The large challenge

The world’s dalliance with sustainable development has been rather platonic, beguiled by the idea and indifferent to the practice. Affirming sustainability in the abstract is an easy virtue: the call to bequeath an undiminished world to our descendants expresses a moral imperative that resonates with survival and empathic instincts deep in the human psyche. When these good intentions alight in the contentious sphere of public policy, however, the clamor of immediate self-interest often silences appeals for collective foresight and responsible action. Sustainability hangs suspended where grave crises gather in the lacuna between aspiration and deed.

When the Rio Earth Summit of 1992 adopted its optimistic Agenda 21 blueprint for a new century, the dream of a sustainable future reached an apogee. By contrast, the Rio+20 Summit of 2012 could muster only constricted vision and anodyne recommendations, bookending the world’s two-decade descent from hope and commitment to intransigence and inertia. This triumph of inaction has bred a Zeitgeist of apprehension among citizens attuned to deteriorating conditions, while more apocalyptic spirits succumb to resignation and despair, even nihilism. Trepidation and ennui are certainly understandable responses to our contemporary predicament. Nevertheless, to paraphrase Mark Twain’s comment on his own premature obituary, reports of sustainability’s death are greatly exaggerated.

Still, any exploration of a renewed basis for hope must begin with clear-eyed acknowledgement of the dire circumstances we now confront. Scientific evidence keeps mounting that current patterns of development threaten to carry the global system beyond critical thresholds into a terra incognita of destabilizing social-ecological crises (Barnosky et al. 2012). A half century ago, environmental concerns remained local, immediate, and discrete — polluted air, dirty water, and toxic soils — and the solutions were and are relatively straightforward (though often not well implemented). Since then, anthropogenic disturbances — climate change and degraded ecosystems key among them — have expanded over space and time, becoming planetary in scale, long-term in scope, and highly complex. We have pushed the biosphere into an unprecedented, perilous state; the litany of potential impacts includes rising, acidified seas; disrupted weather; spreading disease; and compromised water and agriculture systems.

We have pushed the biosphere into an unprecedented, perilous state; the litany of potential impacts includes rising, acidified seas; disrupted weather; spreading disease; and compromised water and agriculture systems.

Indeed, it seems the impacts have moved beyond potential and this turbulent future already has arrived. The rolling sequence of crises — extreme heat waves, droughts and floods, food insecurity, and financial instability, to name a few — of recent years gives immediacy and tangibility to long-term issues. As the dubious twenty-first century situation unfolds, such ominous developments likely will demand our attention with ever greater insistence, underscoring the profound imprudence of muddling on, feckless yet hoping for the best. With this awareness spreading and deepening, we can expect popular demand for a more vibrant and enduring form of development to gain urgency and traction.

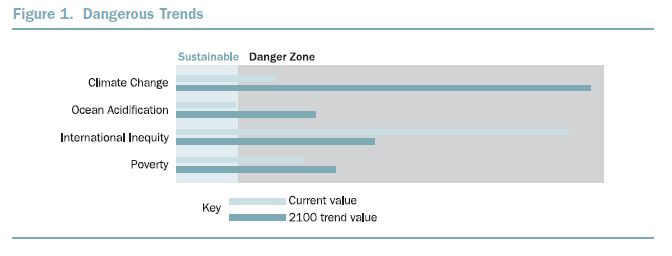

But will mobilization for change come with sufficient speed and force to counter destabilizing trends? An immense discrepancy is opening between where we are headed and where we hope to go. Figure 1 illustrates the widening gap for two environmental problems (climate change and ocean acidification) and two social problems (inequity and poverty). The trend values take us deep into an environmental danger zone, far outside Earth’s safe operating space (Rockström et al. 2009), while social disparity and destitution remain nagging problems (Raskin et al. 2010).

Hence, reaching sustainability requires a long-term political commitment to a systemic response to a host of interlocking environmental and social stresses. The broad challenges are well known: decarbonizing the energy system, improving resource-use efficiency, deploying ecological farming practices, preserving ecosystem integrity, and alleviating poverty. The means for achieving these goals also are plentiful; policy analysts have proposed a multitude of regulatory, technological and economic solutions. In the main, their reports gather dust. The world is awash in sound, unheeded proposals.

That said, a variety of efforts — public education, policy advocacy, community programs, and corporate responsibility campaigns — have yielded incremental successes, ameliorative reforms that remain a valid component of any strategy. However, gradualistic tacking against the mighty headwinds of population growth, expansionary capitalism, a spreading culture of consumerism, and a dysfunctional global governance system remains a Sisyphean endeavor.

While these deep drivers of unsustainability persist intact, systemic deterioration will continue to overwhelm piecemeal reforms. Consequently, our focus must push beyond the proximate solutions of better technology and policy to alternative values and institutions, the ultimate drivers that can underpin the transition to a resilient and decent world. Revising the ways we live and live together on this crowded planet poses the larger challenge: the search for a sustainable future becomes no less than the search for a new civilization.

