On almost every important business index, the world is racing ahead. The stakes—the financial, social, environmental, and political consequences—are rising in a similar exponential way.

In this new world, the big question facing business leaders everywhere is how to stay competitive and grow profitably amid this increasing turbulence and disruption. The most fundamental problem is that any company that has made it past the start-up stage is optimized much more for efficiency than for strategic agility—the ability to capitalize on opportunities and dodge threats with speed and assurance. I could give you a hundred examples of companies that, like Borders and Research in Motion (RIM), recognized the need for a big strategic move but couldn’t pull themselves together fast enough to make it and ended up sitting on the sidelines as nimbler competitors beat them, badly.

Companies used to reconsider their basic strategies only rarely, when they were forced to do so by big shifts in their environments. Today any company that isn’t rethinking its direction at least every few years (as well as constantly adjusting to changing contexts) and then quickly making necessary operational changes is putting itself at risk. That’s what faster change is doing to us. But as any business leader can attest, the tension between what it takes to stay ahead of increasingly fierce competition, on the one hand, and needing to deliver this year’s results, on the other, can be overwhelming.

We cannot discount the daily demands of running a company, which traditional hierarchies and managerial processes can still do very well. What they do not do well is identify the most important hazards or opportunities early enough, formulate innovative strategic initiatives nimbly enough, and (especially) execute those initiatives fast enough.

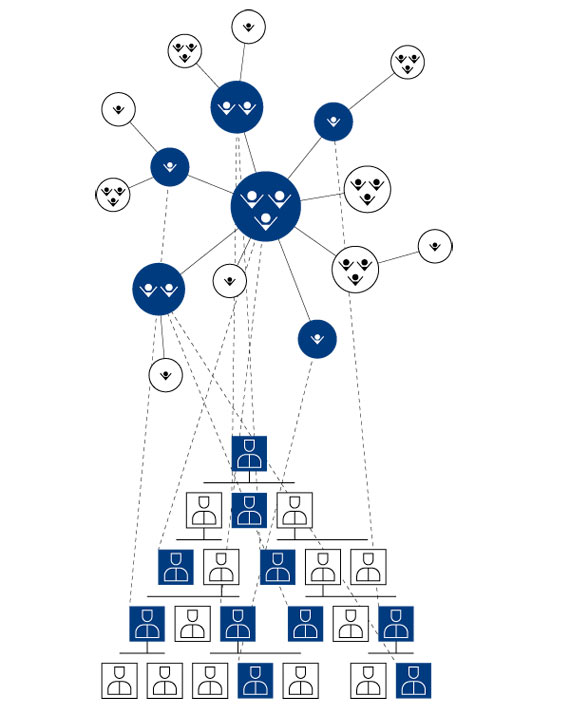

Traditional Management-Driven Hierarchies

Virtually all successful organizations on earth go through a very similar life cycle. They begin with a network-like structure, sort of like a solar system with a sun, planets, moons, and even satellites. Founders are at the center. Others are at various nodes working on different initiatives. Action is opportunity seeking and risk taking, all guided by a vision that people buy into. Energized individuals move quickly and with agility.

The management-driven hierarchies that good organizations use and we take for granted are one of the most amazing innovations of the twentieth century

Over time, a successful organization evolves through a series of stages into an enterprise that is structured as a hierarchy and is driven by well-known managerial processes: planning, budgeting, job defining, staffing, measuring, problem solving. With a well-structured hierarchy and with managerial processes that are driven with skill, this more mature organization can produce incredibly reliable and efficient results on a weekly, quarterly, and annual basis.

A well-designed hierarchy allows us to sort work into departments, product divisions, and regions, where strong expertise is developed and nurtured, time-tested procedures are invented and used, and there are clear reporting relationships and accountability. Couple this with managerial processes that can guide and coordinate the actions of employees—even thousands of employees located around the globe—and you have an operating system that lets people do what they know how to do exceptionally well.

There are those who deride all of this as a bureaucratic leftover from the past, not fit to handle twenty-first-century needs. Get rid of it. Smash it. Start over. Organize as a spider web. Eliminate middle management and let the staff manage themselves. But the truth is that the management-driven hierarchies that good organizations use and we take for granted are one of the most amazing innovations of the twentieth century. And they are still absolutely necessary to make organizations work.

