Maria Mittelbrunn investigates how the immune system affects age-related diseases.

With each passing year, our joints are likely to ache more and more, we may find it harder to remember where we parked the car, we have less stamina when we walk, or we have put on a few extra kilos without even noticing. In other words, we feel that osteoporosis, Alzheimer’s, cardiovascular disease and diabetes, for example, are closing in on us. Are we just worrying, we ask ourselves. No, it is a very valid feeling since likelihood of these diseases increases with age. And so, we dream of being able to stop time or, if that is impossible (as it seems to be at the moment), at least to slow down or, ideally, stop these ailments of ageing. Is this possible? As it turns out, yes.

María Mittelbrunn (Madrid, 1977) spends her days in her laboratory at the Severo Ochoa Centre for Molecular Biology (CBMSO), a joint research centre funded by CSIC and the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM). This researcher explains why the health of our immune system is crucial. “These diseases have two things in common: their incidence increases as we get older and they are all associated with chronic inflammation and all involve immune system cells,” explains the biochemist. “In fact, chronic inflammation increases with age, which means that the levels of inflammatory mediators (cytokines and chemokines) in our blood increase. This process is called inflammageing. The aim of our laboratory is to investigate whether by delaying this chronic inflammation that occurs naturally with ageing we can delay age-related diseases.”

This researcher received the Young Talent Award from the Banco Sabadell Foundation for biomedical research in 2002 and the L’Oréal – UNESCO Women for Science Award in 2015. She is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Gadea Foundation for Science and the Teófilo Hernando Forum of the Spanish Royal National Academy of Medicine.

The world’s population is ageing. In Europe, the number of people aged 85 and over is expected to triple by 2050. “There is an urgent need to find therapeutic targets to prevent or delay all these diseases in order to improve the quality of life of the elderly. This is what we are working on in the lab,” says Mittelbrunn.

Chronic inflammation due to immune system impairment

But let’s start with why chronic inflammation occurs in a person. “Inflammation is a protective process that helps our body repair itself. When we get a wound, it triggers local, time-controlled inflammation to repair the tissue and close the wound. In contrast, chronic and systemic inflammation is a risk factor for all these age-related diseases,” explains the researcher.

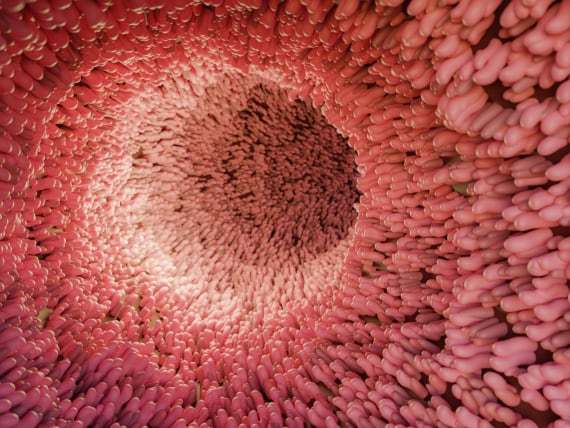

There are currently several theories that explain why chronic inflammation or inflammageing occurs, although there is no consensus. “The main causes of this chronic inflammation are the deterioration of the immune system, changes in the microbiota, the accumulation of damaged or zombie cells (senescent cells), chronic infections and intestinal permeability. Environmental pollution or poor diet can also accelerate this chronic inflammation,” she warns.

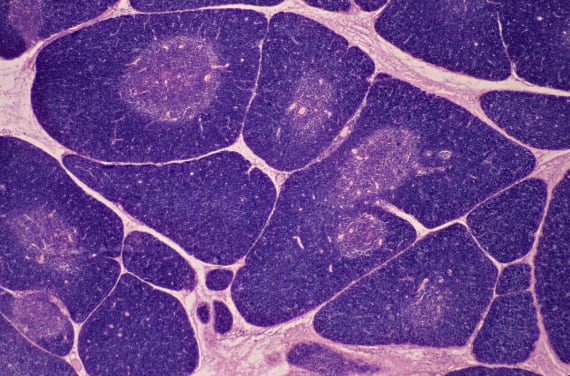

Maria Mittelbrunn’s team argues that “immune system dysfunction is the main instigator of chronic inflammation because it can trigger the other main causes.” “When an immune cell, such as a lymphocyte, gets older, it starts to make mistakes. It is no longer as perceptive, its memory fails, and it starts to have trouble distinguishing between self and non-self, between a healthy cell and an infected or tumour cell. And that’s why, as we age, our immune system begins to fail. It starts to damage tissues and we get this chronic inflammation.”

