Despite what its evocative name suggests, what we know today as the Silk Road was not a route by means of which this fabric was exchanged, nor was it a single route or path that crossed the Asian continent to link the Far East with the West. Rather, it was a network of commercial, cultural and technological (and also disease) exchange routes that radiated from Central Asia. For 1,500 years these routes allowed China to be connected to the Mediterranean, playing a decisive role in the passage to the Modern Age.

Source: Wikimedia

This framework of roads had its roots in the network of routes that started in Persia and along which emissaries with messages galloped throughout the empire in the 4th century BC. However, in its final configuration, the Silk Road was officially opened in 130 BC, when the Chinese emperor sent his ambassador Zhang Quian on a diplomatic mission in search of new allies. In addition to pacts, the ambassador returned with a new breed of horses and saddles and stirrups used by western warriors. This is the first example of the Silk Road’s main function throughout history: the exchange of knowledge and technology.

The current view among historians is that the Silk Road —in service from its opening in 130 B.C. until the 14th century— was used by traders, religious, artists, fugitives and bandits, but above all by refugees and populations of emigrants or displaced persons. It is believed that it was precisely these groups of migrant populations who brought with them knowledge, tools, culture, products or crops (and with them possibly new techniques and irrigation systems). They fostered a cultural and technological “globalization” that was literally going to change the world.

Silk and sericulture

On the commercial side, the Silk Road was a small-scale, local trade network, with goods passing from one merchant to another in the markets and exchange centres that lined the route. In both directions, food and animals, spices, materials, ceramics, handicrafts, jewellery and precious stones circulated. And although its name suggests otherwise, silk was not the main commodity. What’s more, it never received this name during the almost 1,400 years that the Silk Road remained operational. The name was coined centuries later, in 1877, by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, because silk was the most valued and appreciated product among the nobles and dignitaries of the Roman Empire.

Source: Wikimedia

The exclusivity and absolute secrecy surrounding that exquisite fabric from the other end of the world seduced the highest echelons of the West. It is one of the oldest fibers known and used by humankind: the discovery of silk and the origin of sericiculture date back to China in 3rd millennium B.C. According to legend, Empress Hsiu Ling Shi —wife of the “Yellow Emperor”— accidentally discovered it while drinking tea under a mulberry tree, when a cocoon fell into the cup and began to unravel. The empress was fascinated by the shiny threads and discovered that it was the Bombyx mori worm that produced them to form its chrysalis. As a result of this discovery, she developed sericulture, and in her endeavour it is said that she also invented the bobbin and the loom.

Whether the legend is true or not, what is certain is that the first documented references to silk and its production in China date back to that time. Progressively, it spread throughout Asia, to later reach the European Mediterranean through, precisely, the Silk Road. Even so, China maintained the monopoly of the market for centuries, establishing absolute secrecy about its origin and processing. In the 6th century A.D. the Byzantine Empire took over the secret, coming to control this market in the Mediterranean basin. After the conquest of Persia by the Arabs in the 7th century, sericulture expanded definitively to Arabia, Africa and Al-Andalus.

Four inventions for a new world

Silk is an example of the products that expanded along the Silk Road, and the loom is an example of the technologies that spread and colonized the regions through which it ran, although by no means the most important. The glass and leather industries, and Western weapons and war machines travelled from the West to be introduced in the Far East. The West benefited from four inventions from China that were to shape the new world (and its new order): paper and its manufacture, printing techniques, gunpowder and the compass.

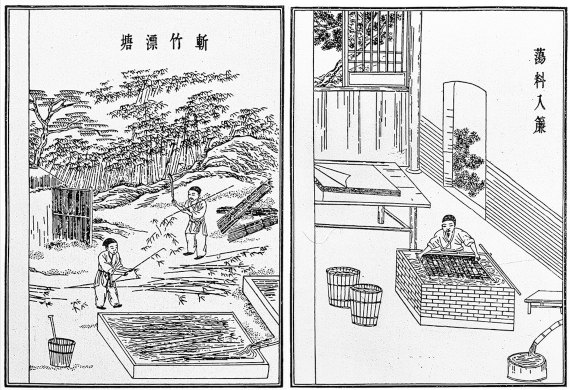

It seems that the manufacture of paper was invented in China around A.D. 104 by an officer named Cai Lun, based on the processing and subsequent pressing and drying of a mixture of vegetable fibres and water. From the 7th century, this technology would begin its expansion across the Asian continent, reaching Europe in the 12th century.

Source: Collection of reproductions of Ming dynasty woodcuts

Mechanical printing techniques emerged in China no later than the 6th century AD. The first ones were based on wooden plates on which texts were engraved and that allowed a fast mass reproduction on fabrics and on paper. In the 11th century, mobile models were developed that would later inspire Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press. The arrival of both technologies in Europe in the 12th and 13th centuries brought about a profound change, facilitating the transmission of information. This caused an enormous development in education, commerce, communications and cartography, which definitively accelerated the transition from the Dark Ages to the Renaissance and the Modern Age.

For its part, gunpowder was invented in the ninth century, probably accidentally, by Chinese alchemists or monks by “heating sulphur, realgar (arsenic sulphide) and saltpetre (potassium nitrate) together with honey, producing smoke and flames that burned everything,” as a Taoist text of that time states. It was not long before it was discovered that when this mixture was placed in a container, a violent explosion took place due to the overpressure generated by the large amount of gas released. From China, the secret of the explosive dust spread through Asia and finally, in the 13th century, it reached Europe through the Silk Road. In the West it immediately found application for military purposes, allowing the development of new armament technology, fundamental in the later conquest of the world by European powers.

The compass and the end of the Road

And finally, the magnetic compass or needle was also invented in China, probably around the 2nd century A.D., as an instrument (at first) for geomancy or forecasting. When Chinese scholars understood the behaviour and properties of the magnetite, the first compasses emerged, understood as tools for orientation. They consisted of small magnet stones or magnetized needles suspended in the air or in water.

With this form they reached Europe around the 12th century, and later, in the 14th century in the Italian region of Amalfi, they reached their current configuration, with the needle turning in a casing. With it, Italian sailors could count on an instrument that allowed them to orient themselves and to move away from the coast, propitiating the boom in maritime trade and the consequent flowering of the Italian cities states.

Credit: Victoria C

At the end of the 15th century, the limitation of magnetic declination —the angular difference between the geographic and the magnetic north poles, which depends on one’s position on the Earth’s surface— was overcome, allowing oceanic crossings.

The Ottoman Empire conquered Byzantium in 1453, aided by gunpowder and cannons, thereby cutting off communications and trade routes between East and West, which meant the end of the legendary Silk Road.

The compass played a decisive role in the great oceanic crossings that promoted the establishment of new maritime trade routes between Europe and Asia and with it the so-called “Age of Discoveries”, which marks the beginning of the Modern Age.

Miguel Barral

Comments on this publication