Executives are launching more strategic initiatives than ever. Skilled leaders have always tried to improve productivity, but now they are trying to innovate more and faster

One part of what makes them amazing is that they can be enhanced to deal with change, going beyond mere repetition—at least up to a point. We have learned how to launch initiatives within a hierarchical system to take on new tasks and improve performance on old ones. We know how to identify new problems, find and analyze data in a dynamic marketplace, and build business cases for changing what we make, how we make it, how we sell it, and where we sell it. We’ve learned how to execute these changes by adding task forces, tiger teams, project management departments, and executive sponsors for new initiatives. We can do this while still taking care of the day-to-day work of the organization because this strategic change methodology is easily accommodated by a hierarchical structure and basic managerial processes. And that is precisely what leaders everywhere have been doing, and to a greater degree, each year.

Every relevant survey of executives I have seen for a decade now reports that they are launching more strategic initiatives than ever. Skilled leaders have always tried to improve productivity, but now they are trying to innovate more and faster. When historical organizational cultures—formed over many years or decades— have slowed action, impatient leaders have tried to change those cultures. The goal of all this, of course, is to accelerate profitable growth to keep up or get ahead of the competition.

But those same surveys show that success across these initiatives is often illusive. A recent reboot at JCPenney, for example, looked exceptionally promising—for a few months. And then all the various strategic projects began to fall apart. Even well-run organizations, unless they are very small and new, are having great difficulty moving with the speed and agility required in a faster-moving world. Japanese firms that once were the envy of everyone are now being left in the dust by rivals in Korea and California.

Across industries and sectors, and around the world, everywhere you look it seems clear that the current way in which we run our organizations—even when we enhance them with more and more sophisticated strategic planning departments or interdepartmental task forces—may not be able to do the job.

The Limits of Hierarchies

The frustrations of this reality are well known.

You find yourself going back again and again to the same small number of trusted people to lead key initiatives. That puts obvious limits on what can be done and at what speed. You find that communication across silos does not happen with sufficient speed and effectiveness. You find that policies, rules, and procedures, even sensible ones, become barriers to strategic speed. These inevitably grow over time, implemented as solutions to real problems of cost, quality, or compliance. But in a faster-moving world they become, at a minimum, bumps in the road—if not outright cement barriers.

Going back again and again to the same small number of trusted people to lead key initiatives puts limits on what can be done and at what speed

Part of the problem is political and social: people are often loath to take chances without permission from their superiors. Part of it is simply related to human nature: people cling to their habits and fear loss of power and stature.

Complacency and insufficient buy-in, a typical product of past success, complicate matters further. With even a little complacency, people don’t believe anything much new is needed and begin to resist change. With insufficient buy-in, they might believe something new is needed, but not the strategic initiatives being launched from the top. Both attitudes stall acceleration.

It can be tempting to simply blame the problems on people but the reality is that the problem is systemic and directly related to the limitations of hierarchy and basic managerial processes.

Silos are an inherent part of hierarchical operating systems. They can be made with thinner walls and leaders can try to make them less parochial, but they cannot be eliminated. So too with rules and procedures: we can reduce their number, but we will always need some of them. The list of similar issues goes on and on. You can reduce but not eliminate levels. You can tell people not to ignore the long term but you cannot eliminate quarterly budgets. These and other factors are an inherent part of the system and, predictably, eventually become anchors on efforts to accelerate strategic agility and strategy execution in a faster-moving world.

Good leaders know all these things, if sometimes only intuitively, and try to make up for the problems with those speed-it-up enhancements. They create all sorts of project-management organizations to handle special projects. They use interdepartmental task forces to cut across silos. They bring in strategy consultants or build strategic planning departments to focus on longer-term issues. In a similar way, they add strategic planning to the yearly operational planning exercise. They build in change-management capabilities to overcome complacency, lower resistance, and increase buy-in. When done well, these and other enhancements can reduce the problems with stalling and increase speed and agility— but only up to a point.

Consider typical approaches to change management. Such methods—using diagnostic assessments and analyses, innovative communication techniques, training modules—can be invaluable in helping with episodic problems that have relatively straightforward solutions, such as implementing a well-tested financial reporting system. These approaches are effective when it is reasonably clear that you need to move from point A to point B; when the distance between the two points is not galactic; and when pushback from employees will not be Herculean. Change-management processes supplement the system we know. They can slide easily into a project management organization. They can be made stronger or faster by adding more resources, more sophisticated versions of the same old methods, or more talent to drive the process—but, again, they have their limits.

When it is not 100% clear where point B is because of continuous change, when the jump into the future needs to be a big one because the world is moving so fast, and when the potential pushback is likely to be formidable because of the size of the necessary strategic changes and the potential implications for people, then using a conventional change-management approach may create confusion, resistance, fatigue, and higher costs.

What we need today is a powerful new element to address the challenges posed by mounting complexity and rapid change. The solution, which I have seen work astonishingly well, is a second system that is organized as a network—more like a start-up’s solar system than a mature organization’s Giza pyramid—that can create agility and speed. It powerfully complements rather than overburdens a more mature organization’s hierarchy, thus freeing the latter to do what it’s optimized to do. It makes an enterprise easier to run while accelerating strategic change. This is not a question of “either/or.” It’s “both/and”: two systems that operate in concert. A dual operating system.

The Structure of a Dual System

It seems like new management tools are proposed every week for finding a competitive advantage or dealing with twenty-first-century demands. How is a dual operating system any different? The answer is twofold. First, a dual system is more about leading strategic initiatives to capitalize on Big Opportunities or dodge big threats than it is about management. Second, although the dual system is a new idea, it is a manner of operating that has been hiding in plain sight for years. All successful organizations operate more or less as I describe during the most dynamic growth period in their life cycle. They just don’t understand this while it is happening or sustain it as they mature.

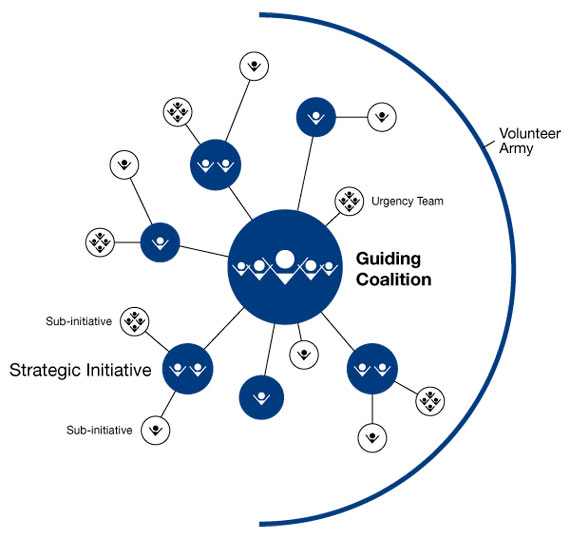

The basic structure is self-explanatory: hierarchy on one side and network on the other. The network side mimics successful enterprises in their entrepreneurial phase, before there were organization charts showing reporting relationships, before there were formal job descriptions and status levels. That structure looks roughly like a constantly evolving solar system, with a guiding mechanism as the sun, strategic initiatives as planets, and sub-initiatives as moons or satellites.

This structure is dynamic: initiatives and sub-initiatives coalesce and disband as needed. Although a typical hierarchy tends not to change much from year to year, this type of network typically morphs all the time and with ease. Since it contains no bureaucratic layers, command-and-control prohibitions, or Six Sigma processes, the network permits a level of individualism, creativity, and innovation that even the least bureaucratic hierarchy, run by the most talented executives, simply cannot provide. Populated with a diagonal slice of employees from all across the organization and up and down its ranks, the network liberates information from silos and hierarchical layers and enables it to flow with far greater freedom and at accelerated speed.

The hierarchy part of the dual operating system differs from other hierarchies in that much of the work ordinarily assigned to it has been shifted over to the network part

The hierarchy part of the dual operating system differs from almost every other hierarchy today in one very important way. Much of the work ordinarily assigned to it that demands innovation, agility, difficult change, and big strategic initiatives executed quickly— challenges dumped on work streams, tiger teams, or strategy departments—has been shifted over to the network part. That leaves the hierarchy less encumbered and better able to perform what it is designed for: doing today’s job well, making incremental changes to further improve efficiency, and handling those strategic initiatives that help a company deal with predictable adjustments, such as routine IT upgrades.

