animals on “suicide missions” (the mission that took Laika to space was never designed to return to Earth). The resulting protests were far from massive. At the time there was not the awareness about animal testing or experimentation that there is today. Also the Soviet authorities limited freedom of expression. Still, criticism was lodged from within the scientific community and even the scientists who were involved in the mission later regretted Laika’s death.

The Soviet Union did not send any more animals to space without a plan for their return. This was the case for the Belka and Estrelka, dogs that traveled aboard Sputnik V and returned to Earth safe and sound.

Pavlov’s dogs

Pavlov’s dogs were other famous canines. At the end of the 19th century, the Russian doctor, Ivan Pavlov, conducted his famous experiments that proved reflexes could be conditioned (now known as “classical conditioning”). He used various stray dogs in his research.

Pavlov observed that these animals salivated when they saw food, a reaction produced by a direct stimulus. Later, he noticed that the dogs also salivated simply at the sight of the assistant who normally brought their food. His proposition was to condition the natural salivation reflex by introducing a neutral stimulus. Prior to feeding the dogs, Pavlov put on a metronome (not a bell, as popularly believed); after various repetitions, the dogs salivated by association, merely from hearing the metronome, without having to have food brought to them.

Pavlov conducted other behavioral psychology and physiology experiments on his dogs, for which he won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1904. By today’s standards, his approach could be considered controversial, because surgery was performed on the dogs in order to collect their saliva and study their digestive systems. Given the era in which he worked, Pavlov was a pioneer in the ethical treatment of animals: he was opposed to vivisection (the subjection of animals to cutting operations), and anesthesia was always used to avoid unnecessary pain.

Schrödinger’s cat

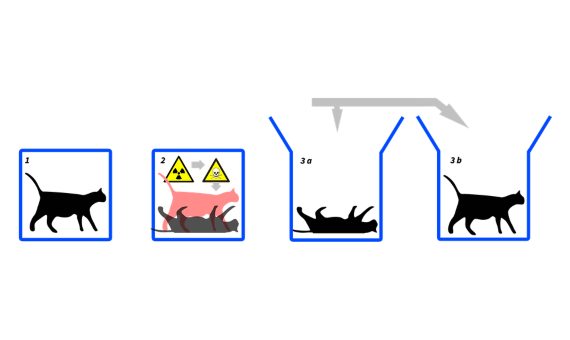

The famous paradox of Schrödinger’s cat is really a theoretical construction; as such, the cat never really existed, or at least there’s no proof that it did. But the Austrian physicist, Erwin Schrödinger, used this animal in the 1930s as a way to explain wave-particle duality.

Because the concepts related to quantum mechanics are so difficult to explain and understand, Schrödinger proposed the following experiment: a closed chamber containing a cat and a flask of poison, which will be shattered if a particle with a 50 percent probability of disintegrating within an estimated time frame, disintegrates. Therefore, once that time is up, there is a 50 percent probability that the cat is alive and a 50 percent probability that it is dead.

If we open the container, we would discover the cat is alive or dead, but the principles of quantum mechanics posit that while the box is closed, there is a superposition of states in which the cat is alive and dead at the same time. Probability can determine what the possibility is of the cat being alive or dead, but it is the act of opening the box to check on the state that forces nature to rush towards one reality or the other.

This hypothetical experiment attempts to explain how some particles can be in two states at the same time, which is known as an quantum superposition, a property that macroscopic systems (like cats) do not have. But behind this paradox lies the explanation of even more complex concepts like the existence of multiple universes.

Nim Chimpsky

Noam Chomsky is undeniably one of the most notable linguists of the modern age. From the middle of the last century, this researcher revolutionized the study of language by maintaining that the capacity of language is exclusive to human beings. He meant that although other living beings communicate in different ways, only humans are capable of establishing a universal grammar and producing and understanding infinite sequences of signs, using specific rules of grammar that apply to a language.

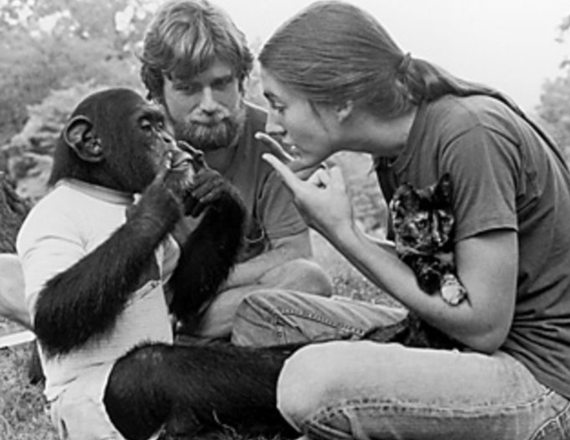

However, a group of scientists proposed to disprove this theory toward the end of the 1960s. They attempted to teach American Sign Language (ASL) to chimpanzees. To do this they tried to raise a number of chimpanzees as if they were human children. A chimpanzee named Washoe managed to learn 350 signs but did not prove himself capable to express himself in a language.

The researcher, Herbert Terrace, wanted to go further and prove that apes were able to use signs to recognize and produce conversations. Terrace then raised Nim Chimpsky (whose name was given as a joke and play on words with the name of the famous linguist.). The history of Project Nim, in addition to being a resounding failure, was tarnished by the methods used to rear and train Nim. Nim learned signs, but he used them pragmatically and not to communicate. Meaning, the chimpanzee did not learn to express himself with language, rather he mimicked gestures for a specific result, something any animal can do using the repetitive method. The experiment ended up providing more support for Chomsky’s theory.

Bonus track: lab rats and fruit flies

Animals continue to be essential for scientific research. Seventy-six percent of the Nobel Prize winners in medicine since 1901 have relied on animal experimentation. Even though all kinds of animals were used in the name of science in the past (with little or no control), between 95 and 97 percent of animals used for this purpose today consist of rats, mice, fish, and birds; with mice and rats making up the majority.

We share 95 percent of our genes with these rodents, which makes them key in genetic research and studies of the nervous system. As a result, today we have anesthesia, penicillin (animals were not used in its discovery, but were used to test how it combats infection), insulin, and many modern-day vaccines.

Another species that is often used in research is the fruit fly, especially in genetic research, because it has the ideal qualities: it is small, therefore easy to maintain and manipulate; its genome is known and is largely similar to the human genome; and it reproduces very quickly, so various generations can be studied in a short period of time. Studies using these insects have resulted in researchers winning five Nobel prizes: from how genes exposed to radiation mutate to the discovery of circadian rhythms.

In scientific research today, the use of animal experimentation is much reduced, extremely controlled, focused on avoiding pain, and tends to look for alternatives. Work has already begun to find ways to support research without animal testing, so that in vitro organisms or even computational models can be used in lieu of live animals. But, for the time being, no artificial system can duplicate the complexity of a living organism.

Comments on this publication