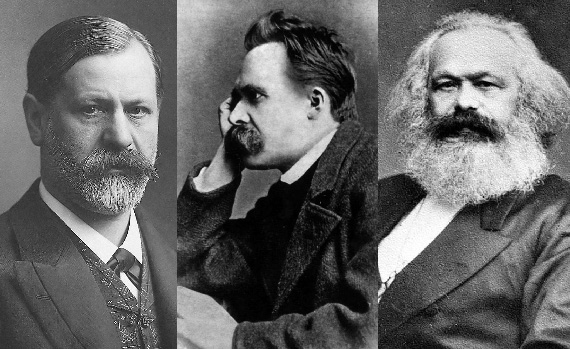

In the year 1965, in his essay “Freud and Philosophy: An Essay on Interpretation”, French philosopher Paul Ricoeur coined the expression “school of suspicion” as a form of hermeneutics that was opposed to that of affirmation. According to Ricoeur, “Three masters, seemingly mutually exclusive, dominate the school of suspicion: Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud.”

This suspicion, although stemming from different assumptions, could more or less be summarized as a distortion of consciousness about reality. Whether it comes from economic issues (Marx), weakness in a broader sense (Nietzsche) or from repression of the subconscious (Freud), a series of phenomena produced a false concept of reality, and with it, of its meaning. In addition, these three visions, in varying degrees and in different ways through distinct means and with disparate consequences, eventually produced different utopias, directly or indirectly.

It is therefore worth considering a clear question: is it fair to talk about suspicion of the vision of reality if in order to do so, it is based on other concepts, prior to those that come precisely from observation?

To answer this question and probe the nature of true suspicion, the 20th Century brought us at least three real masters of suspicion: Ludwig Wittgenstein, Kurt Gödel and Werner Heisenberg.

Each of them, in their respective fields of philosophy, mathematics and theoretical physics, aimed to analyze not only what factors affect, or could affect, the observation and representation of reality, but to see whether it is even possible to be capable of representing, even observing, reality exactly as it is. It is not surprising that in the end, the work of the philosopher Wittgenstein could seem mathematical, with implications for theoretical physics, or that the uncertainty principles could resemble philosophical work (it is no surprise that three of the books published by Heisenberg were Philosophical Problems of Nuclear Science, Philosophical Problems of Quantum Physics, or the very famous Physics and Philosophy), while any good theoretical physicist should take into account the limitations in their mathematics indicated by Gödel’s Uncertainty Principles. Finally, regardless of the tools used to try to answer them, all of their suspicions respond to the same will: ethics.

This kind of “ethicality principle” that we find in the three celebrities is top notch. Pure. It doesn’t refer to structures, which are also observed, that could deform the very observation of reality, but to the limits of observation in itself. As Wittgenstein himself writes in a letter to Ludwig von Fricker:

“My work consists of two parts: the one which is here, and of everything I have not written. And precisely this second part is the important one. For the ethical is delimited from within, as it were, by my book; and I’m convinced that strictly speaking it can ONLY be delimited in this way. All of that which many are babbling today, I have defined in my book by remaining silent about it.”

Also in Wittgenstein’s own words, “whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” Honest silence is the pinnacle of ethics. Assuming there are places we cannot reach.

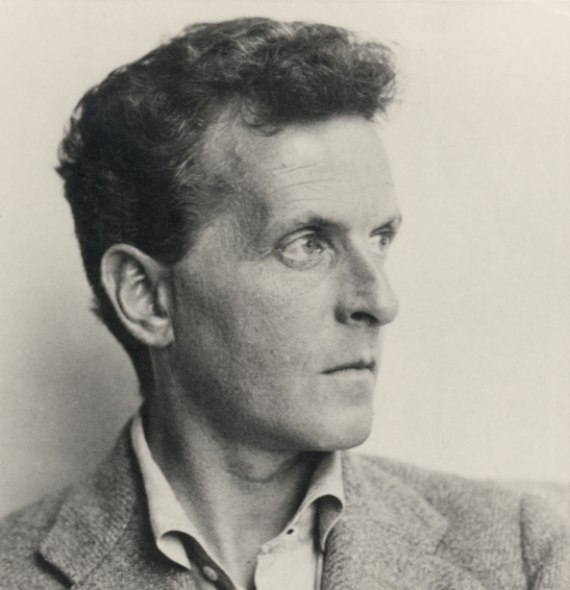

But before continuing with what he said, a pause to look at who Wittgenstein was, which is just as fascinating as what he said, and what he didn’t say.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, an exceptional story

Born in Vienna in 1901, Ludwig was the youngest of nine siblings. Many exceptional circumstances surrounded his life.

Family

His father, Karl, started an industry based on steel and iron that ended up effectively controlling these resources in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He later diversified his investments toward real estate, stock in different companies, currencies and precious materials in several countries in the world. He was not only one of the richest men at the time, but the inflation crisis that took place in the years thereafter did not seriously affect him. Ludwig gave up part of his inheritance to his siblings, making them promise that they would never give it back.