In a truly reliable, efficient, agile, and fast enterprise, the network meshes with the more traditional structure; it is not some sort of “super task force” that reports to some level in the hierarchy. It is seamlessly connected to and coordinated with the hierarchy in a number of ways, chiefly through the people who populate both systems. Still, the organization’s top management plays a crucial role in starting and maintaining the network. The C-suite or executive committee must launch it, explicitly bless it, support it, and ensure that it and the hierarchy stay aligned. The hierarchy’s leadership team must serve as role models for their subordinates in interacting with the network. I have found that none of this requires much C-suite time. But these actions by senior executives clearly signal that the network is not in any way a rogue operation. It is not an informal organization. It is not just a small engagement exercise which makes those who participate feel good. It is part of a system designed for competing and winning.

The Dual System

Evolution of the Company: From Network to Hierarchy

I am not describing a purely theoretical idea. Every successful organization goes through a phase, usually very early in its history, in which it actually operates with this dual structure. This is true whether you are Panasonic in Osaka, Morgan Stanley in New York, or a nonprofit in London. The problem is that the network side of a dual system in the normal life cycle of organizations is informal and invisible to most people, so it rarely sustains itself. As they mature, organizations evolve naturally toward a single system—a hierarchical organization—at the expense of the entrepreneurial network. The lack of insight and effort to formalize and sustain an organization that was both highly reliable and efficient on the one hand and fast and agile on the other did not cost us much in a slower-moving past. That situation has changed forever—for Panasonic, Morgan Stanley, and thousands of others— or it will soon.

Characteristics of the Dual Operating System

On close observation, it’s clear that a well-functioning dual operating system is guided by a few basic principles:

- Many people driving important change, and from everywhere, not just the usual few appointees. It all starts here. For speed and agility, you need a fundamentally different way to gather information, make decisions, and implement decisions that have some strategic significance. You need more eyes to see, more brains to think, and more legs to act in order to accelerate. You need additional people with their own particular windows on the world and with their additional good working relationships with others, in order to truly innovate. More people need to be able to have the latitude to initiate—not just carry out someone else’s directives. But this must be done with proven processes that do not risk chaos, create destructive conflict, duplicate efforts, or waste money. And it must be done with insiders. Two hundred consultants, no matter how smart or dynamic, cannot do the job.

- A “get-to” mindset, not a “have-to” one. Every great leader throughout history has demonstrated that it is possible to find many change agents, and from every corner of society—but only if people are given a choice and feel they truly have permission to step forward and act. The desire to work with others for an important and exciting shared purpose, and the realistic possibility of doing so, are key. They always have been. And people who feel they have the privilege of being involved in an important activity have also shown, throughout history, that they will volunteer to do so in addition to their normal activities. You don’t have to hire a new crew at great expense. Existing people provide the energy.

- Action that is head and heart driven, not just head driven. Most people won’t want to help if you appeal only to logic, with numbers and business cases. You must also appeal to how people feel. As have all the great leaders throughout history, you must speak to the genuine and fundamental human desire to contribute to some bigger cause, to take a community or an organization into a better future. If you can provide a vehicle that can give greater meaning and purpose to their efforts, amazing things are possible.

- Much more leadership, not just more management. To achieve any significant though routine task—as well as the uncountable number of repetitive tasks in an organization of even modest size—competent management from significant numbers of people is essential. Yes, you need leadership too, but the guts of the engine are managerial processes. Yet in order to capitalize on unpredictable windows of opportunity which might open and close quickly, and to somehow spot and avoid unpredictable threats, the name of the game is leadership, and not from one larger-than-life executive. The game is about vision, opportunity, agility, inspired action, passion, innovation, and celebration—not just project management, budget reviews, reporting relationships, compensation, and accountability to a plan. Both sets of actions are crucial, but the latter alone will not guarantee success in a turbulent world.

