Half a century ago, on May 18, 1967, the governor of Tennessee signed the abolition of a law that had remained in force for 42 years. The repeal process happened with astonishing rapidity: on May 15, a lawsuit was filed against the law, and the next day the State Senate voted for its annulment after less than three minutes of debate. The end of the so-called Butler Act, the law against the teaching of evolution in Tennessee schools, was as curious as had been its beginning, not to mention the famous Scopes Monkey Trial that it led to.

In 1925, farmer and member of the Tennessee House of Representatives John Butler, a parishioner of the Primitive Baptist Church, drafted a bill “prohibiting the teaching of the Evolution Theory in all the Universities, Normals and all other public schools in Tennessee, which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, and to provide penalties for the violations thereof.” The text stated that it would be illegal “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals,” setting fines of between $100 and $500 for offenders.

Butler’s idea was not unexpected; as early as 1922 he promised in his election campaign that he would work to protect schoolchildren from the evolutionary ideas published by Charles Darwin more than half a century earlier. Butler’s text was widely adopted by both houses of the Tennessee Assembly. On March 21, 1925, the law was ratified with the signature of Governor Austin Peay. Butler boasted that 99 people out of 100 in his district thought like him, and that he did not know anyone “in the whole district that thinks evolution—of man, that is—can be the way scientists tell it.” However, for many it was a surprise that the law was approved by Governor Peay, a devout Christian, but with a progressive tendency.

The irruption of science into rural America

The explanation is that the Butler Act was more than a conflict between creationism and evolutionism, says Adam Shapiro, a science historian at Birkbeck University in London and author of Trying Biology: The Scopes Trial, Textbooks, and the Antievolution Movement in American Schools (University of Chicago Press, 2013). According to what Shapiro tells OpenMind, in the 1920s, Darwinian evolution was not something new; however, the expansion of compulsory schooling into rural America and the irruption of science into the social order, traditionally dominated by religion, was a big change.

The Butler Act was “partly a protest, partly a political compromise,” summarizes Shapiro; Governor Peay supported the teaching of religion, but was confident that the law would go unnoticed. At the same time, he hoped it would help him stimulate the construction of new schools and the training of teachers without arousing the suspicions of conservative rural communities.

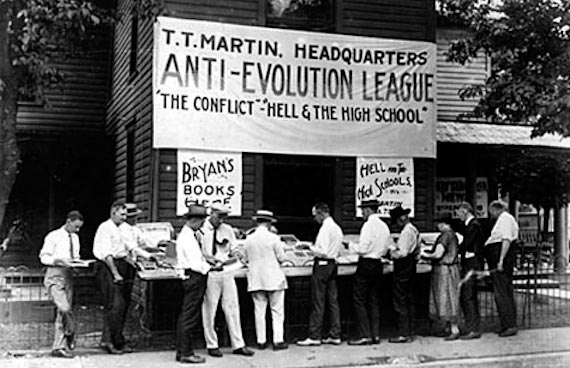

What Peay did not imagine was what would happen next. As news of the new Tennessee law spread, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) offered to defend anyone accused of violating the Butler Act. The announcement of the ACLU came to the attention of George Rappleyea, an engineer and manager of the Cumberland Coal and Iron Company in the small town of Dayton, Tennessee. Inspired by his rejection of religious fundamentalism and the desire to show the world its consequences, he persuaded local leaders that a court case would put Dayton on the map and revitalize its economy. To act as a defendant, Rappleyea persuaded a 24-year substitute biology teacher named John Scopes, who was not even sure of having taught evolution in his classes.

The trial against Scopes was held in Dayton in July 1925, with an enormous display of press and radio that made it known all over the world. The prosecution and defense lawyers, the Democratic presidential candidate, former Secretary of State and fervent Christian William Jennings Bryan, and the agnostic and member of the ACLU Clarence Darrow, respectively, were intensely dramatic. The story of the trial would inspire the play Inherit the Wind, which debuted in 1955 and would reach the cinema in 1960.

The “dead law” that was still in force

The jury issued a guilty verdict for Scopes, who was sentenced to pay a $100 fine. However, the sanction was overturned on a technicality. After the Scopes Trial, no other teacher was ever arrested for violating the Butler Act. According to Shapiro, the ACLU fought for its repeal in 1955, on the occasion of the premiere of Inherit the Wind; however, “they were told by the governor’s office that it was effectively a dead law, but that there was no desire to ignite a political fight by trying to repeal it.”

Thus the law remained in force, but in hibernation, until 1967 when the teacher Gary Scott was dismissed for violating the act. Scott’s reaction led to his reinstatement to avoid negative publicity, but the teacher filed a lawsuit against the law and the Tennessee legislature took advantage of the occasion to vote for its repeal.

The Butler Act case has not been the only one. According to Shapiro, “even in states without anti-evolution laws, not teaching evolution was often simply the standard practice. For most schools, avoiding controversy was more important.” The historian adds that today the struggle continues, although the teaching of Genesis as a historical account has had to be reinvented successively in the so-called “creation science” and Intelligent Design to overcome legal changes.

Meanwhile, the municipality of Dayton continues to cling to its traditions, to which has been added an annual festival that every July commemorates its days of fame. For this year’s edition, the placement of a statue of Clarence Darrow, Scopes’ lawyer, has been announced, in front of his rival Bryan, whose statue was erected in 2005. But the initiative has not received widespread applause from the town and a religious leader has even come to suggest resorting to arms to prevent it.

Javier Yanes for Ventana al Conocimiento

Comments on this publication