The planetary phase and its potential

Sustainability, itself a capacious concept, is best understood as embedded in a still larger idea, namely, the Planetary Phase of Civilization (Raskin et al. 2002). A phenomenon of singular consequence is underway; the emergence of some form of global society. Circuits of almost everything — goods, money, people, ideas, conflict, pathogens, effluvia — spiral round the planet farther, thicker, and faster. This many-stranded ligature is binding a world of many places into one interdependent place (Anderson 2001).

The Planetary Phase is the offspring of the Modern Era. Sweeping aside the stasis and rigidity of traditionalism, modernity set in motion a revolutionary process of institutional and cultural transformation rooted in individual rights and free enterprise. Inexorably, it absorbed societies on the periphery during the long march to a world system. The industrial explosion sparked rapid expansion in production, knowledge, and population, at the price of harsh exploitation, brutal domination, and the degradation of nature. The twentieth century put the pedal to the floor, a “great acceleration” that has tripled world population since 1950 and increased the economy six-fold, with energy and material inflows and effluvial outflows soaring apace (Steffen et al. 2004).

The global reach of human affairs only continues to intensify. Footloose transnational corporations construct far-flung networks of production nodes and distribution channels. International finance generates oceanic flows of currency and capital, along with arcane, risky instruments of speculation. Humanity’s ecological footprint, once diminutive, per turbs the whole biosphere. Pressures on oil, water, and land resources increase with shor tages looming on the near horizon. Fur ther, mobile populations spread old diseases and fractured ecosystems spawn new ones, raising the specter of new pandemics. The Internet links social and research networks — and criminal rings and cyber-terrorists, as well. Political fissures open between Nor th and South, haves and have-nots, progressives and fundamentalists.

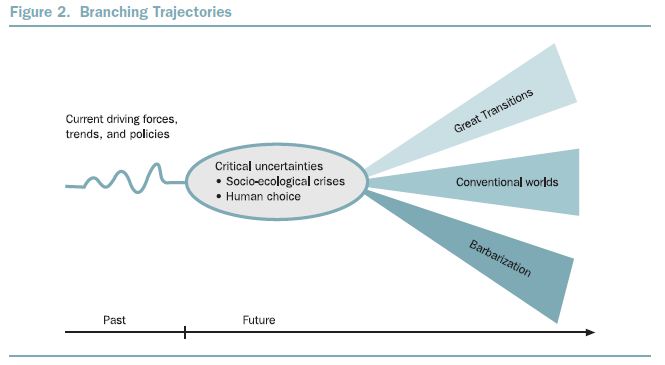

These many developments and upheavals are the birth throes of a nascent planetary formation. We can observe her fledgling shape and speculate about the kind of creature being born, but we cannot know her future. The global society that will consolidate from the turbulence of transition remains deeply uncertain and fiercely contested, beyond the ken of scientific projection and social prophesy. Looking through cloudy crystal balls, we can envision many possibilities, each a unique interplay of objective causes and subjective intentions. To a great extent, the outcome depends on how two fundamental uncertainties — socio-ecological crisis and human choice — interact and play out (Figure 2).

Although rigorous predictions are not possible, we can explore the terrain of the future by sketching plausible alternatives based on what we know from the evidence to date. These possibilities do not try to forecast what will be, but to envision what could be. Such long-range scenarios serve as prostheses for the imagination, illuminating potential perils and opportunities on the path ahead, thereby enriching our understanding of the present and guiding our steps forward. For this task, familiar depictions of the future, whether apocalyptic visions or business-as-usual projections, are too limiting. Offering a false choice between despair and complacency, these pinched images leave less familiar roads unexplored.

To organize the bewildering menagerie of plausible possibilities, consider a simple taxonomy of alternative futures (Raskin et al. 2002). Imagine three broad channels radiating from the turbulent present into the imagined future: worlds of incremental adjustment, worlds of catastrophic discontinuity, and worlds of progressive transformation (Figure 2). This archetypal triad — evolution, decline, and progression — recurs throughout the history of ideas, finding new expression in the contemporary scenario literature (Hunt et al. 2012; Raskin 2005). We refer to these divergent directions for global development as Conventional Worlds, Barbarization, and Great Transitions.

Conventional Worlds scenarios envision development as a gradual unfolding of technical innovation, market adaptation, and social learning. In these narratives, despite episodic setbacks of economic downturns, environmental crisis, and geopolitical conflict, the overall tendencies of conventional globalization persist. Economic interdependence deepens, dominant values spread, and developing regions gradually converge on rich-country patterns of production and consumption. In the neo-liberal “market forces” variant, powerful global actors advance the priority of free markets and economic expansion, emphasizing technological innovation to reconcile growth with ecological limits. In the “policy reform” variant, governments respond to nagging environmental and social problems with a comprehensive portfolio of initiatives.