- An inseparable partnership between the hierarchy and the network, not just an enhanced hierarchy. The two systems, network and hierarchy, work as one, with a constant flow of information and activity between them—an approach that succeeds in part because the people essentially volunteering to work in the network already have jobs within the hierarchy. The dual operating system cannot be, and does not have to be, two super-silos, staffed by two different groups of full-time people, like the old Xerox PARC (an amazing strategic innovation machine) and Xerox corporate itself (which pretty much ignored PARC, or at least could never execute on the fantastic commercial opportunities it uncovered). And, ultimately, the meshing of the two parts succeeds as does anything new that at first seems awkward, wrong, or threatening: through education, role modeling from the top of the hierarchy, demonstrated success, and finally sinking into the very DNA of the organization, so it comes to feel just like, well, “the way we do things here.”

These principles point to something very different than the default way of operating within a hierarchy: to drive change through a limited number of appointed people who are given a business case for a particular set of goals and who project-manage the process of achieving the goals in the case. That default process can work just fine when the pace needed is not bullet-like, the potential pushback from people is not ferocious, and the clarity of what is needed is high (and innovation requirements are therefore low). But, increasingly, that is not the world in which we are living.

Based on these principles, the action on the network side of a dual system is different from that on the hierarchy side. Both are systematic. They are just very different. It’s not a matter of one side being hard and metrically driven while the other is fluffy or soft. We know less today about network processes like “creating short-term wins” than we do about hierarchical processes like operational planning or creating relevant metrics. But, just as action within a well-run hierarchy is far from control-oriented people doing whatever comes into their heads, action within a well-run network is very different from enthusiastic volunteers doing whatever they want.

Because action within networks accelerates activity, especially strategically relevant activity, I call its basic processes the Accelerators.

The Eight Accelerators

The network’s processes resemble the activity you usually find in successful, entrepreneurial contexts. They are much like my eight steps for leading change, only this time with top management launching a dynamic that creates many more active change drivers, a network structure integrated with the hierarchy, and processes that, once started, never stop.

These are the eight Accelerators:

- Create a Sense of Urgency Around a Big Opportunity

The first Accelerator is all about creating and maintaining a strong sense of urgency, among as many people as possible, around a Big Opportunity an organization is facing. Building a dual system starts here. This is, in many ways, the secret sauce which allows behavior to happen that many who have grown up in mature organizations would think impossible.

Urgency, in the sense used here, is not just about this week’s problems but about the strategic threats and possibilities flying at you faster and faster. With Accelerator 1 working well, large groups of people, not just a few executives, rise each day thinking about how they might be able to help you pursue a Big Opportunity.

- Build and Evolve a Guiding Coalition

The second Accelerator leverages off a greatly heightened and aligned sense of urgency to build the core of the network structure, then later to help it evolve into a stronger and more sophisticated form. This guiding coalition of people from across the organization feels the urgency deeply. These are individuals from all silos and levels who want to help you take on strategic challenges, deal with hyper-competitiveness, and win the Big Opportunity. They are people who want to lead, to be change agents, and to help others do the same. This core group has the drive, the intellectual and emotional commitment, the connections, the skills, and the information to be an effective sun in your dynamic new solar system. These are people who can, and do, learn how to work together effectively as a large team.

With a sufficient sense of urgency, finding good people who want to participate in a guiding coalition is surprisingly easy. Getting individuals from different levels and silos to work well together requires effort. Just throw them into a room and they are likely to recreate what they know: a management-centric hierarchy. But under the right conditions—with urgency around a Big Opportunity as a crucial component—they will learn how to work together in a totally new way. And with help, both the guiding coalition and the organization’s executive committee will learn how to work together in a way that allows for the hierarchy side and the network side to stay strategically aligned, to maintain high levels of reliability and efficiency, and to develop a whole new capacity for speed and agility.

- Form a Change Vision and Strategic Initiatives

The third Accelerator has the guiding coalition clarify a vision that fits a big strategic opportunity and select strategic initiatives that can move you with speed and agility toward the vision. When you first form a dual system, much of this, especially the initiatives, may already exist, created by the hierarchy’s leadership team. But the initiatives the nascent network side attacks first will be those that individuals in the guiding coalition have great passion to work on. These will always be activities that the organization’s executive committee agrees make great sense. But these will be initiatives which a management-driven hierarchy is ill-equipped to handle well enough or fast enough by itself.

