As life plows its way through a sea of infection and mortality statistics, the magic of biology continues to impress in spite of the COVID-19 pandemic. Protocols to prevent the spread of COVID-19 have been adopted by hospitals around the world. These protocols are also impacting newborns who are greeted by a world in the throes of a pandemic-induced emergency. Some in the media have gone so far as to echo generational naming conventions, christening a new generation who will undoubtedly know an altered society: pandennials, coronials, quaranteens, or even baby zoomers.

Two newborns protected with face shields, an exceedingly tender image that has gone viral, illustrating the extent to which the disease has changed the parameters of “normal.”

Babies infected with COVID-19: scientific certainties and uncertainties

Data about the incidence of the illness in newborns has been confusing, although the general consensus is that little ones are not the main targets of COVID-19. Some studies suggest that there have been cases of babies who have tested positive shortly after birth, and other more reassuring studies maintain that there is no vertical transmission from mother to fetus. Irene Maté is a pediatrician and a specialist in infectious diseases. In an conversation with Openmind, Dr. Maté stresses how important it is to be careful when drawing conclusions. “Talking about what happens after childbirth requires a lot of discretion and care. There are no cases of pregnant women with COVID-19 who have spent 9 months at home. There are no immediate foregone conclusions in the world of coronavirus.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States had been suggesting the indiscriminate separation of mothers infected with COVID-19 and their newborns, until they changed criteria on April 4th, turning to a case by case approach in a country where pregnant women infected with COVID-19 represent only 2 percent of cases, according to a preliminary CDC report. Nevertheless, it is still unclear what the global levels of incidence within this group are. In order to facilitate more accurate long-term monitoring, researchers at the University of California have set up a national data registry to track the effects of COVID-19 in pregnant women and newborns.

Coming into a world of infection: prevention and protocols

Hygiene protocols for mothers with infectious diseases had already been defined before COVID-19, in the case of HIV, for example. The different protocols hospitals have adopted to contend with COVID-19 are all structured around one certainty: “existing studies have not revealed the presence of the virus in genital fluids, amniotic fluid, or in breast milk.” This comes from the Coronavirus (COVID-19) and Gestation Protocol established by the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona.

Still, this standpoint is not free from debate. According to an article in the Harvard Business Review, although current guidelines allow breastfeeding, this is not clearly conveyed in the media. On the contrary, many hospitals in the United States are systematically separating infected mothers from their newborns. The lack of consensus is obvious: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggests that medical facilities should “temporarily consider” separating mothers who have tested positive for coronavirus and newborns after “discussing the risks and benefits with the mother and the medical team”. At the time of this article, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that infected mothers can breastfeed and live with their babies provided they exercise “respiratory hygiene” and use a mask and hand sanitizer. On the other hand, on February 7th, Chinese authorities recommended that newborns not be breastfed and should be kept completely separated from their mothers, if their mothers have tested positive for the virus.

Irene Maté works in a public hospital in Madrid and advocates an individual, case-by-case evaluation to assess the risks: “With proper hygiene measures, it is feasible to avoid virus contact. In any case, the decision to breastfeed should always be respected, in this and all other contexts.” The pediatrician insists that we still do not know enough about the disease: “There are a lot of unknowns and with time we discover new data; for example loss of smell and taste as symptoms, which weren’t mentioned in the first reports coming out of China.”

According to the doctor, while current statistics indicate that COVID-19 has not been particularly prevalent among babies, it has had an indirect impact on their health. “In Madrid, at least at the beginning of the epidemic, there was a centralization of childbirth and pediatric wards were closed, although the measures taken evolved with the situation.” One of the problems resulting from these steps is that “the monitoring of newborns was complicated,” she explains.

Mom: The Guide to a World of Microorganisms

Separating mothers from babies during their first hours of life and preventing breastfeeding impedes the transfer of antibodies that mothers transmit to their babies through their milk, thus preparing them to live in a world we share with millions of microorganisms. Furthermore, “skin on skin contact helps with neonatal thermoregulation and facilitates breastfeeding,” Maté points out, and if it can be done risk-free, “it has benefits for the newborn.”

With regard to the development of the newborn immune system, Maté maintains that there are still no facts about how it will be impacted by isolation measures. “Antigens that stimulate your immune system can be found everywhere, also at home.” The doctor explains that when we are born, “our immune system is more defensive and acts against parasites or allergies, and with time it turns towards responding to bacterial or viral infections.” This shift will only not occur in an extreme case of hygiene. Even so, Maté clarifies, “isolation at home is relative, because there are always interactions with microorganisms. Continued contact between a mother’s microbiota and the newborn is fundamental.”