The Conventional Worlds approach relies on a sequence of market adjustments and policy measures to nudge behaviors and technologies toward practices that reduce environmental pressure and social discord. It believes in — or sees no alternative to — preserving dominant institutions and cultural values. The problem is that such incrementalism leaves intact the underlying structures of socio-ecological stress: the expansionary force of market-based development, the resistance of vested interests, the intrinsic tendency toward economic inequality, and the spreading consumerist culture. Counteracting these pressures demands extraordinary vision and tenacity among world leaders, and that political will is nowhere in sight. Thus, in real historical time, over a quarter century of reform has failed to meaningfully mute, let alone reverse, unfavorable trends.

But let us assume for the moment that the Conventional Worlds pathway is plausible. Still, does this represent an appealing aspiration for civilization? To many, a world of perhaps ten billion consumers plying a globalized mall dominated by multinational corporations would seem a culturally impoverished vision. Thus, for Conventional World skeptics, these scenarios face the double-barreled critique of infeasibility and undesirability.

The second set of narratives, grouped under the rubric Barbarization, explores futures that might follow a failure of Conventional World to check destabilizing trends. In Barbarization scenarios, social polarization, geopolitical conflict, environmental degradation and economic instability reinforce one another, spiraling out of control. In the drift toward systemic crisis, civilized norms erode. One version of how this might play out — “fortress world” — envisions, in response to such upheaval, the rise of a powerful international alliance of governmental, corporate and military elements. Perhaps reluctantly, these forces of rectification impose a rough authoritarian order, creating a kind of global apartheid that finds elites in protected enclaves and an impoverished majority outside. In the “breakdown” variation of Barbarization, such effort proves insufficient to the task of stabilization so that waves of disorder spread out of control, and institutions collapse.

Great Transition alternatives, the third group of narratives, consider more elevated ambitions for the twenty-first century. They imagine ways the world might develop guided by values and institutions consonant with deep interdependence in a fragile world. In these scenarios, the Planetary Phase forges new categories of consciousness — humanity-as-a-whole, the wider web of life and the well-being of future generations. In synchrony, an ascendant suite of values — human solidarity, quality of life and identification with natural world — displaces the conventional triad of individualism, materialism and domination of nature. The broad shift expands understanding of the boundaries of citizenship, the meaning of the good life, and humanity’s place in the biosphere. Solidarity becomes the foundation for a more egalitarian social contract, the eradication of poverty, and democratic political engagement. Human fulfillment in all its dimensions becomes the measure of development, demoting consumerism and the false metric of GDP. An ecological sensibility, based on empathy, becomes the affective basis for healing Earth.

Every age creates a unique constellation of values. The idea of individual and social progress has been the sine qua non of the modern era. People lived better than their parents and expected the same for their children, a progression toward the perfectibility of “man” and society — at least for the most buoyant beneficiaries. In the early twenty-first century, with confidence in the future shaken and rising expectations suspended, faith in progress seems the atavistic worldview of a simpler, naïve time. A culture of individualism conflicts with the need for collective enterprise to create new social arrangements in an interconnected world. The anthropocentrism that sees in nature a bottomless font of resources and sink for effluvia becomes dysfunctional in an epoch showing us the earth’s limits. The association of ever-greater consumption with rising human happiness loses its thrall in lives rich in things yet poor in time to pursue meaning. Values once consistent with the modernist project now seem more apt to yield not progress, but alienated lives, the erosion of community cohesion, and a compromised ecosphere.

The global society that will consolidate from the turbulence of transition remains deeply uncertain and fiercely contested, beyond the ken of scientific projection and social prophesy. To a great extent, the outcome depends on two fundamental uncertainties — socio-ecological crisis and human choice.

The interregnum between the Modern Era and Planetary Phase is a breeding ground for crises that weaken the hold of the old consciousness. The rise of a new consciousness resonant with post-modern imperatives for extended affiliation, quality of life, and ecological resilience becomes possible, though of course not inevitable. The overarching carapace for a viable transition strategy depends on multiple efforts to articulate and propagate these incipient values. Educators, journalists, scientists, parents, and engaged citizens all have a role in spreading awareness, deepening understanding, and inspiring by example.

Paths of transition

Each Great Transition value corresponds to a domain of strategic action. The idea of human solidarity resonates with the need to generate a planet-wide political community rooted in the identity of global citizenship. Concern with human well-being directs attention to social changes and community experiments that lead to richer, more fulfilling lifestyles. The embrace of environmental sustainability, with its implied challenge to the growth-impulse of free market capitalism, brings into focus the need for a redesigned economy. In this section, then, we consider these strategic dimensions — identity, lifestyle, and institutions — in turn.

