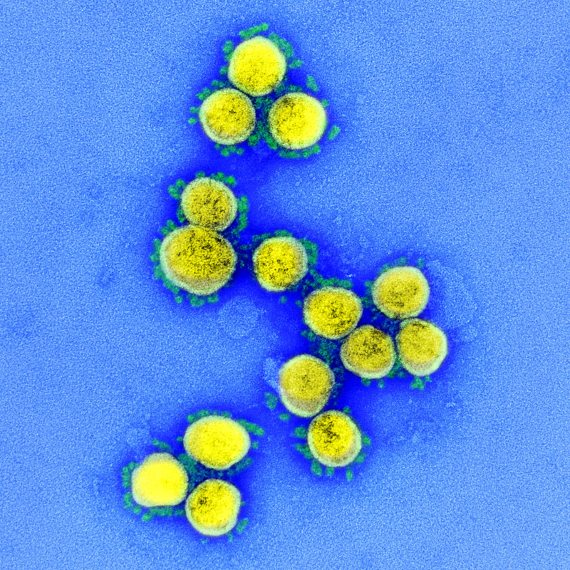

In the spring of 2020, when much of humanity was retreating into their homes to cope with the COVID-19 pandemic, a crucial question was on many scientists’ minds: would the coronavirus give us a break in the summer, mimicking other respiratory infections such as the flu or common colds? The potential seasonality has been one of the great unknowns surrounding the new virus, and now that summer has ended in the northern hemisphere, the truth is that there are still no conclusive answers. But merely knowing that the epidemic has not vanished on its own during the warm months is not enough. Determining the seasonal influence on the behaviour of SARS-CoV-2 is still essential if we are to prepare not only for the coming winter, but also for the years to come.

The seasonality of certain diseases is so obvious that even 2,500 years ago the father of medicine, Hippocrates, was already calling those illnesses linked to one season of the year “epidemics”. Nevertheless, after two and a half millennia, we still haven’t nailed down every last detail as to why the flu attacks us in winter. Traditionally, social explanations were given; the cold weather leads us to take refuge in closed, heated spaces where we share the same air. In the 1960s, cultures of common cold rhinoviruses revealed a preference by these pathogens for cool temperatures in the nostrils.

More recently, studies have shown that the influenza virus increases its stability and infectivity at low temperatures and humidities, the conditions of winter when cold temperatures dry the air by condensing water vapor. Part of the explanation lies in the virus’ lipid envelope, which in cold weather forms a protective coating with the consistency of a gel, which liquefies with heat and leaves the virus ready to infect, although more sensitive to environmental forces. But the effect of humidity is more complex: “At very high humidity conditions, as in the tropics, the virus survives longer than at intermediate levels, so the rainy seasons in the tropics are more favorable for flu transmission,” Jeffrey Shaman, an expert in seasonal flu, from Columbia University, tells OpenMind.

The similarity of SARS-CoV-2 to the flu virus and seasonal coronaviruses

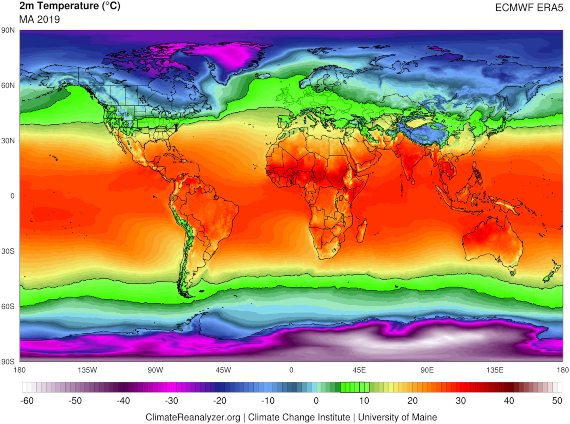

Because SARS-CoV-2 is also a lipid-coated respiratory virus, scientists suspected it might behave similarly to flu and the seasonal coronaviruses that cause the common cold. The research was divided into two areas: how the virus reacted in the laboratory to different humidity and temperature conditions, and how infections evolved in regions of the world with different climates. In April, the available results were compiled in a report by the US National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine. The conclusion was that there was “a relationship between higher temperatures and humidity levels, and reduced survival of SARS-CoV-2 in the laboratory,” but that “many other factors” could “influence and determine transmission among humans in the real world.”

In other words, the results pointed to some similarity in environmental behaviour to the flu virus. In a study in 50 cities during the early months of the pandemic, University of Maryland immunologist Mohammad Sajadi and his collaborators found that the coronavirus was spreading more easily in a narrow band of warm temperatures and low humidity than in the northern hemisphere, covering the north-central US, most of Europe and central Asia. “In the Southern Hemisphere, over the summer in the Northern Hemisphere, we did see peaks in the wintertime in Argentina, South Africa, and Brazil,” Sajadi tells OpenMind.

