In his work Candide, Voltaire ridiculed the idea that everything in our world has been created for the best possible purpose. “Observe that the nose has been formed to bear spectacles, thus we have spectacles,” said his character, Professor Pangloss. This idea, which the French author discussed from the philosophical point of view in the eighteenth century, acquired a scientific significance in the nineteenth when Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace published the theory of natural selection.

According to that first view of biological evolution, all the traits of the species served, like the noses of Pangloss, an advantageous purpose. But in the second half of the twentieth century, the evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould introduced the idea that not everything in evolution appeared for a specific purpose, or that utility could appear later, as with Pangloss’s glasses.

We review five types of traits that today seem useless from the point of view of natural selection, but whose appearance is explained by different mechanisms of evolution.

Vestigial organs: the coccyx

Humans have a tail, although it is not obvious to the naked eye. The coccyx is a small extension of the spine made up of between three and five vertebrae, sometimes fused together. After 15 million years, we have not yet rid ourselves of the remnant of this organ that assists other animals to walk and balance.

Scientists refer to this as vestigiality, the remains of an organ that in another era of our evolution served an end, but no longer. Another example is the erector hair muscle, which in other animals helps to keep them warm but in humans only gives us goose bumps.

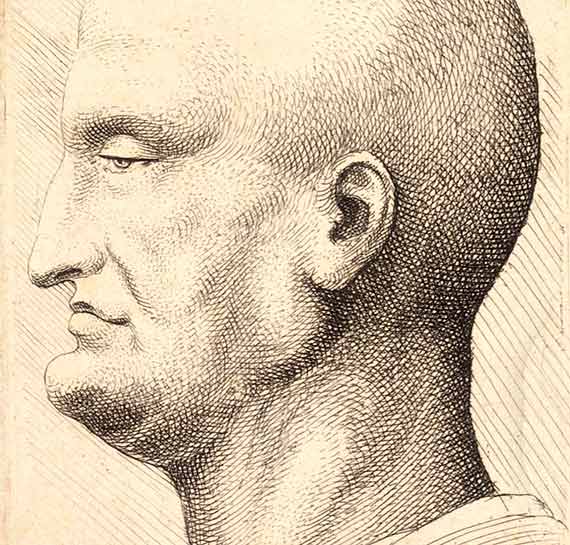

More curious cases are the plica semilunaris and Darwin’s tubercle. The first is a pink fold at the corner of the eye that is the remnant of the third eyelid or nictitating membrane of other species, and the second is a protuberance on the edge of the ear present in some people and which, according to Darwin, is the vestige of the pointy ears of primates.

Vestigial organs abound in nature. Snakes like boas and pythons have spurs in the pelvis, remnants of their former legs. But according to evolutionary biologist David Lahti, vestigiality is a step in evolution towards total loss: “All traits will eventually disappear if they have no function,” he says.

Genetic drift: red hair

Why is red hair so common in Ireland? According to Darwinian theory, the Irish should get some advantage from their hair colour. However, it does not seem to be like that. In the early 1930s, geneticist Sewall Wright proposed that some features do not respond to natural selection, but come from the ancestors who possessed them, without offering any advantage whatsoever. This is known as genetic drift.

The most cited case is the population bottleneck: when a period of harsh conditions decimates a population, the survivors pass on to their offspring traits that are neither advantageous nor unfavourable; simply, they survive and incidentally possessed them. Taken to the extreme, the founder effect is produced, which would explain the abundance of red-haired people on an island like Ireland. The inhabitants of the Pingelap atoll, in Micronesia, do not obtain any advantage from achromatopsia or colour blindness, but come from ancestors who possessed this anomaly.

Genetic hitchhiking: Crohn’s disease

No trait is more useless than the genetic propensity to suffer from diseases. Why, after millions of years of evolution, do we continue to carry these genetic burdens? In 1974, biologists John Maynard Smith and John Haigh observed that sometimes a neutral gene is propagated by being associated with another gene that is favoured by natural selection, to which they applied the term “hitchhiking”: the neutral gene travels on the ticket of the favourable gene. This happens because both are found very close together in the genome. When the advantage is passed on to the offspring, another gene is inherited that may even be harmful.

This may be the case of Crohn’s disease, an intestinal ailment. Patients tend to have a variant of a gene that increases the absorption of a nutrient called ergothioneine. According to one hypothesis, this form would have appeared in the Neolithic period with the development of agriculture, which reduced the amount of ergothioneine in the diet; but inextricably linked to this beneficial gene, other ones spread that are responsible for susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. Similar cases have been proposed for genes related to autoimmune diseases or mental disorders.

Exaptations: laughter

In the same way that humans have found our noses useful for supporting glasses, sometimes evolution has assigned alternative roles to organs that already existed. In 1982, Jay Gould and palaeontologist Elisabeth Vrba coined the term exaptation to refer to this phenomenon.

The most cited case is the plumage of birds. The first feathers appeared in dinosaurs that were unable to fly, so their function was possibly thermal regulation or sexual attraction. Only later did they become an essential tool for flight.

Among the notable examples of exaptation is something that humans use daily, but whose function is still a matter of debate. Some scientists propose that laughter, which emerged in hominids between two and four million years ago as a mechanism of emotional contagion, was later adapted to give it other more complex functions, from serving as part of the conversation to using it for aggressive purposes.

Evolutionary spandrels: the chin

In 1979, Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin wrote an influential essay in which they questioned the absolute supremacy of natural selection. They used as a metaphor the spandrels or pendentives of the dome of the Basilica of San Marcos, in Venice, which seems designed to accommodate the mosaics. Actually it was the opposite—the decoration was adapted to a necessary structural element.

Thus, Jay Gould and Lewontin defined evolutionary spandrels, traits that did not arise by natural selection, but as by-products of others. Spandrels can be exaptative if they adopt a function; for example, human reasoning did not arise to develop theorems. Some scientists argue that the human chin is a spandrel arising from the reduction of the jaws. Another case is the colour of blood: there is no advantage to it being red—it is a consequence of the structure of haemoglobin, necessary to transport oxygen.

Comments on this publication