For the longest time they were considered a poor man’s version of plants; immobile but ubiquitous, like plants, they form part of the landscape, albeit in a much more subtle and hidden way than their showier relatives. Their unobtrusive behaviour goes hand in hand with the fact that they are the Russian roulette of nature’s supermarket: some are delicious, but others can send us to our graves. All this has made fungi the almost exclusive territory of a select caste of experts—the mycologists—in whom we admire that gift of being able to distinguish the edible from the lethal, even when to the layman’s eye they appear identical.

Genetic analysis has revealed that fungi form a separate kingdom in nature, closer evolutionarily to animals than to plants, but which billions of years ago chose to follow its own path, specialising in decomposing everything that dies—and sometimes also the living. Fungi are therefore nature’s greatest recycling system, which raises some interesting possibilities for us. Here we look at some of the most surprising fungi we know of, some of which can be our allies in the search for sustainability solutions.

Zombie-creating fungi

Although Ophiocordyceps unilateralis was discovered for science by the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace in 1859, the fungus known as the zombie-ant fungus has become so popular through reports and documentaries that it has even starred in horror fiction, in a novel made into a movie.

Cicadas have their own zombie fungu that once infects them, rots part of the insect’s abdomen, replacing it with a white mass of spores. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

But leaving aside the gore, the truth is that this fungus is a true prodigy of evolution, an example of how a species can develop mechanisms to take advantage of others at its convenience. In this case, the fungus spores attach themselves to Camponotus leonardi ants, a common resident of tree canopies. By colonising their bodies, they alter their behaviour, forcing them to descend to the ground, the ideal niche for the fungus. There, the infected ants cling with their mandibles to the sinew of a leaf and then die. Finally, the fungus fructifies and releases new spores.

But Ophiocordyceps is not unique in this respect. Cicadas have their own zombie fungus, Massospora cicadina. Once infected, it rots the back part of the insect’s abdomen, replacing it with a white mass of spores. At the same time, the fungus injects its victims with a type of amphetamine called cathinone, which sends the insects into a frenzy with only one goal: sex. The unfortunate zombies are unaware that they have also lost their genitals, but their unsuccessful attempts at mating are used by the fungus to infect new victims.

Champions of extravagance

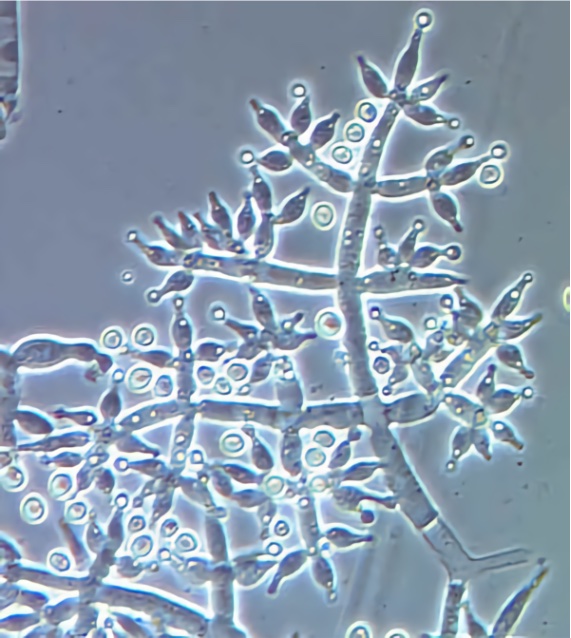

Although we are used to thinking of fungi as mushrooms, in reality most fungi do not form these structures, properly called fruiting bodies or sporocarps, which serve to disperse the spores. Generally, fungi grow discreetly, hidden from view, spreading their hyphae—their body, in the form of filaments—which usually form a mycelium, an interconnected network.

Fungi form mushrooms in an incredible variety of shapes and colours, such as Clathrus archeri, known as devil’s fingers. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

But beyond white button mushrooms, truffles or boletus—the kings of popularity for their culinary use—fungi form mushrooms in an incredible variety of shapes and colours. Some of them seem to be designed on a whim, ranging from the beautiful to the terrifying. Among the latter, any list of striking mushrooms will always include Hydnellum peckii, aptly named the bleeding tooth fungus, or Clathrus archeri, known as octopus stinkhorn or devil’s fingers and reeking of rotting flesh. At the opposite extreme, Phallus indusiatus or veiled lady captivates the eye with its delicate lace skirt, and Hericium erinaceus or lion’s mane looks like a false beard. There are also some 80 species of mushroom that glow in the dark because they contain a bioluminescent molecule called luciferin.

The largest living thing on the planet…

In 1998, scientists in the USA discovered that the Armillaria ostoyae—or honey mushroom—growing in a forest in the Blue Mountains of Oregon is actually a single clonal organism that sprawls in a network covering more than 950 hectares. With an estimated weight of up to 35,000 tonnes, it has gone down in the record books as the largest living thing on the planet. The estimated age of what is colloquially called the humongous fungus ranges from 2,400 years to more than 8,000 years.

The Armillaria ostoyae can sprawl in a network covering more than 950 hectares and live more than 8,000 years. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Armillaria ostoyae is a parasitic fungus; it attacks conifers and is difficult to eradicate, not least because of its habit of spreading. The one in Oregon is not the only specimen that has grown to immense proportions: in the state of Michigan, USA there is another individual of a related species, A. gallica, which occupies 37 hectares and has been estimated to be 2,500 years old.

