Although the traditional image that we usually associate with the scientist is that of a serious and thoughtful person, the truth is that eccentricities are not rare among the great names of science, from Albert Einstein’s aversion to socks to Nikola Tesla’s love for a pigeon. But if we are talking about extravagant scientists, few have reached the level of American biochemist Kary Mullis, winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 for his invention of the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), a technique that revolutionised biology.

The most conventional part of Mullis’ life journey (December 28, 1944 – August 7, 2019) was his childhood in rural North America. He soon began to exhibit a lively intelligence that would lead him to diverse interests, from building rockets to setting up his first business. He chose biochemistry as a career, but at the age of 24, after graduating, he published a solo paper in the journal Nature, no less, whose title, Cosmological Significance of Time Reversal, reveals the expansion of his curiosity beyond his field of specialisation. His career path would continue to be atypical: his doctorate at the University of Berkeley consolidated his profile as a biochemist, and yet at the end of it he abandoned science to devote himself to writing fiction and earning a living with jobs such as managing a bakery.

The revolutionary scientist

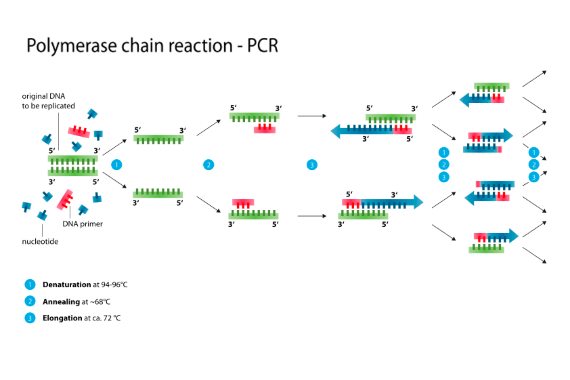

It was his return to science in the private sector that would elevate him to the zenith of his career. In 1983, while working for Cetus Corporation in California, he conceived of PCR. Four years later, he told Scientific American how the idea came to him while driving through the mountains of northern California one night in April. Making millions of copies of a DNA fragment quickly and easily was something so simple in its concept, and at the same time with such immense potential in its applications, that Mullis himself recognised that it could have been thought of by anyone. However, the technical obstacles were numerous, and the key to its success was to find the idea of using heat to separate the double chains already created and start the cycle again.

As is usual in science, other Cetus researchers contributed to the development, and subsequently several scientists contributed new refinements and variants. However, Mullis has gone down in history as the inventor of PCR, and thus he was recognised with the Nobel prize. Nowadays, any molecular biology laboratory, however small and humble, could not be considered as such without at least one thermocycler or PCR machine. Without the technique pioneered by Mullis, genomics simply would not exist.

The eccentric who saw ghosts

But we were talking about eccentricity, and thus far Mullis’ profile would not seem particularly unique. Nor was it eccentric for a Californian to surf or to marry four times. Nor was it even strange, in the context of his generation, for him to consume abundant psychotropics or even to synthesize them, taking advantage of his knowledge of chemistry; he himself acknowledged that the idea of PCR got a boost in his head thanks to another three-letter acronym, LSD. And it wasn’t the fact that he founded a company, Stargene, with the aim of selling jewellery with amplified DNA from celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, James Dean or George Washington.

The eccentricity really began to manifest itself in a more palpable way when Mullis himself recounted, in his profile for the Nobel Prize, how his recently deceased grandfather appeared at his home in California in 1986. And although many people narrate experiences of this kind, it is certainly not common for the apparition to stick around over the course of a couple of evenings, while chatting about life in California over some beers (Mullis said he drank the spectre’s beer for him). In their same vein, there are not many who would claim to have experienced an encounter in the forest with a luminous alien raccoon; Mullis denied having consumed LSD before this occurred.

The belief in astral projections, alien abductions or astrology was part of that more decidedly bizarre face of Mullis, although he did more damage to his image by denying climate change, the ozone hole or the relationship between HIV and AIDS. All this may undermine his figure as a scientific model to imitate, but not as the revolutionary genius that he was.

Javier Yanes

@yanes68

Comments on this publication