Over eons of social evolution, the spheres of community widened to embrace larger and more complex formations: families, clans, tribes, villages, cities, nations, and to some extent regions. Although particular circumstances differ, we each stand at the center of concentric circles of community (Heater 2002). Philosophers and prophets have long envisioned a ring of community that would encircle the whole human family. But cosmopolitanism remained an ideal divorced from real world history, which played out in the fragmented and antagonistic turf of tribes, fiefdoms, states, and empires.

In the Planetary Phase, the cosmopolitan abstraction has come down to earth, embedding the ethos of human solidarity in the calculus of interdependence — a condition for survival and precondition for a decent future. In many ways, the integral earth — common home of our imagined global community — seems a more natural boundary for grounding human affairs today than the arbitrary boundaries that came to delineate the imagined communities of nation-states (Anderson 1983). As national citizenship once transcended barriers within states, global citizenship may reduce divisions between them. This broader identity is basic to bridging the dangerous chasm between obsolete twentieth-century ideas and twenty-first century realities. The world-as-a-whole is becoming a single community of fate.

What, therefore, does it mean to be a global citizen? Citizenship is complex, even in its familiar guise of state citizenship. In the broadest sense, a citizen is a loyal member of a wider community that grants rights and entitlements to the individual while requiring that the individual fulfill responsibilities and obligations in return. Modern citizenship has changed and evolved in several historical waves (Marshall 1950). The eighteenth century extended economic opportunity through civil citizenship, conferring individual freedoms and acknowledging property rights. The nineteenth expanded political rights through democracy and the right to vote. The twentieth added a social dimension to citizenship through entitlement to minimum standards of welfare and economic security.

In the Planetary Phase, a fourth wave is reconfiguring citizenship, creating the basis for a new layer to its active meaning. Global citizenship carries both emotional and institutional dimensions. People become affective “citizens of the world” when their concerns, awareness, and actions embrace the whole of humanity and the ecosphere that sustains all life. Although this orientation is spreading among contemporary “citizen pilgrims” (Falk 1998), the full expression of global citizenship awaits the creation of institutions for democratic global governance.

Globalization has stimulated many supranational governance innovations including international bodies such as the World Trade Organization, negotiating processes such as the Framework Convention on Climate Change, and juridical venues such as the International Criminal Court. Rather than merely balancing the interests of competing states, together these scattered experiments could evolve to mold the foundation for a more mature form of governance beholden to the whole body politic. To date though, venues for the meaningful exercise of global citizenship are notably absent from the world stage.

One possible redress for the current anachronistic lack of representation could be developed by forming a bicameral United Nations to consist of the existing General Assembly standing for nations and a new World Parliament, elected through universal suffrage, for world citizens. A fledgling World Parliament might begin modestly as an advisory body, without the UN’s official imprimatur, postponing steps to strengthen it to full legislative authority. Yet, even as an advisory body, the parliament, as the only popularly elected global institution, would enhance accountability in the international system. By taking up transnational issues, it would offer a crucible for a global political identity to coalesce, its democratic structure anchoring a claim to authority in responses to crises.

A complementary approach not dependent on the cooperation of recalcitrant international bodies lies in the formation and spread of an explicit movement of global citizenship, a topic we return to below. The internal processes of such a movement would be a living experiment in democratic representation and decision-making, a homunculus of the supranational polity it envisions. Institutions forged in the struggle, ready-made and battle-tested, could segue into a new cosmopolitan governance system as part of a broader cultural and political rising.

The second value — quality of life — takes us from the macro-level of shaping a global demos to the micro-level of shaping a well-lived life. Most of us conduct our quotidian affairs, pursuing ambitions and managing disappointments, within the matrix of prevailing expectations and determinants. The norms and values we use to forge our identities and weigh our aspirations, and even evaluate our worth, are as natural and imperceptible as the air we breathe. Thus, we can lose sight of the historical contingency of cultural standards, which mutate and shift in the course of social evolution. The longing for material affluence and individual autonomy by the freewheeling denizens of contemporary society would be unfamiliar, perhaps offensive, to preindustrial sensibilities attuned to traditional lifestyles and group identities.

Transformative moments offer fresh occasions for perceiving and critiquing cultural assumptions. Core questions — What are we for? Who are we? How can we flourish? — are more apt to surface in times of social upheaval, when conventional ideas and cultural strictures lose their logic and sway. Such disorientation opens opportunities for new paradigms of meaning and fulfillment. At the cusp of the Planetary Phase, the ferment within subcultures seeking to downshift to lives of less stress and more time adumbrates a growing social challenge to dominant lifestyle aspirations.

