“We have had the most extraordinary year of drought and cold ever known in the history of America,” wrote former US President Thomas Jefferson to his friend Albert Gallatin in September 1816, when Jefferson was living in retirement on his farm in Virginia. In Europe, Lord Byron expressed himself in a more lyrical tone in his poem Darkness: “I had a dream, which was not all a dream. The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars did wander darkling in the eternal space, rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth swung blind and blackening in the moonless air.” At the same time, the British landscape painter William Turner was painting strange twilight skies wrapped in a translucent veil.

The chronicles recount that summer, 200 years ago, it snowed and froze in parts of Europe and North America. Crops were ruined, triggering the worst famine of the nineteenth century. A medallion of the time from Germany read: “Great is the distress, O Lord, have pity.” That year, 1816, became known as “the year without a summer,” a climatic anomaly that affected the northern hemisphere, whose cause at the time was obscured and whose consequences were unexpected. For example, the shortage of oats to feed the horses inspired the German inventor Karl Drais to create his Laufmaschine or velocipede, the first bicycle.

The apocalyptic poem by Byron was just one of the literary works born from that unusually cold summer. Gathered in a villa next to Lake Geneva (Switzerland), the romantic author and his guests entertained themselves during their forced seclusion by writing horror stories. Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin, then still the girlfriend of poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, began to shape her immortal work Frankenstein; or the Modern Prometheus. Byron’s personal physician, John William Polidori, conceived his work The Vampyre.

But the effects of this glacial wave were global and lasting, as recounted by Gillen D’Arcy Wood, Professor of English at the University of Illinois (USA), in his book Tambora: The Eruption That Changed the World (Princeton University Press, 2014). Wood explained to OpenMind that typhus was especially intensified in countries such as Ireland and Italy, and that large-scale mortality in Europe led to mass migration to Russia and America. “In the longer term, European governments began to develop policies of trade protection, social welfare and humanitarian aid,” he says.

The consequences were not confined to Europe; in Southeast Asia economic disaster led to the revival of slavery. Torrential rains in India brought about a cholera epidemic that swept the world, killing tens of millions. Famine in Yunnan, in southwestern China, forced farmers to switch from rice cultivation to the more profitable opium. “By mid-century, Yunnan was the largest opium-growing region in the world. It was the beginning of what we know as the Golden Triangle,” says Wood.

In North America, the year without a summer helped to shape the current United States: “The huge demand for grain from the northwest frontier leads to land speculation, Indian removal, and rapid settlement of states such as Indiana, Illinois, and Kentucky,” explains Wood. When that economic boom declined and prices returned to normal, along came the so-called Panic of 1819, the first depression in the history of the country, whose effects continued until 1820 and included the halt of the expansion westward.

The cause of all this disaster did not begin to be unravelled until a century later. In the early twentieth century, scientists began to study the impact of volcanic eruptions on climate. By analysing historical records, the American atmospheric physicist William Jackson Humphreys linked the phenomena from the year without a summer to the violent eruption of the Tambora volcano on the Indonesian island of Sumbawa, which began in April 1815. The speculative hypothesis of Humphreys was confirmed in 1979 by the oceanographer Henry Stommel and his wife Elizabeth in their article “The year without a Summer,” published in Scientific American.

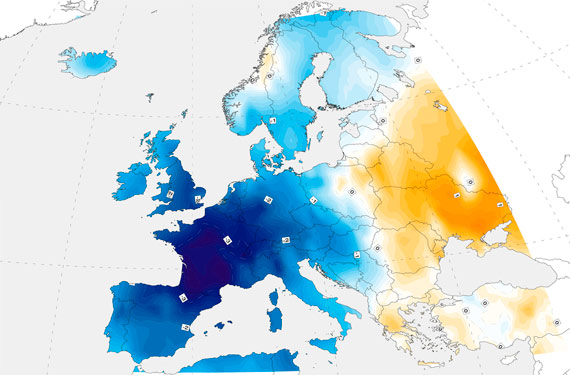

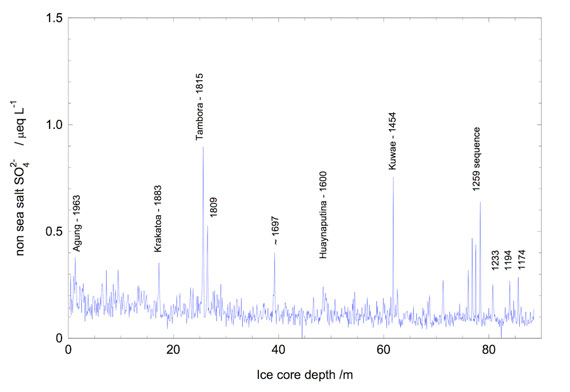

Evidence of the long range of the emissions from Tambora has been found in the high sulphur content in samples of polar ice from the time, says paleoclimatologist Robert Mulvaney of the British Antarctic Survey to OpenMind from a research vessel in the Weddell Sea (Antarctica). “Very large eruptions (such as Tambora) can lift material very high in the atmosphere, and into the stratosphere,” explains Mulvaney. “Once in the stratosphere, the sulfur dioxide can oxidise into sulphuric acid, which is taken up by tiny water droplets to form a haze in the stratosphere that can reflect incident sunlight back away from the Earth, causing less light to penetrate through the atmosphere, and the Earth to cool.” This sulphuric acid circulating in the stratosphere is then detected in ice cores. In this way, scientists can estimate the volume of emissions from an eruption.

But even though nowadays the idea has spread that Tambora was the cause of the year without a summer, this is really only half true. The truth is that cooling had already begun before the eruption, between 1809 and 1810. In the late eighteenth century, a period of low solar activity called the Dalton Minimum began, which lasted until 1830 and reduced temperatures worldwide. And the story does not end there; in the ice cores, scientists found the smoking gun of another strong eruption, which occurred in 1808 or 1809 and which must have contributed to cooling even before Tambora. Of this eruption we knew absolutely nothing.

We learned more in 2014, when a team of geologists, volcanologists and historians from the University of Bristol (UK) managed to unearth two historical accounts written by, respectively, the Colombian scientist Francisco Jose de Caldas and Peruvian Jose Hipolito Unanue. Both men describe atmospheric anomalies typically associated with volcanic eruptions, which have allowed the researchers to suggest a date: December 4, 1808, give or take a week.

Where the eruption happened is still a mystery. As noted by the first author of the work, the Spaniard Alvaro Guevara-Murua, “the eruption must have occurred in the tropics,” but “the location may be remote.” As an example, in 1883 the atmospheric signs of the eruption of Krakatoa took six days to reach Colombia. Somewhere in the world, perhaps on a remote island, perhaps under the sea, a volcano partially responsible for the year without a summer is still waiting to be discovered.

Comments on this publication