Helene, married Salzer (1879–1956), Paul (1887–1961), Hermine (1874–1950), Ludwig (1889–1951) and Margaret, married Stonborough (1882–1958). Source: Wikimedia

Art

The Wittgensteins were also great patrons of the arts. For example, one of Gustav Klimt’s best known paintings, Portrait of Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, was the portrait for the wedding of Ludwig’s sister. Naturally, their other son (the other three committed suicide), Paul, became a famous concert pianist for whom Ravel composed Piano Concerto for the Left Hand, after he lost his arm in World War I.

Ludwig also participated in the war as a volunteer, even though he could have asked for a medical discharge. He first served on a ship and later in an artillery unit in the Russian front, where he was honored for “his exceptionally brave behavior, calmness, cool head and heroism” that “earned the troops’ admiration”. During this time he began the only work he published during his lifetime, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

Roots

He studied at the Realschule Bundesrealgymnasium Fadingerstrasse in Linz, the same secondary school where Hitler studied. There is a school photo where both appear, and according to the research of author Kimberly Cornish in the book The Jew of Linz: Wittgenstein, Hitler and Their Secret Battle for the Mind, Wittgenstein was the Jewish boy Hitler referred to in Mein Kampf.

Education

He studied aeronautical engineering in Berlin and Manchester, where he registered a patent for a jet engine that later had some influence on the design of helicopter engines. He was a gardener in a monastery, primary school teacher in rural areas of Austria, a nurse, laboratory assistant and architect (he designed his sister’s whole house). He got away for years at a time in isolated houses in Norway and Ireland. Once he was in his 40s and back in Cambridge, just so he could teach, he presented Tractatus as a doctoral thesis, which had already had a remarkable influence at the time, even in places like the Vienna Circle.

Tractatus logico-philosophicus

Everything is different. Nothing is contradictory. Knowing about everything possible. And remaining silent about everything else.

For the Wittgenstein in Tractatus, reality, the world, is everything that happens. Thought is a logical representation of what happens. This logical representation of what occurs, of the world, is a proposal that has meaning. The meaning could be true, or not. The logic of the world is prior to all truth and falsehood. The meaning is expressed through language. Therefore, in the words of Wittgenstein himself, “The limits of my language are the limits of my world” and thus “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

And with Wittgenstein we can see at least two of the many limits to which we are subjected. Especially everything related to our progress:

First limitation: We are immersed in a new scientific and technological development.

We are immersed in a new scientific and technological development, which is not unprecedented. In order to compare, which implies saying that there have been no precedents, we must know how to measure issues such as the profoundness of the change they imply and the aspects that are therefore affected. And although we believe that both issues will be the greatest known to mankind, the truth is that we are right in the middle of these changes. In the process, it’s possible to hazard somewhat of a guess, but not have the complete picture.

Second limitation: All this progress, rather than making progress, as Wittgenstein warned, has a language.

All this progress, rather than making progress, as Wittgenstein warned, has a language. Artificial intelligence and its algorithms. Quantum computing and its “logic of the world is prior to all truth and falsehood” can only be described from within the limits of our language, within “the limits of our world”. The rest must be content with waiting for that to be the case. And although it almost always occurs in the same way, it’s impossible to know that that IS the case, or that we are simply lucky. There are two examples of limits we encounter when understanding what we are doing.

“It is all one to me whether or not the typical western scientist understands or appreciates my work since in any case he does not understand the spirit in which I write. Our civilization is characterized by the word ‘progress’. Progress in its form rather than progress being one of its features. Typically it constructs. It is occupied with building an ever more complicated nature. And even clarity is sought only as a means to this end, not as an end in itself. For me, on the contrary, clarity and perspicuity are valuable in themselves.” Wittgenstein in Culture and Value.

Regardless of the importance of the so-called technological revolution, the only thing for certain is that it has a limit: ourselves. Furthermore, the more profound the revolution is, the closer we will be to the limit, and the more definitive the point will be when we “find ourselves”. It becomes more and more exciting and dangerous if we do not do so with the clarity that Wittgenstein demands.

Technological progress increasingly requires deeper humanistic education. For every hour we spend on the mathematics that allow us to develop increasingly complex algorithms in environments that are difficult to understand with our language, even impossible to grasp per se like everything quantum, we should spend seven on philosophy or history. Understanding our limits is the foundation of ethics. History shows us the consequences of not understanding them, or ignoring them.

In order to make progress, and not just contribute to progress, we have to know how to be SUSPICIOUS. In capital letters. Be suspicious of what is done within your limits and be suspicious of the basis of beliefs alone. Suspicion to make progress and not to build utopias. You never know where you could end up while you search. Or do you? That’s what history is for.

Comments on this publication