The modern emphasis on material consumption as a measure of achievement and social status truncates ideas of happiness and fulfillment, elevating what psychologist Martin Seligman (2002) calls the Pleasant Life, while downplaying both personal development (the Good Life) and pursuit of some larger goal (the Meaningful Life). This hedonic pursuit is stimulated by a ubiquitous, arid advertising industry using sophisticated techniques to promote the mania for stuff and the worship of Mammon. But affluence alone hardly guarantees well-being, and, indeed, can be its undoing. Lives spent on the work-and-spend treadmill, refilling one’s purse only to empty it again on ever more goods, may be rich in things, but poor in ways that matter. Rather than fulfillment, the pursuit of over-abundance can bring stress, angst, and emptiness. With the allure of “more” always beckoning everywhere, it is easy to forget, or never even really to know, the realms of nature, relationship, and imagination that give life meaning.

In place of materialism, Great Transition strategies cultivate the idea and practice of time-rich lives of material sufficiency and qualitative abundance. In a world of shorter work weeks and at least adequate living standards for all, the well-lived life can come to embrace the quality of family, friendship, and community bonds; resonant experience of connection to nature; and varied opportunities for creativity. Fulfillment of such life choices would set the gold standard for development, something for affluent countries to turn toward and poor ones to reach for. Instead of replication of conventional practices, an enlightened development model would place human well-being at the center of its social vision, thereby leapfrogging the outmoded obstacle of the old industrial model.

Prioritizing quality-of-life values requires redesign of economic institutions, the third core strategic area. In the consumer society, the idea of “enough” is culturally seditious, undermining the sacred cow of economic growth. As the connection between the overstressed earth and overstressed lives becomes increasingly self-evident, however, the critique of material wealth as a measure of individual well-being has connected with the critique of growing GDP as a valid measure of social well-being. In any case, a shift toward less intensive consumption patterns would necessitate a parallel shift on the production side of the supply-demand equation.

Such a downshift in our conception of the economy goes against the logic of competition and profit-maximization, embedded in prevailing institutions, that impels contemporary economies to privatization and growth. Efforts to promote social and environmental responsibility in corporate and financial sectors push back, but not surprisingly, make little headway against this powerful momentum. Redesigning economies to serve non-market goals — solidarity and citizenship, flourishing individuals and communities, and ecological health — takes us beyond reform to fundamental institutional change.

Therefore, a Great Transition strategy, understanding the economy as a means for attaining the goals of society, not an end in itself, must transcend the current system that places corporate profit before the enrichment of the collective treasuries of community and nature, individual privilege before the common good, and greed before generosity. With the collapse of twentieth-century socialism and, more recently, the erosion of strong welfare states, political-economic architectures have tended toward varieties of market capitalism. The Planetary Phase opens a new chapter in the project, as old as capitalism, of envisioning a viable alternative. The guiding doctrine for a new economy would broaden the venerable principles of modernity — equality, justice, democracy, and environment — to embrace global equity, universal rights, world democracy, and the integrity of the biosphere. In so doing, said doctrine would supersede the Conventional World vision where nation-states remain politically sacrosanct, expansionary capitalism economically hegemonic, and consumerism culturally dominant.

A sustainable economy, thus, would be designed to operate within the social goals and the safe limits of the Earth system, an economy-in-society-in-nature (Costanza et al. 2012). Sustainability goals defined at global and relevant sub-global scales would serve as boundary conditions, setting constraints on the aggregate material and energy flows into economies and effluvial outflows. The goals would be set to ensure the resilience of ecosystems, the preservation of biological resources, the control of toxic chemicals into the environment, and the integrity of the climate system. In light of inevitable scientific uncertainty, two guiding principles — precaution and adaptation — are warranted in quantifying such limits on aggregate anthropogenic stress on environments. The first injects a bias of risk aversion into the process of setting constraints; the second recognizes the provisional character of goals and, therefore, the need for periodic review and modification.

Such limits would define the physical envelope within which economies must function. Since the existing system has already grown beyond this container, in some cases dramatically so and drifting further off course, the sustainability transition poses sharp challenges to existing economic institutions (Steffen 2011). An expansionary drive has always been embedded in the DNA of capitalism — Schumpeter’s “perennial gale of creative destruction” that is at once the system’s genius and Achilles’ heel, the engine of economic development and the generator of social and environmental distress. Profit-seeking entrepreneurs, prodded by competition, seek new markets, modernize production processes and devise new commodities. The financial sector plays its traditional role of lubricating the growth machine with investment funds, but with the explosion of speculative paper commodities this sector has become itself a source of growth to rival that of the “real” economy. All the while, governments work to maintain the vitality of the commercial sphere — or bail it out when that fails.

