Although 20th century books and encyclopaedias identified the German pharmacist Felix Hoffmann as the inventor of aspirin, in the last two decades disputes over the paternity of the first miracle drug have resurfaced and Wikipedia leaves it up in the air, attributing it to “scientists at Bayer.” The official version, that of the pharmaceutical company itself, continues to give sole credit to Hoffmann for the development of acetylsalicylic acid and leaves other important figures and details out of the story. The other versions are more tantalising, recounting that the controversial father of aspirin was also the man who discovered heroin, the addictive drug whose invention no one claims credit for.

In science, as in many other human disciplines, history is written by the winners. Thus, in 1934, Felix Hoffmann (21 January 1868 – 8 February 1946) told his side of the story in a footnote in a German encyclopaedia. In the 1890s, his father suffered from rheumatism and also from the side effects of the treatment at that time to relieve his pain: salicylic acid salts, which had an extremely bitter taste and, in the high doses prescribed to patients (6 to 8 grams), caused severe irritation to the stomach. The cure was a daily ordeal for Herr Hoffmann and he asked his son Felix —who in 1897 was a young researcher at the pharmaceutical company Friedrich Bayer & Co.— for an alternative.

Apart from this idealised account, the established facts are that Felix Hoffmann graduated as a pharmacist from the University of Munich with honours in 1891 and that, after an equally successful doctorate, he started work in 1894 at Bayer, a chemical company which until then had excelled in the production of synthetic dyes. Hoffmann joined the newly established pharmacology laboratory to research new drugs under the direction of Heinrich Dreser (1 October 1860 – 21 December 1924), a methodical researcher who is considered to be the first to use large-scale animal testing to prove the safety of drugs.

FROM PLANT EXTRACT TO PLAYING WITH MOLECULES

It is also a fact that as early as 1853, the French chemist Charles Frédéric Gerhardt added acetic anhydride to salicin to synthesise acetylsalicylic acid for the first time. Gerhardt was looking for a less irritating form of salicin, that yellowish, crystalline and very bitter substance that other chemists had isolated in the 1820s —from the extract of the leaves and bark of various types of willow trees, which had been used since ancient times to relieve pain and fever. Gerhardt had obtained the compound that ended up in this story, but in a very unstable and impure form. So there was little interest and all the focus was on salicylic acid, which in 1859 Herman Kolbe identified as the true active ingredient of salicin. Kolbe developed a method to synthesise it with extreme purity and on an industrial scale, which was exploited by one of his pupils, Friedrich von Heyden, who in 1874 began to manufacture and sell salicylic acid at a much cheaper price than traditional willow extracts. The problem was the severe side effects it produced, the same that embittered Herr Hoffmann.

Some sources claim that the Heyden company had started to manufacture acetylsalicylic acid as an alternative, but without a trade name, following the method developed by Schröder, Prinzhorn and Kraut in 1869. Felix Hoffmann’s great achievement in this story is that on 10 August 1897 —as he recorded in his laboratory notebook— he finally found a much better method of producing acetylsalicylic acid in a purer and more stable form.

Hoffmann was then a novice researcher who had been told by his bosses to spend the summer acetylating molecules, that is, adding the acetyl group of chemicals (CH3CO) to all kinds of pharmacologically active compounds in the hope of improving their potency or reducing their side effects. This was not a new strategy for Bayer, which had succeeded in producing its first drug, phenacetin, in 1887. So Hoffmann’s accomplishment did not attract much attention at first. In fact, Heinrich Dreser, who was responsible for all the trials prior to the launch of the drugs, had little interest in the acetylation of salicylic acid because of its bad reputation.

THE PRIOR SUCCESS OF HEROIN

What really interested Dreser was to produce codeine, and for this he asked Hoffmann to acetylate morphine. So the young researcher went on with his summer task, moved on to the next molecule and —scarcely ten days after having discovered aspirin (without knowing it yet)— achieved a very surprising result with morphine, which this time really thrilled his bosses.

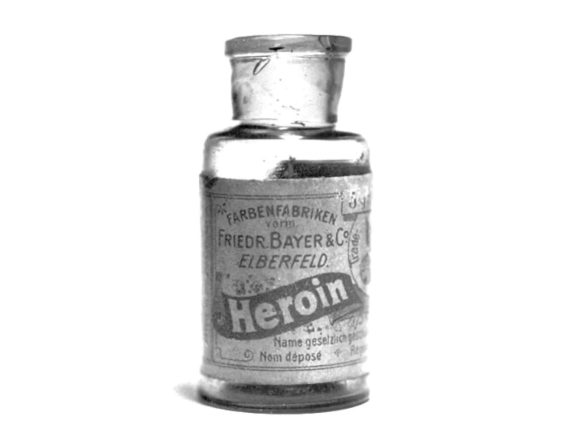

Instead of the expected codeine, on 21 August 1897, Felix Hoffmann obtained diamorphine, a substance which in tests conducted by Dreser proved to be much more effective than morphine. Delighted by this heroic achievement, Bayer’s pharmacologists named the new drug heroin, and in 1898 gave the green light to market it as “a non-addictive substitute for morphine,” intended to relieve the severe cough of tuberculosis sufferers or the severe pain of women in labour. Heroin, which was sold over the counter, was a great success for Bayer and other pharmaceutical manufacturers until it proved to be much more addictive than morphine, and was banned in 1925 by the League of Nations.

After the initial success of heroin, which Bayer omits in telling the official version of this story, Heinrich Dreser did agree to investigate the potential of acetylsalicylic acid. Animal tests demonstrated its effective properties in combating inflammation, pain and fever, and the company’s own researchers themselves proved that it did not produce the intolerable discomfort of salicylic acid. Dreser published the first scientific report on the new drug in 1899, which he immediately decided to market under the name aspirin.

CONTROVERSY OVER THE INVENTION 50 YEARS LATER

In his research paper, Heinrich Dreser did not mention Hoffmann or Arthur Eichengrün (13 August 1867 – 23 December 1949), another Bayer employee who months before his death claimed to be the true inventor of aspirin, coinciding with its 50th anniversary. Eichengrün claimed that it was he who directed the laboratory tests (which Hoffmann would have simply executed) and who pushed for the clinical trials of aspirin, overcoming Dreser’s reluctance and finally getting aspirin on the market. This alternative version of history was ignored until 1999, when scientist Walter Sneader defended it at a conference of the Royal Society to mark the centenary of aspirin, arguing that Eichengrün may have been erased from this history during the Nazi regime because he was Jewish.

Bayer Pharmaceuticals denied these claims in a press release, arguing that Eichengrün was not Hoffmann’s superior and providing his laboratory notebook and the US patent for aspirin (granted on 27 February 1900) as evidence that Felix Hoffmann must remain in history as the man who masterminded the discovery of aspirin. The truth is that neither he nor Eichengrün —nor all the researchers who contributed to this scientific endeavour before them— ever received a share of the profits reaped from the enormous commercial success of aspirin. The only one who did was Heinrich Dreser, who amassed a fortune from the royalties he collected from the aspirin and heroin trials. Disputes over who was the discoverer aside, the different versions reveal that Dreser was the man behind the most prized medicine and the most feared drug of the 20th century.

Comments on this publication