If today we were to read that the remains of the first Englishman in history have been unearthed along with his cricket bat, we would immediately dismiss it as fake news. But a little more than a century ago was another epoch, not only in terms of more limited scientific knowledge, but also of self-serving biases that kept such bizarre news alive for 41 years. It was not until 21 November 1953 that the greatest scientific fraud of the twentieth century, the Piltdown Man, was officially refuted.

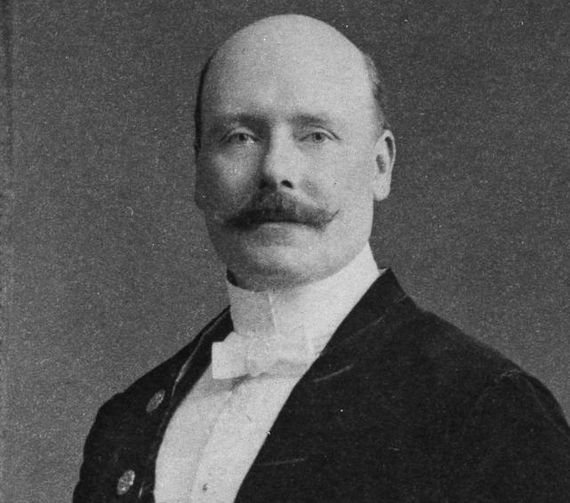

In February 1912, palaeontologist Arthur Smith Woodward, curator of geology at the Natural History Museum in London, received a letter from Charles Dawson, a lawyer by profession and an enthusiast of hunting antiquities. They were united by a long friendship centred on their common passion for fossils, and on that occasion Dawson brought great news: in a river gravel pit near Piltdown, in Sussex, he had discovered fossil fragments of a human skull. The first piece had been found four years earlier by a worker in the pit, and later Dawson himself had recovered several more pieces.

From June to September, Dawson and Woodward excavated the gravel pit, with the occasional collaboration of the French Jesuit and palaeontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. The campaign was a resounding success: in addition to additional fragments of the skull, they also recovered a partial jaw, teeth, fossils of animals and some primitive tools. On 18 December 1912, Dawson and Woodward presented to the Geological Society the brand new reconstruction of the skull of Eoanthropus dawsoni, a missing link between apes and humans that would have lived half a million years ago.

The first Englishman with a cricket bat

The discovery resonated deeply for reasons that were not exclusively scientific. As Miles Russell, archaeologist at Bournemouth University (United Kingdom) and author of Piltdown Man: The Secret Life of Charles Dawson (Tempus, 2003) and The Piltdown Man Hoax: Case Closed (The History Press, 2012) explained to OpenMind: “So many people wanted Piltdown Man to be real.” In 1907, the German Otto Schoetensack had discovered the “Heidelberg Man,” the oldest human fossil then known. In the rarefied environment that would lead to the First World War, in Britain that scoop by the Germans was uncomfortable, and the Piltdown Man was the answer. In fact, in his original letter to Woodward, Dawson had written that his specimen would rival Homo heidelbergensis.

The presumed features of the Eoanthropus, more human in its skull and more ape-like in its jaw, fitted into the erroneous theory of the time that the evolution of the human brain had preceded changes in the jaw to adapt to a new diet. Also, how could one resist the idea that the first Englishman was already carrying his cricket bat? The elephant bone carved with the shape of this sporting implement was the most bizarre side of the Eoanthropus, but not the only one that had already raised eyebrows. Some experts only objected to the reconstruction of the skull, as in the case of the anthropologist Arthur Keith, but already in 1913, the anatomist David Waterston suggested in Nature that the specimen actually corresponded to a human skull and an ape jaw.

Two years later, Dawson validated his conclusions with new findings in a second enclave near the first. However, the controversy would not disappear: in 1923, the German anthropologist Franz Weidenreich argued that the Piltdown Man was simply a jigsaw of a modern human skull and an orang-utan jaw with filed teeth.

But despite the discrepancies, the Piltdown Man managed to stay on his feet for four decades, partly because the remains were “hidden away and very few were allowed to see the real thing,” says paleoanthropologist Isabelle De Groote, of Liverpool John Moores University (United Kingdom) to OpenMind. De Groote adds that Eoanthropus “became increasingly marginalised in a time of new palaeo-anthropological discoveries.” However, she notes, a formal rebuttal required not only sufficient confidence in the methods of analysis, but also an extra dose of courage to challenge the old dogmas.

The fraud exposed

The day of reckoning finally arrived on 21 November 1953, when the London newspaper The Times echoed a study published that same day in the bulletin of the Museum of Natural History, in which scientists Kenneth Oakley, Wilfrid Le Gros Clark and Joseph Weiner applied new techniques to prove definitively that the Piltdown Man was a carefully crafted fraud that fully matched what Weidenreich had suggested three decades earlier.

Neither Dawson (who died in 1916) nor Woodward (in 1944) lived to witness the resolution of the case, and for decades the mystery about the authorship of the deception and the motives that prompted it has remained. Some suggested the involvement of Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, as a way to get his revenge against scientists who despised his spiritualism. However, for decades most of the accusing fingers pointed in the same direction: Dawson.

Extensive investigations by Russell have pointed to Dawson as the author of the fraud, a conclusion reinforced in 2016 thanks to a study led by De Groote. The analysis of the original remains with current techniques revealed that the modus operandi was the same for the creation of all the false fossils: the samples were stained brown, the cracks were filled with gravel and sealed with dentist putty, “linking all specimens from the Piltdown I and Piltdown II sites to a single forger—Charles Dawson,” the study said.

Dawson’s motivation has been attributed to his ambition to achieve scientific recognition. “Piltdown is less a ‘one off’ fraud, more the final stage in a career of hoaxes, 38 in total, that Dawson created to advance his academic standing,” says Russell. “When he died, Piltdown died with him, there being no more finds from the dig, which went on for a further 21 years after his death.” For Russell, “he was a master fraudster, a very interesting individual; almost Jekyll and Hyde like.”

Comments on this publication