We inherit Conventional Worlds institutions forged in a world viewed as limitless. An economy for sustainability requires fundamental changes in this erroneous perspective at all levels: regulatory frameworks to align business behavior with nonmarket goals; re-chartered corporations with social purpose, not just profit, a fundamental bottom line; wide stakeholder participation so that workers and relevant community members have real say; and a financial system that suppresses speculative risk and makes consistent-with-sustainability a condition of approval for new investments. A varied mix of policy approaches would be employed across the diverse regions of a pluralistic Great Transition world, some emphasizing regulated markets, others privileging local approaches, still others tilting toward social ownership and control of capital (Raskin 2012). However implemented, deep metamorphoses in institutional structure would be precursors of the accelerated transformation needed in energy and transportation systems, metropolitan and industrial design, and agriculture and water-use practices.

Global citizenship carries both emotional and institutional dimensions. People become affective “citizens of the world” when their concerns, awareness, and actions embrace the whole of humanity and the ecosphere that sustains all life.

The unfolding of the Planetary Phase, with its discontents and unhappy prospects, will foster awareness and support for shifts on all three fronts discussed here — advancing a global political community, cultivating the art of living, and redesigning economic institutions. Together these broad arenas delineate the contours of a transformative strategy. Detailed quantitative simulation of Great Transition scenarios shows that these strategies would lead to environmental and social conditions well within the sustainability zone of Figure 1 (Raskin et al. 2010). Of course, possibility is not probability: the opportunity for transition will be squandered if forces of social change do not mobilize with sufficient speed, scale, and coherence. Even as visions of a just and flourishing civilization spur our critical imaginations and hopeful hearts, our dogged skeptical minds must ask: How do we get there from here?

Certainly, the work of policy formulation, social-ecological research, public education, and envisioning alternative futures must be pursued with renewed vigor, for all play critical roles. In addition to these efforts, though, strengthening collective action has become the essential, urgent element now needed for advancing positive transition. The recent stirrings of citizen engagement around the world give hope a point of departure; these streamlets could form a broad river of cultural and political change. For such hope to bear fruit, multiplying the numbers of citizen actions and amplifying their separate impacts becomes essential. At this critical moment, the most important innovation lies in weaving these now-disparate change agents into an overarching project, a more unified and coherent movement.

Historical agency: the missing actor

Who speaks for the Earth? Which historical agents can redirect the narrative arc of the twenty-first century? Which might be buoyed by the dynamic of change to the higher consciousness and social arrangements of a planetary age? Although each of the principal actors now on the global stage — multilateral institutions, transnational corporations, and civil society — has a role, none is a likely candidate to spearhead the transition.

The United Nations, a vast network of specialized agencies and affiliated organizations, serves as the hub of multilateralism. In the wake of World War II, the UN was created to secure world peace, while assuring human rights and spreading prosperity; the humanistic principles enshrined in its Charter, and expanded in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, remain important ethical beacons. Going beyond universal ethics, many of its founders envisioned the UN as a new supranational level of governance that would represent the interests of “we the world’s people,” its staff a true global civil service with loyalty to the greater good. Instead, during the long Cold War and beyond, it became an arena of ideological struggle, with collective interests subservient to national interests (Hazzard 1990).

The task of building an institutional architecture adequate to contemporary challenges has faltered in the hands of reluctant, irresolute nations. Yet, although enfeebled, the UN speaks with the only legitimate, collective voice of the world’s governments. In a Great Transition, the UN — reorganized, restructured, and likely renamed — would become an essential part of a governance system in which the dominance of states gives way in two directions: toward global decision-making where necessary, toward local democratic processes where feasible. For now, with the state-centric system deeply rooted and the UN showing no signs of self-invention, we must look elsewhere for a prime mover.

In the private sector, transnational corporations are the most powerful players propelling globalization toward a market-driven form of Conventional Worlds. The economy propagates through aggregation of individual corporate actions weakly constrained by regulatory frameworks. In fact, these large enterprises play a major political role in keeping it that way, investing vast resources to influence public perceptions and political decision-making. Although some organizations engage in efforts to make their operations more sustainable, their primary obligation to enrich shareholders limits the potential for the world of corporations to play a positive role in the transition. More plausibly, corporations may lead the resistance to efforts on behalf of a Great Transition.

Over recent decades, civil society has joined government and business as a third force on the international stage. This eruption of citizen energy and activism has weighed in on the full spectrum of social and environmental issues. Myriad non-profit organizations and citizen groups have altered the dynamics of international politics, engaging in intergovernmental deliberations, boycotting corporate miscreants, and mounting campaigns for human rights and sustainable development (Edwards 2011). Quieter, and perhaps most profound in their effect, their educational campaigns have spread awareness of critical issues.

