Nowadays if we speak to anyone without a strong scientific background about nuclear fusion as the energy of the future, they may respond with some vague reference to cold fusion. But “cold” is not something that applies to current fusion reactors, where the temperature reaches ten times that of the interior of the Sun. Perhaps it’s because bad news is more memorable; the cold fusion fiasco of 23 March 1989 has lived on almost like a cultural meme, overshadowing its legitimate nemesis, hot fusion.

The fusion of two light atomic nuclei such as those of hydrogen —a proton— or deuterium —a proton and a neutron— releases more energy than it consumes, which is why its potential as an energy source is studied. However, this doesn’t mean that no energy is required. On the contrary, large quantities are needed, hence the millions of degrees needed for the nuclei to be stripped of their electrons, forming a plasma that allows fusion to take place. This phenomenon occurs naturally in stars such as the Sun, where hydrogen fuses to produce helium.

In the 1920s, some scientists speculated that palladium’s ability to absorb hydrogen opened up the possibility of using this metal as a catalyst that would bring atomic nuclei close enough together to achieve fusion at room temperature. The first tentative attempts were not clear, but at the beginning of the 1980s the prestigious electrochemist from the University of Southampton (UK) Martin Fleischmann rediscovered the idea, who shared it almost like a heretical secret with his friend and colleague Stanley Pons, from the University of Utah (USA).

A secret investigation

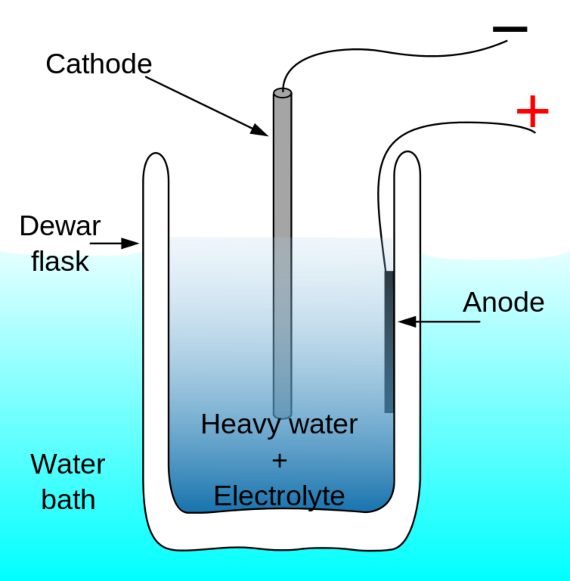

From 1983 to 1988, both scientists spent $100,000 of their own money on secret research with a simple device of their own, in which the heavy water was supposedly broken by electrolysis to obtain deuterium that later fused onto an electric pole of palladium. At a certain point in the experiments, the temperature of the reaction vessel rose to 50 °C. It was releasing heat, in other words: net energy.

To confirm their alleged discovery with new experiments, Fleischmann and Pons requested assistance from the US Department of Energy, which sent the request for assessment to Steven Jones of Brigham Young University. Jones was the appropriate expert, since he was working on another model of cold fusion catalyzed by muons, particles that are alternatives to electrons that reduce the size of the atom, facilitating fusion. Jones’ method worked, but the production of muons consumed more energy than the fusion generated.

Intrigued, Jones met with Fleischmann and Pons. Both groups agreed to send their results simultaneously to the journal Nature on 24 March 1989. However, pressured by the University of Utah, Fleischmann and Pons sent it earlier, and the day before the one agreed on, they announced the discovery to the world through a statement and a press conference.

An example of failed science

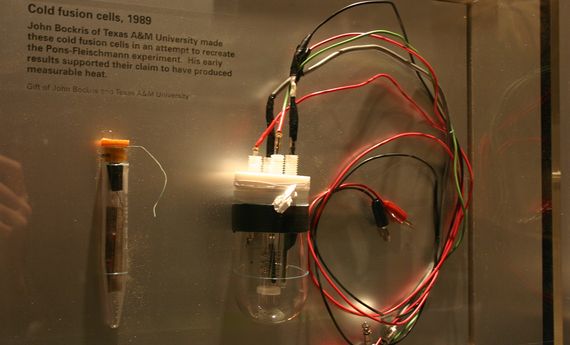

The promise of the University of Utah that the “breakthrough process” could “provide an inexhaustible source of energy” did not impress the scientific community, which reacted with great skepticism. Soon several institutions investigating hot fusion, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, reported their own results: the Fleischmann and Pons experiment did not work.

Almost immediately, cold fusion became a stigma for those who approached it, including Fleischmann and Pons, who went into exile in southern France to continue their experiments with private funding. Today cold fusion persists as one of the most cited examples of failed science.

But was it fraud? The truth is that there has never been proven any accusation of deception against Fleischmann and Pons, nor against —and this is the other side of the story— the numerous researchers who have erratically managed to replicate the observations of the two scientists. However, “erratically” is the keyword. Except for the colour of the researcher’s shirt, almost any variable, whether imaginable or not, seems to influence the possibility that cold fusion works. Perhaps the physics of nuclear fusion is still keeping to itself important revelations waiting to be discovered; but until then, it’s only science that works exactly the same on Wednesdays as on Tuesdays.

Comments on this publication