Two years after the famous sheep named Dolly arrived in the world, becoming the first mammal cloned from an adult animal cell, the Council of Europe approved the first international agreement that prohibited the cloning of human beings. It happened on January 12, 1998 and that same day nineteen countries signed the protocol

Twenty years have passed and human cloning is still not allowed in most countries of the world, although research is being done with other modalities of the technology, according to the regulations of each state. New genetic editing techniques such as CRISPR Cas/9 are forcing countries to rethink their bioethical laws and to ask the question: is it time to allow human cloning?

Red lines against human clones

When we talk about cloning we differentiate between natural and artificial. The first is present in some plants or bacteria, which produce genetically identical offspring, and also in monozygotic twin siblings (arising from the same fertilised ovule), with practically the same genetic information.

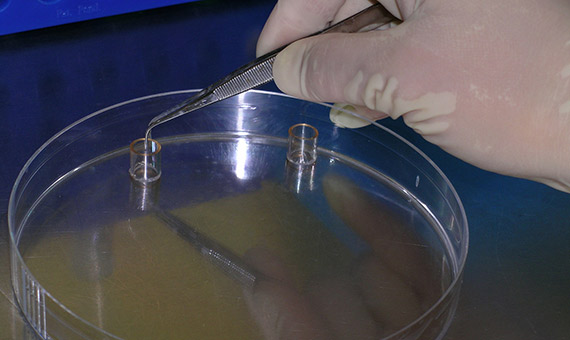

As for artificial cloning, there are three types: genetic, reproductive and therapeutic. In the genetic version, the one most used by scientists, genes or segments of DNA are copied. In reproductive cloning, whole animals are reproduced, as in the case of Dolly, while in the therapeutic technique embryonic stem cells are produced by cloning to create tissues that can replace other damaged ones.

Timothy Caulfield, director of research at the Institute of Health Law at the University of Alberta (Canada), explained to OpenMind that: “In general, the countries that have addressed the topic of cloning have banned reproductive cloning.” Within this technique, red lines have been drawn on the replication of human beings, but not of animals. In fact, following the birth of Dolly, more species have been cloned, such as calves, cats, deer, dogs, horses, oxen, rabbits and rats.

The case of the South Korean researcher Hwang Woo-suk, who in 2004 published a study in the journal Science where he claimed to have cloned human embryos for the first time, ended up in court. In addition to having failed to comply with the bioethics laws of his country, the scientist was accused of fraud for having falsifying both the procedures and the data provided. Expelled from the University of Seoul (South Korea), he was sentenced to two years in prison but finally served a suspended jail term of one-and-a-half years.

Inside and outside the borders

The common denominator in national and international standards that prohibit cloning in humans is the concept of human dignity, something that, according to Timothy Caulfield, should be analysed and defined better. In a study carried out together with Shaun Pattinson, of the University of Durham (United Kingdom), they examined the legislation on the development of human embryos, both for reproductive and non-reproductive purposes, from thirty countries (including the United States, Spain and the United Kingdom).

Although there is practical unanimity in the prohibition of embryonic cloning for reproductive purposes, in the case of cloning for other purposes not all countries prevent it. This is the situation in the United States, where some states like California allow it, or in the United Kingdom.

“There are real safety issues associated with reproductive cloning that clearly justify the regulation of the practice. But so much of the policy debate was focused on ill-defined issues of human dignity, commodification and genetic determinism,” says Caulfield, who is also a professor of Health Law and Policy.

Along with national legislation, there are other international laws such as the aforementioned protocol of the Council of Europe, which came into force in 2001 and which prohibits “any intervention seeking to create a human being genetically identical to another human being, whether living or dead”.

For its part, UNESCO approved the Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights in 1997, which also includes its opposition to human cloning for reproductive purposes, but is not mandatory.

“In 2015, the International Bioethics Committee of UNESCO produced a report which contained a recommendation calling on states and governments to produce an internationally legally binding instrument to ban human cloning for reproductive purposes,” explains Adèle Langlois, Professor of International Relations at the University of Lincoln (United Kingdom), in a conversation with OpenMind.

The biomedicine of the future

Advances in gene editing technologies and in regenerative medicine that, in some cases, use or combine cloning techniques, are ahead of bioethical laws.

In the United Kingdom, a group of researchers has been authorised to genetically edit human embryos using the CRISPR/Cas9 technique, like a US team led by Shoukhrat Mitalipov did last summer. In 2013, the scientist had already obtained human embryonic stem cells by means of therapeutic cloning, which opened the door to the development of new tissues for the patient.

“If the technology advances such that concerns over safety can be addressed, it may be that regulations banning human reproductive cloning will be revisited,” says Langlois.

According to Pattinson, in the event that the technology of nuclear transfer (passing the nucleus of a cell to an ovule without a nucleus) becomes as safe as in vitro fertilization, the laws that prohibit reproductive cloning will face a great challenge.

And what do the new generations think? In the law classes that Caulfield teaches at the University of Alberta, students debate whether or not to prohibit reproductive cloning. Although the majority had always been in favour of its prohibition, last year everyone thought that it should be allowed, “but that it should be carefully regulated,” the professor qualifies.

Laura Chaparro

Comments on this publication