Child vaccination during COVID-19: a collateral risk

The vaccines that are given to newborns up to 15 months, known as primary vaccinations, have a shorter immunization period, which is why they are repeated in infant vaccination schedules. This is because a newborn’s immune system is immature and needs the repeated doses. “Other vaccines (such as MMR and chickenpox) cannot be given so early because they interact with the antibodies that the mother has passed to the baby during pregnancy and are given between 12 and 15 months”.

“All vaccines up to 15 months are essential to initiate lasting protection.”

The Spanish Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (SEIP) issued a statement at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic warning that normal vaccination programs are suffering significant delays and missed vaccinations, not only in resource poor or average countries, but also where there are sufficient resources. “The most acute point in the pandemic made it more complicated to manage the primary vaccination appointments, and families were afraid of being infected. However, failing to vaccinate a child against diseases such as measles or meningitis is very risky,” Maté elaborates.

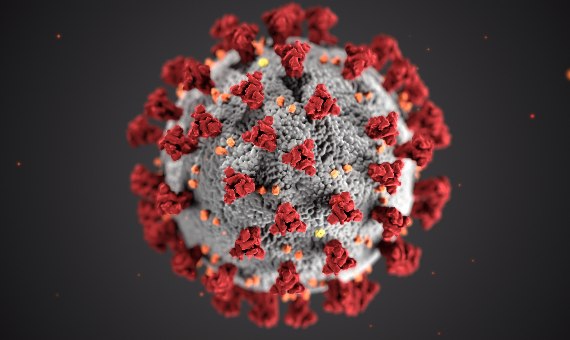

This illustration, created at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), reveals ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. Image: Unsplash

Dr. Maté reminds us that the reproduction number (R0) for measles in Spain is 17 (which implies that each case can generate another 17 cases throughout the infectious period); and in the case of meningitis, the mortality rate in Spain for children is one out of ten, quite significant compared to the current data on the COVID-19 in these patients. In March, the Spanish Association of Pediatrics’ Vaccine Advisory Committee (CAV-AEP) recommended continued regular vaccination for infants, patients with chronic illnesses, or with immunosuppression, and pregnant women; at the same time they stressed the need to improve safety conditions when administering vaccinations given the context of the pandemic.

“Este es un efecto colateral de la COVID-19 para los niños. Los umbrales de vacunación tienen que ser siempre muy altos para evitar brotes”.

An immature immune system: a strength or weakness against COVID-19?

On the other hand, it may be that a newborn’s not-yet-fully developed immune system is in part acting as an ally against COVID-19. This could explain why, to date, the disease seems not to effect the very young, as a study published in The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal concludes. As Dr. Maté reiterates, “how the disease works in general, and in respect to children, is still a mystery, but it seems that in the case of children, the immune system has a different initial response that prevents the occurrence of cytokines storms, which cause significant damage in the adult organism.” Maté also stresses that there are many open hypotheses and “other active research points to the receiver that the virus uses to communicate as a possible explanation of how it behaves in children. It could simply be that there is less quantity in the cells of young people due to biological age.”

For lay people, it is difficult to understand the logic behind vaccination as well as how to determine which groups of people should be considered priority in a situation where society has a potential vaccine against COVID-19. In this context, Irene Maté, who is a specialist in epidemiology, clarifies that “with vaccines, we seek to protect those who are more vulnerable.” We thus have to assess how a vaccine will work on this group, and if it won’t work, we have to try it on segments of the population that surround them, always aiming to protect the weakest.

If there were to be a COVID-19 vaccine, “healthcare workers should be one of the primary targets in order to prevent the spread of the disease to other patients,” but other than that it is still not clear to whom it should be administered, the doctor concludes. “For seriousness of infection, children are not a priority target group, but they are clearly carriers of the disease,” Maté explains. This dilemma is not new in the world of epidemiology. Vaccination distribution strategies are commonplace aiming to optimize the reach and the effects of herd immunity. Dr. Maté uses meningococcus as an example. “It is a type of meningitis that impacts children, but adolescents are the carriers, so they are given the vaccine, thus indirectly protecting our little ones”.

Comments on this publication