The name Antoinette Louisa Brown Blackwell is often only mentioned in connection with the history of women’s rights. She was one of the pioneers of feminism at the very beginning of a journey where so much remained to be done. In her life story summed up in a single sentence, her greatest personal achievement was becoming the first ordained woman Protestant minister in the USA. But she also stood out for something that should be remembered: at a time in history when the cutting edge of science was Darwinian biological evolution, few women like her were developing and writing about the new theory. She did something else, though: she accused Darwin of sexism, arguing that his theory was flawed in this respect. And she was right.

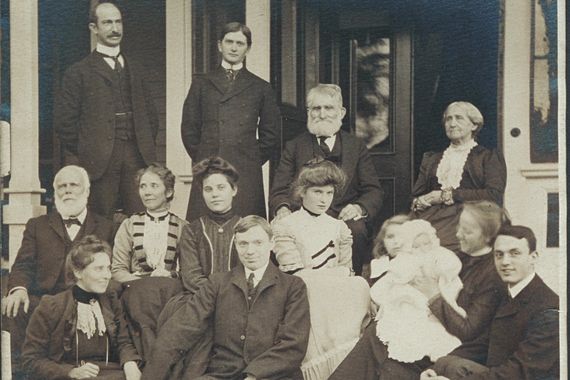

Blackwell (20 May 1825 – 5 November 1921), née Brown, was the youngest of seven children in a family from Henrietta, New York. As a child she was already noted for her intelligence, but the custom of the time did not favour the education of women, even with supportive parents. With religious faith as one of the mainstays of her life and a strong attachment to the Congregational Church, she sought a theology degree at Oberlin College in Ohio, which was off-limits to women; she was eventually allowed to attend theology courses, but was not awarded a degree recognising her studies, which denied her access to the pulpit.

From preaching to political activism

She soon began to demonstrate her drive and talent as a thinker and speaker, and through her public speaking she promoted her two most recurrent concerns: the abolition of slavery and women’s rights. Such was her charisma with audiences that her address to the first National Women’s Rights Convention in 1850 catapulted her onto a busy lecture circuit, and respect for her work eventually paved the way for her ordination in 1852.

However, her causes, tempered by her religiosity, did not always find sufficient support from the mainstream feminism of the time. She opposed divorce. She supported women’s suffrage, but emphasised more the idea that the vote was of little use if women did not achieve a greater share of power and therefore had to limit themselves to electing the men who governed them. She defended women’s access to jobs considered masculine, but always prioritised above all their duties in the home and with the family. Her sometimes controversial positions led her into heated discussions with other pioneers of feminism. These controversies, along with her marriage in 1856, drew her away from lecturing in favour of writing.

Despite her lack of scientific training, her inquiring and brilliant mind kept her attuned to the most influential thought of her time. She particularly admired the work of Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer, the driving force behind Social Darwinism. In 1869, 10 years after the publication of On the Origin of Species, she sent Darwin a copy of her first book, Studies in General Science. The founder of evolutionary theory reciprocated with a kindly letter of thanks, which he began with “Dear Sir”, unaware and little imagining that his intelligent correspondent, who signed as A. B. Blackwell, might be a woman.

Blackwell is not known to have attached much importance to this fact. But when she had occasion to read Darwin’s later work, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, published in 1871, she could not help but be indignant at the treatment of women, whom Darwin placed on an intermediate level between boy and man. He wrote: “If two lists were made of the most eminent men and women in poetry, painting, sculpture, music (inclusive both of composition and performance), history, science and philosophy… the two lists would not bear comparison.” For Darwin, competition for females in the lower species had led in the course of evolution to the development of a patience and perseverance that were the seeds of genius in man. “Thus man has ultimately become superior to women,” he wrote. For his part, Spencer argued that female labour was selfish, as it was detrimental to the reproduction of the species.

A feminine amendment to Darwinism

The view of women in Darwinism was all the more shocking because feminism at the time had embraced evolutionary theory with great enthusiasm, seeing it as a force for change towards equality based on science, as opposed to the biblical tradition of women’s subjugation to men. And so for four years Blackwell cooked up her response, which she published in 1875: The Sexes Throughout Nature, a collection of essays. For her, Darwin had made the mistake of applying an exclusively male point of view; it was women who should study women, just as she had earlier postulated that women should progress with government by women.

But Blackwell’s work was not merely an ideological dissertation; she undertook the task of meticulously collecting, organising, comparing and re-analysing Darwin’s own published data to let the conclusions come out by themselves: “As a whole, the males and females of the same species, from mollusk up to man, may continue their related evolution, as true equivalents, in all modes of force, physical and psychical.” Blackwell thus concluded that the sexes, different by nature, were made equal by the force of biological evolution.

Blackwell’s was not the only feminist critique of Darwin, but it was the first, which at the time was considered extremely daring for a woman without formal scientific training. But as she herself wrote, “only a woman can approach the subject from a feminine standpoint; and there are none but beginners among us in this class of investigations.” Not all the criticisms of her work were complimentary. But through her writings she managed to convincingly argue that, while being an otherwise sound theory—leaving aside the also blatant Darwinian racism—in its treatment of women, Darwin’s work suffered from a male bias that departed from scientific rigour.

Although Antoinette Blackwell is remembered today more as a social philosopher and feminist than as a scientist, in her later years she was admitted to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (publisher of the journal Science), to which she submitted several papers. On 2 November 1920, at the age of 95, she was able for the first time to cast her vote in a ballot box for the presidential elections; she was the only participant in the 1850 convention who lived long enough to exercise the long-awaited women’s suffrage.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication