250 years ago, a child was born in Berlin who until recently many encyclopaedias remembered “only” as a great German explorer and naturalist. But Humboldt was (and meant) much more. A versatile hero of science, he created a gas mask for miners, discovered the ocean current that bears his name, explained the cause of altitude sickness, located the magnetic equator, mapped the Amazon river network and invented the isotherms and isobars that we see today on weather maps. He was also a visionary whose ideas were the seed of future theories and disciplines (such as evolution, plate tectonics and ocean dynamics) and even new awareness (such as conservationism or environmentalism).

Source: Wikimedia

In June 1799, Alexander von Humboldt (14 September 1769 – 6 May 1859) was finally able to realize his dream of an ambitious scientific expedition after investing his inheritance on the plan. During his five-year Spanish American expedition, he made most of these contributions, including his two most important contributions to science: he was the first to study human-induced climate change, and was the father of two new branches of science: biogeography and comparative climatology.

That journey shaped his thinking and opened his eyes to a new way of understanding the world and nature as one great organism within which all living beings were connected in a delicate balance. And in the Americas, Humboldt left an indelible mark, as reflected in this interactive map:

Interactive Map: The Scientific Discoverer of America

[+] Watch Fullscreen

On board the frigate Pizarro and accompanied by French botanist Aimé Bonpland, Alexander von Humboldt left the port of A Coruña for the Americas. The ship also carried 43 measuring and observation instruments —telescopes and microscopes, barometers, thermometers, a pendulum clock, compasses and even a cyanometer to measure the intensity of the blue sky— necessary for all the experiments he intended to carry out during an adventure that would last five years that would take them on a route across practically the entirety of both continents. Their first stop was Venezuela, and from there they crossed the Amazon jungle, sailing along the Orinoco and its tributaries for three months; then, after a brief stay in Cuba, they crossed the Andes, from Bogota to Peru; finally, they travelled to Mexico and the United States before returning to Europe.

The effect of man on the environment

On the way from Caracas to the Arupe River, a tributary of the Orinoco where Humboldt intended to begin his fluvial exploration, he made a stop at Lake Valencia. The naturalist measured and compared the average annual evaporation of that lake with that of rivers and lakes all over the world. He came to the conclusion that the felling of the surrounding forests and the diversion of water for irrigation were the cause of the rapid decline in the water level.

It was there that he developed his ideas on the effect of man on the environment, highlighting the climate change that this caused and warning of the risk that this could pose in the future. His claim would open the eyes of many other scientists and personalities and help lay the future foundations of conservationism and environmentalism.

After successfully completing his river journey through the Amazon jungle — demonstrating that the Orinoco and Amazon rivers were connected through their network of tributaries— and mapping the Amazon river system for the first time, Humboldt set out to explore the Andean mountains. This challenge would lead him to climb peaks and volcanoes of the imposing mountain range, and whose final point was the ascent of Chimborazo, the 6,320-metre volcano on which he set a new climbing altitude record.

Source: Wikimedia

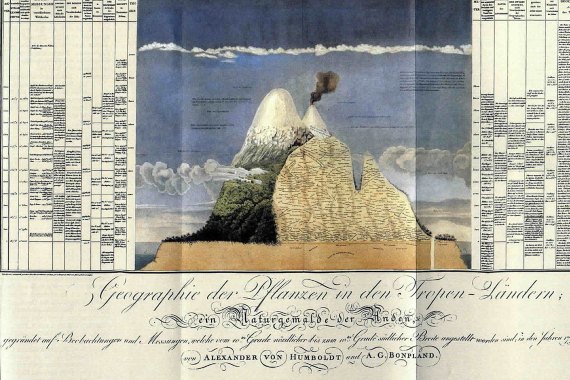

In the foothills of the Andes he began to sketch his Naturgemälde, which he would later complete in Europe: a visual representation showing a cross-section of the Chimborazo on which Humboldt drew the different plants and plant species distributed according to altitude. To the left and right of the volcano he placed several columns that offered meteorological information. Thus, when choosing a certain height of the mountain, a line could be drawn through the illustration to see the temperature, humidity or atmospheric pressure, as well as the animal species observed at that altitude. And all this information could be related to the other great mountains of the world that were located next to the Chimborazo according to their height. It was a “map” that showed the existence of climatic strips that extended across all the continents and resulted in the foundation of biogeography and comparative climatology or climatic geography.

A new way of understanding nature

In August 1804 Humboldt finally returned to Europe, to Paris, loaded down with more than 6,000 plant samples and innumerable notebooks covered with tens of thousands of annotations, observations, ideas and measurements. In the French capital he arranged, reflected upon and disseminated all the discoveries and ideas he had collected. In doing so he opened the eyes of many colleagues to a new way of understanding nature in which everything was interconnected, and the need to study it from an interdisciplinary perspective.

Source: Karin März

Considered in his time as the greatest scientific authority, after his death in Europe his figure and legacy gradually fell into oblivion from which he has only been rescued in very recent times. The same did not happen in Latin America, where Humboldt became a legendary character because of his discoveries on the continent, but even more so for his identification with the native population and the defence of their rights, for his declarations in favour of the independence of the new territories and the abolition of slavery, and for his historical friendship with another revolutionary: the politician and military man Simon Bolivar, who led the secession of Venezuela, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Panama from the Spanish Empire.

Comments on this publication