“Deterioration of the immune system is the main instigator of chronic inflammation because it can trigger the other main causes.”

As a result of this deterioration of the immune system as we age, we become more susceptible to infections, says Mittelbrunn. This was very evident during the Covid-19 pandemic, because the older we get, the more susceptible we are to the virus. But we are also more susceptible to cancer and have a higher risk of autoimmune diseases. “This has been known for many years,” explains the researcher. But recently, they have gone a step further: “We have learned that, in addition, old lymphocytes promote intestinal permeability, changes in the microbiota, the appearance of senescent cells and, with all this, facilitate the appearance of other diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, neurodegenerative diseases, loss of muscle mass, etc.”

These results place our immune system at the centre of our health, and they are essential for the prevention of infectious diseases, autoimmune diseases, cancer and also other pathologies that have not yet been studied through the prism of immunology, such as neurodegenerative or cardiovascular diseases. “Basically, these results mean that we are the age of our immune system,” concludes the scientist.

It turns out that for many years, it was thought that inflammation was the consequence of ageing, not the cause. “In fact, the levels of these inflammatory mediators (cytokines and chemokines) can be used to estimate the biological age of a person. Chronological age can be different from biological age. Chronological age is the number of years you have been alive, while biological age refers to the age of your cells and tissues as measured by physiological evidence. If a person is particularly healthy and fit for their age, their biological age may be lower than their chronological age and they may have less inflammation than their age,” she says.

But data from her team and other laboratories now suggest that this inflammation “is not the consequence but the cause of ageing, accelerating the onset of not one but several diseases at once, known as age-associated multimorbidity,” she says.

In 2020, they published an experiment in the journal Science that demonstrated the importance of th

e immune system in chronic inflammation and in age-related diseases. “We were able to desynchronise the age of the immune system from the other tissues, and what we observed is that an ageing immune system is sufficient to accelerate inflammation and the onset of cardiovascular diseases, cognitive failure, dysbiosis (alteration in the microbiota) and, in general, to accelerate ageing,” explains Mittelbrunn. Shortly afterwards, in 2021, researchers at the University of Minnesota published very similar results in Nature, which together suggest that we are the age of our immune system. Over the last decade, immunotherapy has revolutionised cancer treatment, for example. But in the next decade we will see how immunotherapy may revolutionise the treatment of age-related diseases.

Ailments that can result from chronic inflammation

But if we think about potential patients, what are the diseases we might suffer from that are most likely to develop from chronic inflammation? “Cardiovascular diseases are the most likely to arise from this inflammation, while the nervous system is much more protected from chronic inflammation than other organs, but this protection is eventually lost over the years.”

At this point, you may be wondering how we can know if we have chronic inflammation. Because ageing is not considered a disease, nor is the chronic inflammation associated with ageing, it is not diagnosed. “However,” says Mittelbrunn, “private clinics are starting to appear that calculate your biological age, measure this chronic inflammation and propose interventions to delay ageing and associated diseases. I hope that this will become more widespread and accessible to the whole of society.“

There are already treatments being used for inflammatory or autoimmune diseases (such as Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, multiple sclerosis, etc.) that could have a beneficial effect on age-related diseases. And the good news is that stopping this chronic inflammation also slows down cellular ageing, according to data from Maria Mittelbrunn’s laboratory in preclinical models.

But everyone also needs to be aware that they can do their part to prevent this inflammation. The part we cannot control is our genetic predisposition or whether we have a chronic infection. But habits are also important when it comes to prevention: “The healthy habits we are all familiar with: exercise, good eating habits, avoiding exposure to pollutants and leading a calm and stress-free life delay chronic inflammation. The fact that this ailment is not a disease in itself “does not mean that it cannot be treated, prevented or even reversed,” says the scientist.

“Prevention is the best medicine,” she continues. And public administrations can also help: “There is still a lot to be done in this area. It would be a good idea to start developing preventive policies to identify people who, because of their inflammatory state, are at greater risk than others of developing all these pathologies, and to be able to intervene before they develop.“

With all this progress and the importance of what is yet to come, it is sad to think that a few years ago María Mittelbrunn almost had to give up her scientific career due to lack of funding. “It was the funding of European projects by the European Research Council that gave me the opportunity to do science on a large scale.” Looking to the future, the researcher has great challenges ahead: “My two big dreams are, on the one hand, to contribute to a better quality of life for the elderly and to improve the scientific system in Spain. On the other hand, since there are centres in Spain that specialise in the study of cancer or cardiovascular diseases, for example, I would like to see one that focuses on ageing and inflammation.” Let’s keep our fingers crossed that there are no new budgetary obstacles and that she can make her dreams come true, for the benefit of us all.

Comments on this publication