66 million years ago, an asteroid the size of a city crashed into what is now the Mexican Yucatan peninsula. The best-known consequence of that cataclysm: adios to the dinosaurs. But they were by no means the only victims; in fact, 75% of all plant and animal species on Earth disappeared. The Chicxulub impact caused the last of the five great extinctions, but many other space objects have fallen to Earth. Films such as Armageddon, Deep Impact and Don’t Look Up have played with such disasters. But are we at risk of it happening again? Can we predict it? Can we prevent it?

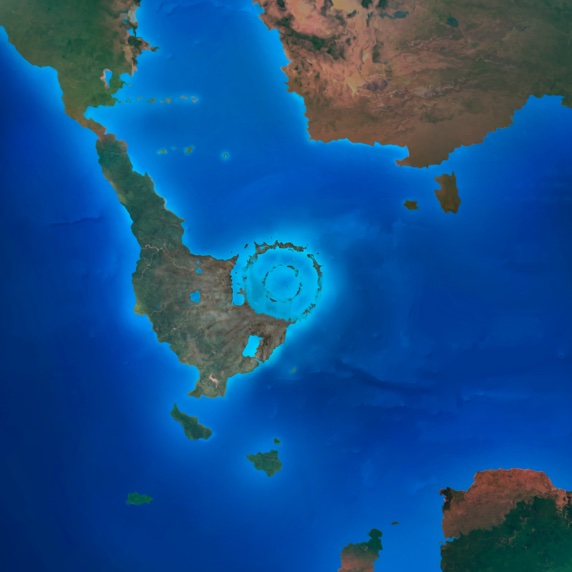

The Earth is littered with impact craters: the University of New Brunswick in Canada lists 190 confirmed ones. Some of them are visitable and spectacular. Chicxulub is not visible to the naked eye, but it left us thousands of natural wonders in the form of cenotes—natural freshwater sinkholes. The asteroid that created the Vredefort crater in South Africa around two billion years ago was perhaps twice the size of Chicxulub. Minor impact events have been recorded in human history: the largest of all, the object that exploded over the Tunguska River (Siberia) on 30 June 1908, wiping out more than 2,000 km2 of forest. On 15 February 2013, an 18-metre superbolide exploded over Chelyabinsk (Russia), briefly shining brighter than the Sun.

Preventing a major impact

Bolides—meteorites that burn up or explode in the atmosphere—are extremely common: NASA counted 556 in a 20-year period. We regularly hear about objects passing close to Earth, nearer than the Moon and even many artificial satellites. Scientists monitor near-Earth objects (NEOs), which in October 2022 exceeded 30,000. The European Space Agency (ESA) lists almost 1,500 NEOs with a “non-zero” impact probability, although it makes clear that none of those larger than 1 km will threaten us for at least a century. However, NASA scientists suggest that impacts in the past may have been more numerous than previously thought, which would mean a kilometre-long object colliding every few ten thousand years.

But if it were to happen, could we predict and prevent it? A group of physics students at the University of Leicester calculated that the ending of the film Armageddon would not have been a happy one: destroying an asteroid the size of Texas, as in the film, would have required a nuclear bomb a billion times more powerful than the largest ever built. Worse, they estimated that the Hubble Space Telescope would only have detected the film’s asteroid within eight billion miles, the minimum distance at which it could have been destroyed for its pieces to avoid Earth.

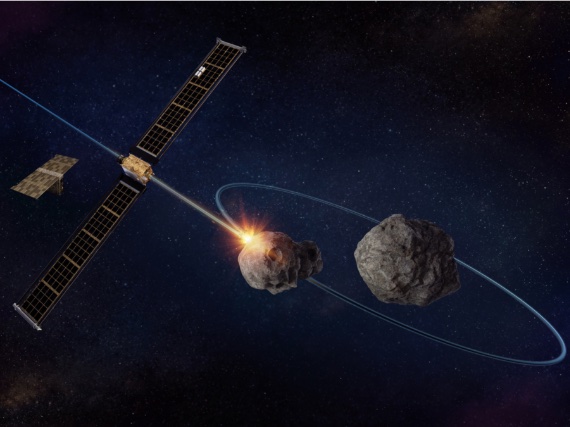

Preventing a major impact is now the focus of many research programmes. As a proof of concept, on 2 September 2022 NASA succeeded in deflecting the asteroid Dimorphos by crashing the DART (Double Asteroid Redirection Test) spacecraft into it. The problem is that this strategy would not always work: asteroids like Itokawa, discovered in 1998, are made up of a pile of agglomerated debris, like a “giant space cushion” that would not be deflected by a direct impact, according to researchers at Curtin University (Australia). In short, are we at risk? There is no clear answer.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication