225 years ago, Edward Jenner administered what is considered to be the first scientific vaccine. The method perfected by the British scientist brought salvation against smallpox, a threat that would kill almost one in three of those infected. Doctors such as the Swiss-born Jean de Carro helped to take it across Europe and towards the East, while the greatest spread of the vaccine around the world was the work of the first international health expedition in history, promoted by the Crown of Spain, a bold and monumental undertaking that Jenner himself described as the noblest example of philanthropy ever attempted, under the command of the military physician Francisco Xavier Balmis y Berenguer.

As in other European countries, the vaccine was soon brought to Spain following Jenner’s experiments. Among those who immediately embraced it was the King himself, Charles IV. Like the rest of the population, he had suffered from several cases of smallpox in his family, which attracted his interest in Jenner’s vaccination as soon as he heard about it; by 1800 the vaccine was widely available in Spain. Moved by the spirit of the Enlightenment, the monarch decided to bring the vaccine to Spain’s overseas possessions, in a way trying to compensate for a historical guilt: three centuries earlier, Spanish colonisation had spread smallpox in the Americas, with such catastrophic results that the disease facilitated the decline of the Inca and Aztec civilisations. In 1803, the King signed the order to extend the vaccine to the New World, coinciding with an outbreak of the disease in Santa Fe de Bogotá.

21 orphaned Galician boys and Isabel Zendal

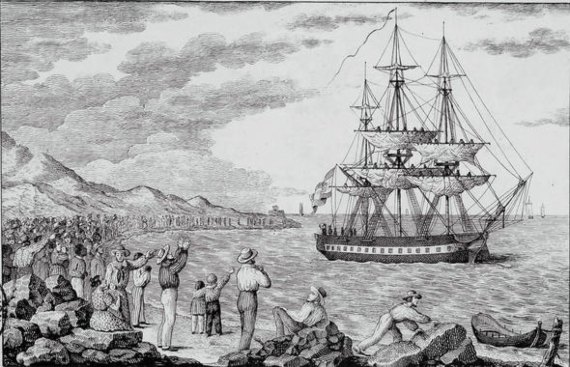

The Alicante-born Balmis (2 December 1753 – 12 February 1819), an expert in vaccinology who had already practised in the overseas territories, was selected to lead the Royal Philanthropic Vaccine Expedition. Under his command, the Catalan surgeon José Salvany y Lleopart was chosen as his deputy. The expedition was rounded out by three assistant surgeons, two interns, two nurses and, above all, 21 orphaned Galician boys aged between three and nine in the care of the rectoress of Casa de Expósitos, an orphanage in La Coruña, the nurse Isabel Zendal Gómez, the only woman on the expedition, who also brought along her own son. The expedition set sail from La Coruña aboard the corvette María Pita on 30 November 1803.

The presence of the 22 boys was necessary due to the procedure devised by Jenner. Although the Englishman was not really the first to use cowpox to immunise against human smallpox, his initial scientific contributions were his own, including the “arm-to-arm” method that allowed the cows to be dispensed with, using instead material collected from previously vaccinated people. Jenner studied the preservation of the so-called vaccine “lymph”, the fluid from the pustules that appeared after vaccination, by sealing it between glass plates or drying it on silk threads; by this second method, Jenner’s vaccine first crossed the Atlantic to Newfoundland in 1800. However, according to immunologist Catherine Mark and physician José G. Rigau-Pérez, “such conservation methods proved unreliable on journeys and in warm climates.” For an undertaking like the one conceived by Balmis, Jenner’s arm-to-arm method was a better option: children not previously exposed to cowpox or human smallpox would act as reservoirs for the vaccine.

Thus, the lymph was carried in the arms of the children in a viral relay race: two children were vaccinated before the journey; after nine or ten days, the lymph was extracted from their pustules to vaccinate two others, and so on. The children were “well treated, maintained and educated,” as the expedition’s rules stated. According to Mark and Rigau-Pérez, “the vaccination chain depended on their health, and their appearance had to impress favourably the parents of potential vaccinees.”

After a one-month stop in the Canary Islands, the María Pita crossed the Atlantic to meet with an unpromising start: in Puerto Rico, the first port of call in the Americas in February 1804, the expedition found that a vaccination campaign had already been launched there, which led to a confrontation between Balmis and the local authorities. Because of this setback, when the ship finally sailed on to present-day Venezuela the following month, only one of the children still had a single pustule from which to extract the lymph. Fortunately, it was enough to restart the chain in South America and administer 12,000 vaccines.

Two branches in the expedition

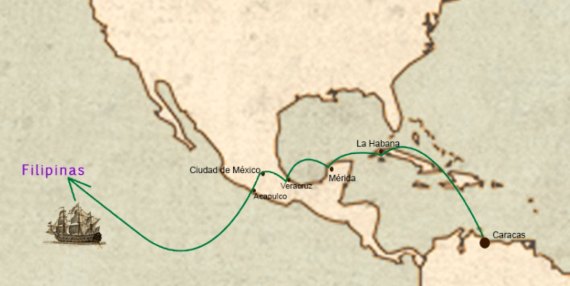

The expedition then split into two branches: Balmis continued north to Havana (Cuba), where he discovered that the vaccine had also already arrived, and then to present-day Mexico, where he vaccinated some 100,000 people before setting sail on board the ship Magellan on a new voyage across the Pacific to the Philippines, having recruited 26 Mexican children. “The parents entrusted their sons to the expedition for monetary compensation and the promise that they would be returned,” write Mark and Rigau-Perez. “Conditions on board were deplorable, with dirty, crowded quarters and miserly rations; only the generosity of other passengers and a rapid crossing allowed the expedition to avert misfortune.” For his part, Salvany embarked on a gruelling journey through jungles and mountains to present-day Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia, where he administered the vaccine to more than 200,000 people.

Given the resounding success of the expedition, which administered a further 20,000 vaccines in the Philippines, Balmis then decided to head to China, spreading the vaccination to Macao and Canton, before handing it over to the British authorities on the island of Saint Helena and finally returning to Lisbon on 14 August 1806. Salvany continued his work in the then Viceroyalty of Peru until his death from illness in Cochabamba (Bolivia) in 1810, although the campaign he had begun continued until 1812, reaching as far as Patagonia. Zendal and her son settled in Puebla, Mexico, where the other surviving “galleguitos” (little Galician orphans) also remained.

For Mark and Rigau-Pérez, the Balmis expedition was not only an extraordinary success in terms of health, but also in terms of management and administration, something that set it apart from other mass vaccination campaigns of its time; “it made use of mechanisms that would, in time, be considered essential components of an effective vaccination campaign.” And all this in the face of immense difficulties, including resistance from some local authorities, the economic interests of healers who peddled their cures, and an early version of the anti-vaccine movement: in one Peruvian village Salvany was even accused of being the Antichrist.

After the end of the Balmis expedition, nearly 170 years were to pass before the World Health Organisation declared smallpox eradicated worldwide in 1980, following a global vaccination campaign that curiously no longer used Jenner’s bovine smallpox virus, but the closely related vaccinia virus. If it is often said that science advances on the shoulders of giants, this historic achievement of mankind rested not only on those of Balmis, Salvany, Zendal and the rest of the medical team, but also on those of a total of 62 little giants, four of whom lost their lives on the journey, whose humble, unwitting contribution saved millions from the greatest plague of their day.

Comments on this publication