The science fiction genre exists because its pioneers rightly believed that real, or at least possible, science could be turned into intriguing fictional storylines. These forefathers include authors with scientific or engineering backgrounds, such as H. G. Wells, Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke and Robert Heinlein. The quintessential medium of mass entertainment—the screen—abounds with movies and series that reinvent or simply ignore the laws of science. But it is becoming increasingly common for productions to hire and listen to science consultants. To prove that verisimilitude is no obstacle to imagination, and that popcorn need not be at odds with scientific rigour, here are some examples of quality science in cinema.

Interstellar

Interstellar showed for the first time the depiction of a black hole with Einstein’s general relativity equations. Credit: Paramount/Courtesy Everett Collection/Cordon Press

One of the blockbusters of 2014 owes its success not only to the direction of Christopher Nolan (Inception, The Dark Knight) and the performances of Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway and Michael Caine, but also to the scientific backing and executive production of Nobel Prize-winning physicist Kip Thorne, of the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

Interstellar is set on a future Earth whose resources have been depleted, threatening the survival of humanity. The chance discovery of a wormhole, a theoretical concept in physics capable of linking two distant regions in space-time, gives scientists the opportunity to explore the existence of other habitable planets in the universe. One of the most praised aspects of the movie was the most faithful depiction of a black hole ever achieved on film, a work on which Thorne collaborated with the visual effects team. “This is the first time that the depiction of a black hole begins with Einstein’s general relativity equations,” the physicist said in a promotional video. Five years after the film, the international collaborative project Event Horizon Telescope obtained the first image yof a black hole, roughly confirming what was shown on the screen.

2001: A Space Odyssey

The complex plot of 2001: A Space Odyssey is only fully explained in the book written by Arthur C. Clarke. Credit: Moviepix /Getty Images

When Alfonso Cuarón’s 2013 film Gravity garnered praise for its faithful portrayal of astronaut conditions in space, astrophysicist and science populariser Neil DeGrasse Tyson pointed out that Stanley Kubrick had achieved the same thing 45 years earlier, before the era of manned space stations. The excessive length of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and its complex plot, which is only fully explained in the book written by Arthur C. Clarke and published after the release of the film, weighed on its commercial success at the time. However, Kubrick’s classic has stood the test of time thanks to its realistic depictions of the silence of space, life in microgravity, the creation of artificial gravity, interplanetary travel and communications, and advances in supercomputing. Almost anecdotally, the screens in the film 2001 are flat like today’s, a technology that did not exist at the time and was an accurate prediction that was ignored even in its sequel: 2010. An oft-cited negative criticism is that the film failed to predict the miniaturisation of computers.

Primer

Primer was chosen as one of the best examples of so-called “hard” science fiction, the most rigorous in its scientific approach

In 2004, the director, mathematician and engineer Shane Carruth wrote, produced and directed Primer, a low-budget film about time travel that was chosen as one of the best examples of so-called “hard” science fiction, the most rigorous in its scientific approach. This is despite the fact that the film’s plot, the story of two engineers who inadvertently discover a system for travelling through time, is so complex that it is almost incomprehensible without the help of some diagrams that were circulating on the Internet. One of Carruth’s achievements was to draw inspiration from the ideas of physicist and Nobel laureate Richard Feynman to propose time travel as a turning back of the clock in real time. But Primer also shows the work of researchers in a truthful light, with characters who speak and act like real scientists, and who in some cases arrive at their discoveries almost by chance.

Gattaca

Scientists chose Gattaca as one of the most scientifically sound works of science fiction in cinematic history. Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

At a meeting at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the scientists present chose Gattaca as one of the most scientifically sound works of science fiction in cinematic history. Andrew Niccol’s 1997 film is a dystopian thriller about how genetic engineering in humans and the control of reproductive techniques can lead society towards a system of discrimination based on eugenics, a theme explored by the writer Aldous Huxley in his 1932 novel Brave New World. But this is not the only futuristic classic novel revisited in Gattaca: in the film, the DNA dictatorship culminates in a civilisation ruled with an iron fist through biometric mechanisms, which assume a similar role to the telescreens with which Big Brother, as imagined by George Orwell, controlled the population in 1984.

Contact

Many consider R. Zemeckis’ Contact (1997) de to be the most plausible account of an extra-terrestrial first contact since Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Credit: Sygma via Getty Images

The only novel written by the astrophysicist and science populariser Carl Sagan was made into a film by Robert Zemeckis in 1997, resulting in what many consider to be the most plausible account of an extra-terrestrial first contact since Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977). Sagan poured his knowledge of the real work of SETI (Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence) scientists into his story, and one of them, astronomer Jill Tarter, was actually the model for the main character. Contact is realistic in every respect, from communicating with a distant civilisation via radio and television signals using mathematical language, to the possibility of establishing physical contact using the principle of wormholes, a contribution that Kip Thorne made to Sagan’s novel.

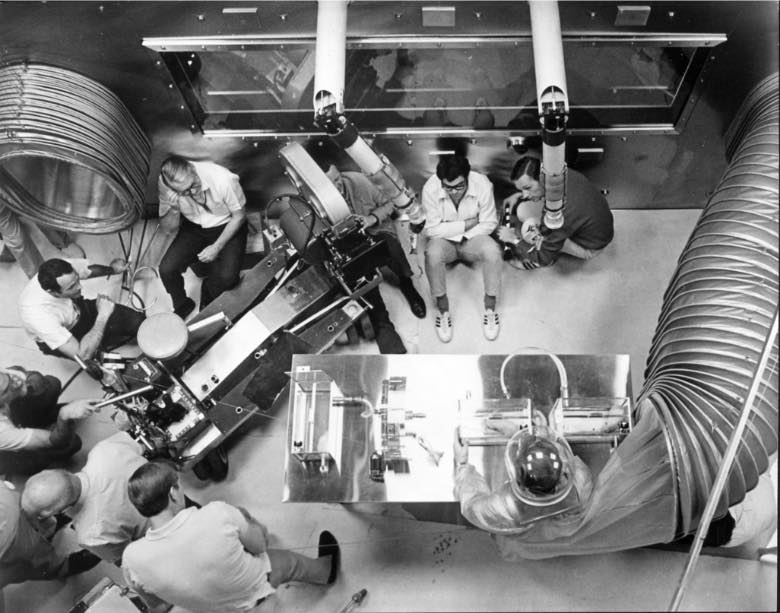

The Andromeda Strain

The Andromeda Strain was filmed by Robert Wise in 1971 from a screenplay based on the novel of the same title that brought fame to Michael Crichton. Credit: Mptv/Cordon Press

The story of a deadly disease plaguing humanity is more topical than ever in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Andromeda Strain was filmed by Robert Wise in 1971 from a screenplay based on the novel of the same title that brought fame to Michael Crichton, author of Jurassic Park. The book was published in 1969, the same year that the world was alarmed by the discovery of a new deadly pathogen, the Lassa virus. In Crichton’s story, the threat comes not from a virus, but from an alien life form that falls to Earth hidden in an old satellite. The plot is reminiscent of dozens of other productions, but few have achieved such a degree of scientific verisimilitude in both form and content. Just as the Martians in War of the Worlds succumbed to terrestrial microbes, the Andromeda life form also has an Achilles’ heel: it can only tolerate a narrow pH (acidity) range, which provides scientists with the key to defeating it.

Contagion

Contagion is the most accurate portrayal of a viral pandemic by a major film studio, which Soderbergh achieved by listening to the advice of scientists. Credit: LILO/SIPA /Cordon Press

While The Andromeda Strain, with all its scientific trappings, is still an alien fantasy, the pandemic fiction that Steven Soderbergh filmed in 2011 was much more relatable. So much so that it now seems less a warning of what might happen than a chronicle of what has already taken place. To this day, Contagion is the most accurate portrayal of a viral pandemic by a major film studio, which Soderbergh achieved by listening to the advice of scientists such as Columbia University epidemiologist Ian Lipkin, who was also a key source of information during the COVID-19 outbreak.

The film even gets certain details right, such as the rise of the conspiracy movement via the Internet. And above all, its very real message about the unsustainability of our relationship with nature is to be applauded: in the film, it is the destruction of a rainforest that causes the pandemic, when a bat carrying the virus takes refuge on a farm and transmits the infection to pigs. Something that, if it hasn’t happened yet, could happen tomorrow.

Don’t Look Up

Director Adam McKay and the story’s co-creator, David Sirota, said the film was an allegory about how we ignore and deny the serious threat of climate change. Credit: Netflix

In recent years, a sub-genre called cli-fi, or climate fiction, has gained momentum, devoted to scientific speculation about climate change and its consequences. So far this century, it has inspired a number of works renowned for their scientific approach, but more in the realm of literature; in film, examples such as The Day After Tomorrow (2004) have proved effective as disaster movies, but with little grounding in real science. In contrast, in 2021, Netflix succeeded in having one of its productions raise public awareness of the risks of climate change, but without mentioning it once in the film.

Directed by Adam McKay, Don’t Look Up is a satirical comedy about two astronomers who discover a comet that will end life on Earth. Instead of terror ensuing, they find that no one takes them or the threat seriously. The film leaves no one untouched, from the powers that be to the media and the public itself, dumbed down by the culture of memes and likes. But there’s no need to look for some contrived metaphorical meaning in all this: from the outset, McKay and the story’s co-creator, David Sirota, said the film was an allegory about how we ignore and deny the serious threat of climate change. Sometimes everything is best understood through metaphor.

The Martian

The self-sustainability of resources is one of the major obstacles to be overcome for the future establishment of bases on the Moon or Mars. Credit: 20thCentFox/Courtesy Everett Collection/Cordon Press

In 2011, novelist and former computer programmer Andy Weir self-published a novel telling the story of a castaway on Mars, whose favourable reception by the public led first to a major publisher, and then to a 2015 film adaptation directed by Ridley Scott. Weir himself researched the scientific and technical details in depth to try to make his story fully credible, and this approach was maintained in the cinematic adaptation, resulting in one of the most acclaimed movies of recent years for its scientific quality.

The most talked about aspect of The Martian was how the castaway character, played by Matt Damon, applied his knowledge of science and botany to grow potatoes in the Martian soil. The self-sustainability of resources is one of the major obstacles to be overcome for the future establishment of bases on the Moon or Mars, and for this reason the hypothesis put forward in the film aroused great interest. However, there are also concessions in The Martian that sacrifice scientific rigour to the needs of narrative or dramatic effect, but that’s fiction.

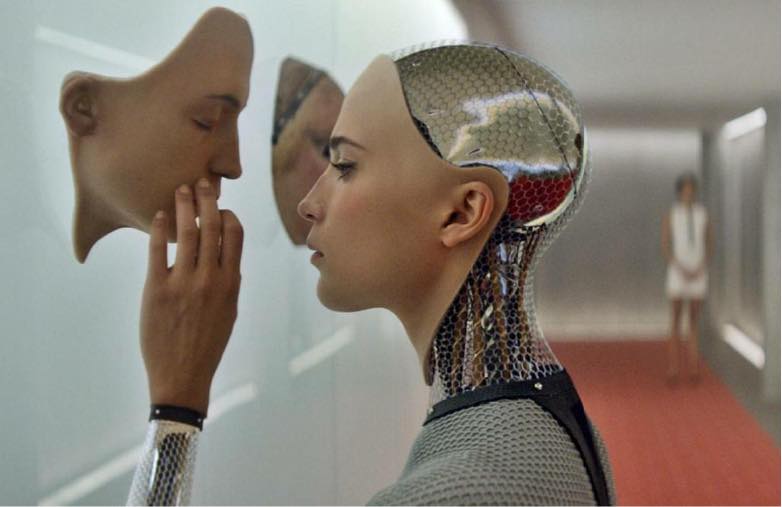

Ex Machina

The rise of tools like ChatGPT, and with the growing concern about the risks of AI, films like Ex Machina take on new significance. Credit: Universal Pictures

Artificial intelligence (AI) has been with us for some time now, and in fiction even longer. A plot about an AI that turns on its creators is perhaps not surprising at this point, since long before the classics that come to mind, there was Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein in 1818. But with the rise of tools like ChatGPT, and with the growing concern of experts themselves about the risks of AI, films like the one Alex Garland made in 2014 take on new significance.

But Ex Machina goes beyond the basic premise of an evil AI pretending not to be evil. The film is full of themes that will emerge as these systems develop in the near future, such as the sexualisation of robots or their ability to become sentient beings. The robot Ava’s success in convincing her examiner that she possesses consciousness is reminiscent of the episode of Google engineer Blake Lemoine, whose LaMDA system managed to fool him in the same way, and foreshadows the rise of this debate in the years to come. This is especially true when the milestone the film depicts has not yet been reached: an AI in a human-like body.

Comments on this publication