However, not all studies agree. From the University of Sydney, epidemiologist Michael Ward has undertaken field research in both Australia and China, observing that drier air favours the transmission of the virus, but without detecting a consistent effect of temperature. “It seems at this stage that SARS-CoV-2 transmission is more affected by humidity, whereas for flu it is both humidity and temperature,” he summarises for OpenMind.

In light of this variability in results, Shaman believes that there are no firm conclusions yet: “The results I’ve seen for COVID and weather are a bit all over the place,” he says. “Some find a temperature effect, some find a relative humidity effect, some pollution, some absolute humidity, some nothing.” The expert concedes that some studies suggest flu-like behaviour, but he stresses: “I don’t see a clear finding.” Even Sajadi, whose research points to a climatic influence, is still cautious: “I would not say that the hypothesis of seasonality is proven at this point.”

Without a consistent climate signal

“The literature on climate influence on COVID is rapidly evolving and generally confusing,” admits Benjamin Zaitchik, a hydroclimatologist at Johns Hopkins University, who is researching the influence of climate on COVID-19 in a project in collaboration with NASA. “In my own work we have yet to find a consistent and robust climate signal,” he tells OpenMind. Zaitchik attributes this confusion to the large volume of studies that have appeared, not always properly reviewed, as well as the still incomplete data and the varied methodology, but also to the fact that “epidemics in their early phases tend to be controlled by processes other than environment.”

In this regard, an epidemiological simulation published in Science last July already warned that the summer heat and humidity in the northern hemisphere would not reduce the spread of the virus, as another more powerful factor would continue to fuel its transmission: the existence of a large population still susceptible to infection. “Without effective control measures, strong outbreaks are likely in more humid climates and summer weather will not substantially limit pandemic growth,” wrote the researchers, whose conclusions have been borne out by the progression of summer infections.

The issue is further complicated by another still obscure factor, namely that not only can viruses behave seasonally, but so can our own immune system. Previous studies with rhinoviruses had already shown that cold reduces the antiviral response in the nasal cavity. Recent research has found that all infectious diseases have different seasonal patterns and that fluctuations in our immune system throughout the year can be the cause of these epidemic peaks. However, the precise mechanisms remain a mystery.

In short, seasonality is much more intricate than the simple direct impact of environmental conditions on the stability and infectivity of the virus. “The trend now is to study infectious diseases under what we call the ‘One Health Approach’,” Hadi Yassine, an infectious disease specialist at Qatar University and co-director of a recent review of the seasonality of COVID-19, tells OpenMind; “in other words, the Host-Virus-Environment interface.”

How the spread of SARS-CoV-2 will evolve in winter and in the years to come

To sum up, the experts consulted by OpenMind agree that it is reasonable for the pandemic to rebound in the northern hemisphere with the arrival of winter. “We should be prepared for the worst,” says Hassan Zaraket, an infectious disease specialist at the American University of Beirut who co-directed the recent review with Yassine. He notes: “Considering the low herd immunity worldwide, we believe the story will continue the same way, maybe until next summer when the vaccine might be available at a larger scale.” Sajadi shares the prognosis, insisting that prevention measures should not be relaxed: “My prediction is that the virus will have an easier time spreading in the fall and winter in the Northern Hemisphere. Whether the situation worsens or not will depend on how each country acts.”

But beyond the coming winter, another fundamental question is how the spread of SARS-CoV-2 will evolve in the years to come, once the pandemic has abated thanks to eventual population immunity, either through vaccines or the spread of the infection itself. It is possible, the experts venture, that our future winters will be times of flu, colds and COVID: “My instinct on this, based solely on analogy to other upper respiratory viral infections, is that if COVID-19 becomes endemic then it is likely to exhibit seasonality, and in all likelihood phase-lock to a wintertime maximum in mid-latitude climate zones,” reflects Zaitchik. But “I don’t have enough data yet,” he says. “It is a reasonable conclusion that SARS-CoV-2 transmission might show seasonality,” adds Ward.

Even assuming this prediction is accurate, there are still so many questions surrounding the new coronavirus that, unfortunately, we don’t yet know how dangerous the threat of this future seasonal COVID will be. “The big question is whether people are commonly re-infected, and if so, how often: every year, every two years, every ten years? And are repeat infections more likely to be milder, equally severe or more severe?” Shaman wonders. “Without a very effective vaccine we would have to contend with the virus.“

Comments on this publication