…And the fastest

The organism capable of the fastest movement among living things is not an insect, and certainly not the cheetah, which holds the crown for speed among mammals; curiously enough, it is a fungus, even though in some cultures a sedate person is derogatorily called a mushroom (or a couch potato in English). The speed record goes to the humble Pilobolus crystallinus, whose preferred habitat is the faeces of herbivores, which ingest its spores deposited on grass.

To disperse, Pilobolus crystallinus has devised a system of pressurised turgid vesicles that expel its spores up to 2.5 metres away. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

To disperse, this fungus has devised a system of pressurised turgid vesicles that expel its spores up to 2.5 metres away. But even if the journey is not long, their velocity is incredible: in 2008, a study with high-speed cameras estimated their acceleration at between 20,000 and 180,000 g; in 2 millionths of a second they accelerate from 0 to 20 km/h, then reach a maximum speed of 300 km/h. This feat has earned the fungus the nickname the “Dung Cannon”.

Nuclear yeast

Since the first nuclear power plants began operating in the 1950s, the world has accumulated around a quarter of a million tonnes of spent nuclear fuel, with another half of this amount having been reprocessed. Over the years, this radioactive waste has contaminated soils and aquifers, and a foolproof and definitive solution to its permanent storage has yet been found.

There are fungus, such as the yeast called Rhodotorula taiwanensis, that can grow in radioactive environments and can also absorb heavy metals. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

What to do with this waste? Looking to nature for help, US scientists discovered that a yeast called Rhodotorula taiwanensis can grow in highly radioactive environments and can also absorb heavy metals. Unlike the bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans, which for years has been the champion of radiation resistance, this fungus is quite at home in acidic environments and is able to form biofilms, making it a promising option for the bioremediation of soils contaminated by radioactive material and for keeping potential leaks from nuclear graveyards at bay. Radiation-resistant fungi have also been found at Chernobyl.

Plastic eaters…

In the field of bioremediation, scientists are looking for a solution to the urgent problem of plastic pollution that not only fouls our land and water, forming large patches in the ocean, but also lingers in the long term in the form of microplastics that have invaded every last corner of the planet, including our food and our very bodies.

Many types of bacteria and fungi eat plastics, such as Pestalotiopsis microspora, that can digest and break down polyurethane. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In 2011, researchers at Yale University discovered strains of the fungus Pestalotiopsis microspora in the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador that can digest and break down polyurethane, a plastic we know mostly in the form of foams, but which is present in our lives in countless applications. P. microspora thrives on this plastic even in the absence of air and light, making it an ideal candidate for bioremediation in landfills. This is not the only case; many types of bacteria and fungi eat plastics, and in recent years the list of our potential fungal allies in the fight against plastic pollution has increased dramatically.

…And oil

With oil being a fossil remnant of the living things that populated the Earth millions of years ago, and fungi being nature’s great decomposers, it would seem odd that these organisms haven’t found a way to tap into such a succulent source of carbon. And indeed, they have. In 2015, researchers at Haverford College collected samples of oil-soaked sand from the Gulf of Mexico following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and found several species of marine fungi that degrade both hydrocarbon chains and polycyclic aromatics, oil pollutants with toxic effects on humans and nature.

Certain plants capable of growing in oil-contaminated soil are able to do so thanks to a fungus called Trichoderma harzianum that lives in their roots. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

They are not the first oil-eating fungi known. In fact, the oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus), cultivated as food in many areas of the world, also produces enzymes that digest hydrocarbons, as well as absorbing heavy metals such as mercury. In Canada, scientists discovered that certain plants capable of growing in oil-contaminated soil were able to do so thanks to a symbiotic fungus called Trichoderma harzianum that lives in their roots.

The most fearsome fungi

Although poisonous mushrooms might spring to mind in the list of the scariest fungi, they really shouldn’t pose the slightest risk as long as we leave the picking to those who really know how to spot them. The real threat from fungi, however, is much more invisible and unpredictable, and comes from those that we may encounter without knowing it or being able to avoid them, and which can make us ill.

Sporotrichosis, called rose-gardener’s disease, is caused by the fungus Sporothrix schenckii, which is present in plant matter. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

We don’t tend to think of fungal infections as a big danger; the most common ones, such as candidiasis or athlete’s foot, are easily treated, and even aspergillosis is rare in healthy people. But it can be worse; for example, Pythium insidiosum is a fungus present in stagnant water and soil that infects mammals, including humans, causing severe ulcerative skin lesions. Sporotrichosis, called rose-gardener’s disease, is caused by the fungus Sporothrix schenckii, which is present in plant matter, and can affect the skin and spread through the body. The greatest risk is for immunocompromised people, for whom any fungal infection can be lethal.

However, this dark side of fungi is dwarfed by their many benefits. From them we obtained penicillin and other antibiotics, the drugs that have saved the most lives in history. Leaving aside the famous recreational uses of so-called “magic mushrooms”, nowadays mushrooms are an immense source of new compounds that scientists are researching with possible therapeutic applications against a number of diseases.

Javier Yanes

Comments on this publication