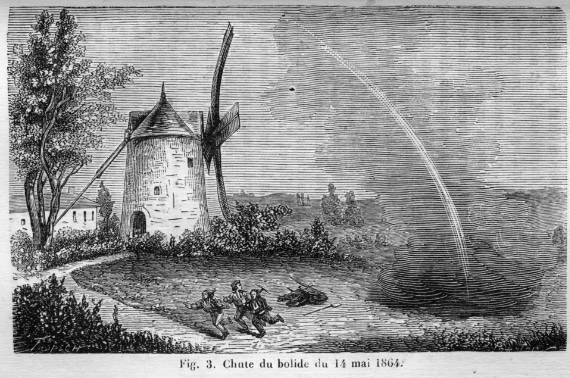

At 8pm on 14 May 1864, a fireball the size of the full moon streaked across the firmament of southern France. The object exploded in the sky with such a roar that the detonations could be heard within a radius of about 120 kilometres. Pieces of the meteorite were scattered near the village of Orgueil, in the Occitan department of Tarn-et-Garonne. The meteorite turned out to be of a rare type, but beyond its immense scientific value, it has been the subject of controversy for more than a century and a half: there are still those who argue that it is embedded with alien microfossils, and that this would support the theory of panspermia, the seeding of life on planets by objects from space.

Thousands of people witnessed the bright bolide in the sky, which was visible from southern France to northern Spain. The Orgueil meteorite arrived at just the right time in history to become the focus of in-depth scientific study: half a century earlier, the extraterrestrial origin of these rocks had been established. Another meteorite, which fell in 1806 at Alais, also in France, turned out to be of a different type from the others, the first carbonaceous chondrite meteorite to be identified. These rocky, non-metallic meteorites retain their original rock structure and are rich in organic carbon. Their appearance to the naked eye is reminiscent of a lump of coal, so in earlier times they would simply have been discarded.

Extraterrestrial origin

The spectacular appearance of the Orgueil meteorite made the news across France. The rock had exploded at an altitude of about 20 km, scattering its fragments in a corridor 20 km long and 4 km wide. A total of about 20 fragments weighing 14 kilos were recovered. The analysis was entrusted to the leading authority in the field in France at the time: Gabriel-Auguste Daubrée, Professor of Geology at the Museum of Natural History. Several studies on its chemical composition and its history were soon published.

It was already clear that this was a strange meteorite, with a composition different from other known meteorites and comparable only to the one that fell at Alais. Today, only five carbonaceous chondrites of this type, called CI, are preserved, and all the others together weigh only about seven kilos, which highlights the importance of the Orgueil find. The main characteristic of these meteorites is that they have a composition almost identical to that of the Sun, except for hydrogen and helium, so they are small fossils from the birth of the Solar System to a greater extent than other types. Orgueil probably came from a comet.

But one aspect in particular intrigued scientists. In the 19th century, the fossil nature of carbon was known, and it was inevitable that the richness of organic carbon in the Orgueil meteorite would suggest a possible origin in living organisms. Daubrée was cautious about this, but not the French astronomer and writer Camille Flammarion, an enthusiastic supporter of the existence of extraterrestrial life who is now remembered for his defence of the presence of artificial canals on Mars. Flammarion wrote that the composition of the meteorite “seems to reveal the existence of organized beings on the globes from which they came.”

It was perhaps the publicity surrounding Flammarion’s claim that attracted the attention of none other than Louis Pasteur. Immersed in the studies that would make him one of the fathers of microbiology, Pasteur decided to try to cultivate any micro-organisms that might be in the Orgueil meteorite. Curiously, there is no record of these experiments, but the story of Daubrée’s assistant, who claimed to have given the sample to the microbiologist, is accepted as true. In any case, the story goes, the results were negative; nothing living grew from the space rock.

The microfossil hypothesis

For almost a century, the Orgueil fragments lay dormant in museum drawers. Then, in 1961, the geochemist Bartholomew Nagy and his colleagues brought them back into the headlines when they published in Nature that the meteorite, whose hydrocarbons they judged to be similar to those of terrestrial life, contained “microscopic particles resembling fossil algae,” some of which showed signs of cell division. Nagy’s findings even prompted a special issue of Nature and won the approval of some scientists, but others let some air out of the balloon, claiming that the alleged microfossils were just crystals and terrestrial contaminants such as pollen grains.

A 1964 study in Science definitively burst the balloon, finding that one of the meteorite samples contained seed capsules, pollen grains and traces of charcoal, all stuck together with glue. It has never been discovered who carried out this manipulation or why, although it is thought to date from the time of the meteorite’s discovery and may have been intended to influence the debate on spontaneous generation at the time.

Nevertheless, the microfossil hypothesis lives on today through Richard B. Hoover, a retired NASA scientist. Since 2004, Hoover has published several studies defending the presence of microfossils not only in the Orgueil meteorite, but also in others. He has even recently published an atlas of microfossils from Orgueil. NASA has officially disassociated itself from these claims, which have provoked heated debate but have not found general support in the scientific community. Analysis using the latest techniques has confirmed that the meteorite, like others, contains amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, opening the door to the possibility that some of the basic building blocks of life did indeed arrive on Earth aboard extraterrestrial rocks. But the notion that complete, living, alien micro-organisms did so remains science fiction.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication