Synopsis: Accused of murdering his wife, Andrew Dufresne (Tim Robbins), after being sentenced to life imprisonment, is sent to Shawshank Prison. Over the years he manages to earn the trust of the prison manager and the respect of his fellow prisoners, especially Red (Morgan Freeman), the head of the mafia bribes.

The Shawshank Redemption: an important lesson

There are very few movies which for being deeply human – i.e. real – mark a milestone in cinema history. And not watching them, somehow, entails also being amputated intellectually in order to understand and manage our professional and organizational challenges. This happens with that gem of a movie that grows over time, The Shawshank Redemption, and that I personally place in the Top 100 movies of all time. That is no mean feat.

And among the many issues that the movie touches on, there is one that I consider to be the common thread and makes the most contributions to our business needs: how the success of a change process depends on proper planning, design and management, which we often forget. And this leitmotiv provided by its director, Darabont, with the contrast of two complementary stories: one of a change that fails – the release of the librarian Brooks – and the other, a process that is indeed happily implemented, such as the release of Red (Morgan Freeman) and him finally settling in a Mexican village by the Pacific.

The case of Brooks and the negative perception of change

Remember the scene: Brooks, who has spent over thirty years behind bars in Shawshank, receives the news that the Review Board has granted parole. What appears positive news at first is however received by our protagonist both negatively and aggressively (he tries to stab a fellow inmate). First lesson: not every change we think is positive for our organization or our people will be beneficially perceived by the recipients of that change. Not having this axiom in mind is the cause of the high failure rate of change projects in companies. Those affected by the change will only collaborate with it if there is a positive balance in the subjective cost/benefit analysis.

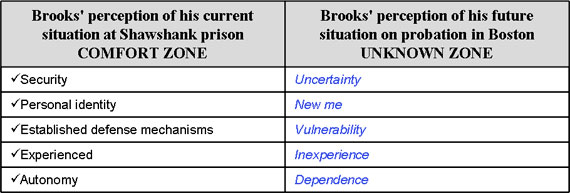

For Brooks, his (apparently irrational) behavior is due to the weight of the negative perceptions and fears of a new civilian life in the city, which we can outline in the following table:

After a little reflection, we realize that Brooks’ new threatening perceptions are the same that currently affect members of any organization – preeminently including banking – before the “future shock” that Alvin Toffler warned about. A shock defined by an amount and intensity of changes – let’s think about digitalization – that create dysfunctional behavior if not managed properly bringing planned transformation projects to a standstill.

But, back to the paradigmatic case of Brooks to describe the barriers and obstacles in more detail that he feels, perceives and based on which acts upon:

- Loss of security: in prison, our librarian “knew what to expect” in terms of procedures, rules, protocol and routines. In his new position, facing the “risk of freedom”, which as Kant saw it, is a sea of uncertainty. He doesn’t know how to cross a street full of cars, he doesn’t know what a traffic light is and has to (unsuccessfully) adapt to a new job. Just like our collaborators facing a technological change, for example, if we do it without planning.

- Loss of his personal identity: in prison, Brooks had a high status “because he was a veteran and due to his role as a librarian”. His social identity was deeply rooted in his primary peer group, with whom he is “institutionalized” within the walls of Shawshank. His new job, assistant cashier at a supermarket, represents a lowering of his professional status. The autonomy which he previously had in managing and handing out books is now crippled by the manager’s supervision.

- Feelings of vulnerability and inexperience: the change in habitat produces a sense of fragility before the unknown. He walks along the street in fear and travels on the bus with his hands tensed up. Too much change in too little time. In his new job there is something preventing him from undertaking it successfully: his arthritic fingers will not let him properly separate paper bags, causing criticism from customers.

- Feeling of dependence: a paradoxical regression to a child/dependent state occurs in Brooks. And the thing is, the human condition is this complex. In prison he had a greater feeling of autonomy than in his new circumstance of freedom. From this infantilization, it will be difficult to maturely resolve the obstacles posed by his release.

The above points explain the failure of change management in our librarian and his tragic final decision. If there is not a plan for change, it is logical that this failure and its protagonists (like Brooks) are unable to overcome the “valley of despair” that involves any loss of a comfort zone. Here we can congruently apply the change curve stages, which has been known well since the early formalizations by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, following the phenomenon of grief, and that Daryl Conner later applied to managing professional and organizational changes.

The question arises from the point: what would have had to be done to make Brooks overcome the 5 stages of “depression” or “valley of despair” and be able to assimilate his new state of freedom?

The answer lies with the movie viewer, comparing the lack of planning and change management of Brooks by the prison authorities with the careful process that Andrew Dufresne (Tim Robbins) unfolds with Red (Morgan Freeman), so he is able to face the release and live in freedom as a purchasing manager at a motel on the west coast of the Mexican Pacific. If we see the movie in this new light, we discover the depth of Dufresne’s leadership and his knowledge of the stages and fears aroused by changes, even if positive, in all of us. As if we very well knew the advantages that a change plan has when buffering and reducing the 5 stages of depression that was insurmountable in the case of Brooks.

Let the intelligent reader/viewer distinguish the careful handling and focus that, from the beginning of the movie, the young broker is applying to a character as seemingly “strong” as Red to assume the change. And draw the appropriate conclusions to adequately deal with the amount of change – and resistance – entailed by the new digital order coming to us. This great and generous movie teaches us all this.

Ignacio García de Leániz Caprile

Consultant / Professor of Human Resources at the University of Alcalá de Henares

Comments on this publication