Although civil society has been a vital force for sustainable development, rampant organizational and conceptual fragmentation has stifled its potential. Slicing the integral challenge into a thousand separate issues and turfs dissipates energy, fragments perspective, and undermines power. Dispersed victories here and there are overwhelmed by stronger processes of deterioration; thus, the wins cannot scale up to encompass a viable alternative path of development. At the most basic level, civil society as a whole lacks philosophical coherence, a shared understanding of the challenge and a holistic vision that can make “another world is possible” more than a slogan. Lacking an affirmative and unifying program, the civil sector remains an oppositional polyglot capable of winning important skirmishes, but losing the larger battle for a sustainable and just world.

These transnational actors — institutions, corporations, civil society — are not the only manifestations of the Planetary Phase. Earlier, we mentioned the shadow side, criminal networks, drug traffickers, arms dealers, and terrorists that also have globalized. At the same time, we find the dialectical negation of integration in the resistance of anti-globalization activists; the protectionism and xenophobia of nationally based interests; and the ideological reaction of fundamentalists to the hegemony of “modern” culture. The pull toward the ideological poles of hyper-globalization and particularism hollows out the middle ground where real solutions lie.

None of the principal actors now on the scene is likely to emerge organically from its chrysalis in the new form of a historical agent for transition. Our brief survey found government, business, and civil society interests too narrow and outlooks too myopic for the task. Indeed, these entrenched elements, with a stake in the status quo, would be as miscast for a revolutionary role as would have been feudal priests and aristocrats in leading the charge to modernity. Rather, it was the rising bourgeoisie that carried forward the earlier transformation. Now, we must look to an emergent social force forged by the Planetary Phase, one as systemic and inclusive as the challenge of shaping a planetary civilization.

We can discern the embryonic form of such a change agent in the growing chorus of concerned citizens alert to the dangerous global drift, and questioning our social arrangements, our ways of living on an increasingly fragile planet. The burning question becomes: Can this growing discontent sow a popular movement capable of channeling grievance into massive action for change? The critical actor missing from the world stage may stir in the wings, a global citizens movement (GCM) expressing the promise for a more harmonious and sustainable civilization. The crystallization of a massive GCM, though not imminent, will become more plausible as ongoing disruption erodes the legitimacy of conventional institutional structures and new visions spur collective action (van Steenburgen 1994; Dower and Williams 2002).

Like the system that spawns it, the GCM would need to become more than the sum of its parts, an integrated force rather than a mere aggregation of disjointed campaigns and projects. It would be a crucible for creating the vision and trust needed to underpin the society it seeks, an ongoing experiment, exploring ways of acting together on the path toward planetary civilization. The GCM, as a highly complex and dispersed developing formation, would need to adopt an open and exploratory process of collective learning and adjustment, a form of association in synchrony with the multiple issues and diverse traditions seeking unified expression.

The top-down structure of earlier oppositional movements will not suffice in a post-modern world suspicious of authority and leadership; nor will its converse, faith that political coherence will arise spontaneously from below. A viable movement must eschew the seductive simplifications of both vanguardism and anarchism as it navigates between the polar pitfalls of rigidity and disorder. Building and maintaining normative solidarity in a movement of such diversity poses the greatest challenge. The pull to unity can come from a deepening sense of shared destiny, aided by communications technology that spreads information and shrinks psychic distance. Pushing against unity would be lingering suspicions, barriers of language and traditions, and intransigent inequities and resentments. The challenge now is to develop the organizational and affective foundations for collective action across the differences a global movement must circumscribe (McCarthy 1997).

More than ever, we need the efforts of the past — campaigns for rights, peace, and environment; scientific research; educational and public awareness projects; local efforts to live sustainably to secure the shift to a just and sustainable mode of development. We urgently need a holistic vision and strategy: a global movement as the self-conscious agency for a Great Transition.

There are no blueprints, though this much seems clear: a vital GCM must reflect the values and principles of the transition it seeks. It would be as global as need be and as local as can be, involving masses of people across gender, race, culture, class, and nation. To thrive, it must cultivate a politics of trust: a commitment to accepting differences while nurturing solidarity. Rather than a single formal organization, it would be a polycentric political and cultural rising, a network of networks attracting new adherents through local, national, and global nodes. It would work to enlarge spaces for public participation and cultural ferment, advancing supranational identity and institutions for an interdependent age, and integrating the panoply of environmental and social campaigns as separate expressions of a common project.

If a GCM remains latent, ready to be born, then giving it life becomes the urgent frontline project for shaping a twenty-first century civilization worthy of the name. Past struggles for systemic change, such as national or labor movements, have depended on sustained holistic effort to weave together disparate grievances and component movements into an overarching formation that spoke for all. Now, the GCM awaits effective initiatives — Margaret Mead’s “small group of people” ready to change the world — for cultivating a common vision and strategy for the transition.

