Until the frenetic scientific race currently underway succeeds in developing a vaccine for COVID-19 —or drugs to combat the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2— the best weapons we have in our arsenal to stop the pandemic are basically the same as they were in the 19th century: social distancing, the use of masks and diligent hand washing. This last measure, perhaps the only one on which all governments and health authorities in the world now agree, was the brilliant idea of a perceptive Hungarian doctor who was taken for a madman by the scientific community. If fact, he would end up dying in an asylum, without his great contribution being widely recognised during his lifetime.

This is the sad story of Ignaz Semmelweis (July 1, 1818 – August 13, 1865), born into a prosperous family of merchants in Buda, one of the two great districts that today make up the city of Budapest —the capital of Hungary, which at that time belonged to the Austrian Empire. In Vienna, the centre of that powerful empire, Semmelweis graduated in medicine in 1844 and then specialised in obstetrics. He began working in 1846 at the Vienna General Hospital, where he soon became aware of a mysterious phenomenon that took the lives of many mothers shortly after giving birth in one of the two maternity clinics associated with the hospital. In the First Clinic, approximately 10% of the mothers died from the so-called “childbed fever” (also called puerperal fever), a mortality rate that was more than double that of the Second Clinic. Even stranger, this deadly disease was less common among women who gave birth on the streets of Vienna: “To me, it appeared logical that patients who experienced street births would become ill at least as frequently as those who delivered in the clinic. What protected those who delivered outside the clinic from these destructive unknown endemic influences?” Semmelweis noted in his research.

Deeply affected, Ignaz Semmelweis began digging around for any little detail that would differentiate the two clinics, from temperature conditions to religious practices. He thought the cause might be overcrowding, but the Second Clinic was actually more popular as expectant mothers knew that the First Clinic was a more dangerous place to give birth. Semmelweis was initially unable to detect any differences. Everything was the same, except for the personnel who attended the births: in the First Clinic they were doctors and medical students, and in the Second Clinic, where far fewer mothers died, midwives and their apprentices delivered the babies. What was it that doctors did that harmed their patients? The procedures seemed to be the same.

A tragic clue

The clue that helped Semmelweis solve the mystery was the death of one of his colleagues who worked at the First Clinic, due to an infection after his finger was pricked by a student’s scalpel while performing an autopsy at the hospital. That doctor’s own autopsy revealed similarities to those women who died of childbed fever, and the light bulb suddenly went off in Semmelweis’ head. He now understood that the difference between the clinics was that the doctors and medical students dissected corpses and then went on to deliver babies with those same hands. The midwives, on the other hand, did not participate in autopsies or have contact with corpses.

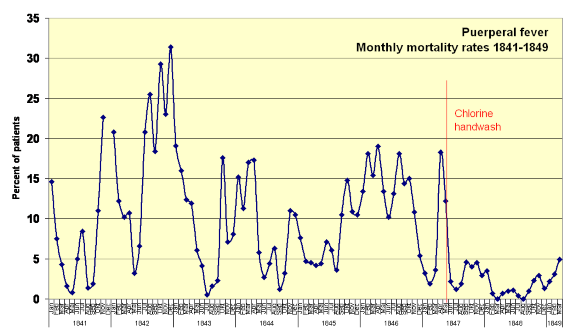

Puerperal fever monthly mortality rates for the First Clinic. Rates drop markedly when Semmelweis implemented chlorine hand washing in1847. Source: Wikimedia Commons

This brilliant insight led Semmelweis to institute in the two maternity clinics, during the summer of 1847, the practice that before examining a patient or attending a birth one had to wash one’s hands with chlorinated lime, and especially if there had been prior contact with a corpse. The measure soon proved to be very effective. In a few months, the mortality rate at the First Clinic fell drastically to equal that of the Second Clinic. That success encouraged Semmelweis, who wanted his hospital to officially implement the hand-washing measure, but that revolutionary proposal would damage his career for good.

Fighting against the scientific establishment

His biggest problem was that he could not explain his hypothesis. The “Semmelweis method” worked but was not supported by any scientific theory, in an age in which it was still not known that microbes were the cause of infectious diseases. At that time, these ailments were attributed to many independent causes, unique in each case, and that alone made it sound tremendously daring and radical for a young doctor to insist that there was only one cause: filth, and that diligent cleaning was the common remedy to prevent all cases of childbed fever.

This sounded ridiculous to the eminent scientists of Vienna, who ignored, rejected and ridiculed Semmelweis’ great idea. He, for his part, insisted that the doctors and medical students bore on their hands some invisible “cadaverous particles” that had to be eliminated with chlorinated lime (whose chemical component, calcium hypochlorite, is the “chlorine” we use today to disinfect swimming pools). Unfortunately, Semmelweis lacked a rigorous explanation for his hypothesis. What is more, many doctors felt guilty and resisted the idea that they might have been responsible for the death of their patients, or even that a gentleman’s hands could transmit disease. He fell into disgrace in Vienna and had to return to Hungary in 1849, frustrated by his dealings with the medical establishment.

The theory that exulted him after his death

Now based in Pest, he continued to apply his method of scrupulous hygiene to prevent deaths from childbed fever with great success throughout the 1850s. But his ideas were not accepted there either and he once again clashed with the medical establishment. His constant disputes with rival obstetricians, whom he even went so far as to call “irresponsible murderers”, were compounded by episodes of depression. He eventually managed to publish his research in a book: The Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever (1861), as a further attempt to demonstrate that handwashing could save many lives.

It is not clear if it was this unsuccessful battle, or premature dementia, that led to the decision by his relatives in 1865 to admit him to a hospital for the mentally ill, where he received very aggressive treatment (by some accounts he was severely beaten by the guards). He died only two weeks after his admission, at the age of 47, from sepsis that spread through his body after infection from a wound.

In that same year, Joseph Lister began applying sterilisation methods to surgery, which prevented many deaths from infections contracted during operations. Lister did so as a result of the ideas of Louis Pasteur, who identified germs as the cause of these infections. Germ theory was confirmed in the decade following Ignaz Semmelweis’ sad demise, finally explaining why he had been right. Today he is considered one of the great pioneers of antiseptic practices. The medical university in Budapest has borne his name since 1969, and the impulsive rejection of new knowledge that contradicts established norms and beliefs is today known as the “Semmelweis reflex”.

Comments on this publication