The nascent GCM, like all young movements, must overcome the fundamental dilemma of collective action: many sympathetic to its aims will not participate until they believe it can succeed, yet it can only succeed once people engage en masse. However, if a movement resonates powerfully with growing concerns, it can grow slowly, reach a critical mass, and then coalesce rapidly: beyond the tipping point lies a powerful force of change. A committed group of citizens, edging tenaciously forward and reaching out to multitudes of concerned people, can make all the difference.

More than ever, we need the efforts of the past — campaigns for rights, peace, and environment; scientific research; educational and public awareness projects; local efforts to live sustainably. All this is necessary, but not sufficient to secure the shift to a just and sustainable mode of development. We urgently need, as well, a holistic vision and strategy: a global movement as the self-conscious agency for a Great Transition. This would be a fitting answer to the question posed by tremulous lips everywhere: What can I do?

Facing a time of trouble, we are poised at an historical fulcrum between the world that was and the one yet to be. In stable periods, business-as-usual thinkers can, with a degree of justification, dismiss social visionaries as quixotic dreamers. In our turbulent moment, holding fast to obsolete mindsets and premises is the more utopian fantasy, while envisioning and working for a different world the more pragmatic course. If we prove too hidebound to accept the necessity of deep change or too cynical to think such change possible, we face the real danger of historical decline.

Such dystopian premonitions cannot be refuted in theory, only invalidated in practice. By taking the cultural-political leap of harnessing the potentialities of the Planetary Phase, especially by growing a systemic global movement, we can raise consciousness and community to the level of Earth. We can still pivot the trajectory of history toward a thriving civilization. This is the sustainable way.

Bibliography

Anderson, B. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. New York: Verso.

Anderson, W. 2001. All Connected Now: Life in the First Global Civilization. Boulder, CO.: West View Press.

Barnosky, A., E. Hadly, J. Bascompte et al. 2012. “Approaching a State Shift in Earth’s Biosphere.” Nature 486: 52–58.

Costanza, R., G. Alperovitz, H. Daly et al. 2012. Building a Sustainable and Desirable Economy-in-Society-in-Nature. New York: Division for Sustainable Development of the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Dower, N., and J. Williams (eds.). 2002. Global Citizenship: A Critical Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Edwards, M. (ed.). 2011. The Oxford Handbook of Civil Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Falk, R. 1998. “The United Nations and Cosmopolitan Democracy: Bad Dream, Utopian Fantasy, Political Project.” In D. Archibugi, D. Held, and M. Köhler (eds.), Re-imagining Political Community: Studies in Cosmopolitan Democracy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gallopín, G. and P. Raskin. 2002. Global Sustainability: Bending the Curve. London: Routledge Press.

Hazzard, S. 1990. Countenance of Truth: The United Nations and the Waldheim Case. New York: Penguin Group.

Heater, D. 2002. World Citizenship. Cosmopolitan Thinking and Its Opponents. London: Continuum.

Hunt, D. V. L., D. Lombardi, S. Atkinson et al. 2012. “Scenario Archetypes: Converging Rather Than Diverging Themes.” Sustainability 4: 740–772. Available at www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/4/4/740

Marshall, T. 1950. Citizenship and Social Class. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McCarthy, J. 1997. “The Globalization of Social Movement Theory.” In J. Smith, C. Chatfield and R. Pagnucco (eds.), Transnational Social Movements and Global Politics: Solidarity Beyond the State. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Raskin, P. 2005. “Global Scenarios: Background Review for the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment.” Ecosystems 8: 133–142.

Raskin, P. 2008. “World Lines: A Framework for Exploring Global Pathway,” Ecological Economics 65: 461-470.

Raskin, P. 2012. “Scenes from the Great Transition,” Solutions 3: 11-17. Available at http://www.thesolutionsjournal.com/node/1140.

Raskin, P., T. Banuri, G. Gallopín, P. Gutman et al. 2002. Great Transition: The Promise and the Lure of the Times Ahead. Boston: Tellus Institute. Available at www.tellus.org.

Raskin, P., C. Electris, and R. Rosen, 2010. “The Century Ahead: Searching for Sustainability,” Sustainability 2: 2626-2651. Available at http://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/2/8/2626.

Rockström, J., et al. 2009. “A Safe Operating Space for Humanity.” Nature 461: 472–475.

Seligman, M. 2002. Authentic Happiness: Using the New Positive Psychology to Realize Your Potential for Lasting Fulfillment. New York: Free Press.

van Steenbergen, B. 1994. “Towards a Global Ecological Citizen.” In B. van Steenbergen (ed.) The Condition of Citizenship. London: Sage Publications.

Steffen, W., A. Persson, L. Deutsch et al. 2011. “The Anthropocene: From Global Change to Planetary Stewardship.” Ambio 40: 739–761.

Steffen, W., A. Sanderson, P. Tyson et al. 2004. Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Comments on this publication