- Enlist a Volunteer Army

In the fourth Accelerator, the guiding coalition, and others who wish to help, communicate information about the strategic vision and the strategic change initiatives to the organization in ways that lead large numbers of people to buy into the whole flow of action. Done well, this process results in many individuals wanting to help, either with some specific initiative or just in general. This Accelerator starts to pull, as if by gravity, the planets and moons into the new network system.

- Enable Action by Removing Barriers

In the fifth Accelerator, everyone helping on the network side (the “right side” in the illustrations) works swiftly to achieve initiatives and find new ones that are strategically relevant. People talk, think, invent, and test, all in the spirit of an agile and swift entrepreneurial start-up. Much of the action here has to do with identifying and removing barriers which slow or stop strategically important activity. Within a dual system, and unlike in a start-up, this process guides people to pay close attention to their hierarchy: to what is being done there (to avoid overlap of effort), to what has been done there (to avoid plowing old ground), and to the hierarchy’s operational goals and incremental strategic initiatives (to maintain alignment). Smart actions, based on good information from all silos and levels, are taken with heightened speed.

- Generate (and Celebrate) Short-Term Wins

The sixth Accelerator is about everyone on the network side helping to create an ongoing flow of strategically relevant wins, both big and very small. Action here also ensures that the wins are as visible as possible to the entire organization and that they are celebrated, even if only in small ways. These wins, and their celebration, can carry great psychological power and play a crucial role in building and sustaining a dual system. They give credibility to the new structure. This credibility in turn promotes more and more cooperation within the overall organization. These wins draw out respect, understanding, and eventually complete cooperation from the most control-oriented managers, who themselves have no desire to be network-side volunteers.

- Sustain Acceleration

Accelerator 7 keeps the entire system moving despite a general human tendency to let up after a win or two. It is built on the recognition that so many wins come from sub-initiatives which, by themselves, may be neither substantial nor particularly useful in a strategic sense. Larger initiatives will lose steam and support unless related sub-initiatives are also completed successfully. Here, with relentless energy focused forward on new opportunities and challenges, we find a motor which helps all the others. Accelerators keep going, as needed, like spark plugs and cylinders in a car’s engine. It is the opposite of a one-and-done approach and mindset.

- Institute Change

Accelerator 8 helps institutionalize wins, integrating them into the hierarchy’s processes, systems, procedures, and behavior— in effect, helping to infuse the changes into the culture of the organization. When this happens with more and more changes, there is a cumulative effect. After a few years, such institutionalizations of action drive the whole dual operating system approach into an organization’s very DNA.

When these Accelerators are all functioning well, they naturally solve the challenges inherent in building a new and different kind of organization. They provide the energy, the volunteers, the coordination, the integration of hierarchy and network, and the needed cooperation. As they capitalize on opportunities and work around threats, the whole system grows and accelerates. Eventually it becomes the way you do business in a rapidly changing world. You move ahead of tough competition or achieve fiercely ambitious goals. And, done right, all this happens without adding expensive staff, disrupting daily operations, or missing earnings targets.

The Eight Accelerators

The Volunteer Army

The people who drive these processes and populate the Accelerator network also help make the daily business of the organization hum. They’re not a separate group of consultants, new hires, or task force appointees.

We have found that a guiding coalition of 5–10% of the managerial and employee population in a hierarchy is typically an appropriate size. A team of this size is generally large enough to make the dual system work, for two reasons. First, because they work in the hierarchy, these 5–10% have crucial organizational knowledge, relationships, credibility, and influence. They are often the first to see threats or opportunities—and they have the zeal to deal with them if put into a structure where that is possible. Second, they add no new (perhaps impossibly large) budget item.

A guiding coalition of 5–10% of the managerial and employee population in a hierarchy is typically an appropriate size. A team of this size is generally large enough to make the dual system work

If the sense of urgency around the Big Opportunity is high enough, a guiding coalition of this size will have a large enough reach into the organization to recruit their colleagues to volunteer on initiatives and subinitiatives, thereby growing the network. In a fully functioning dual operating system, it is not unusual to see more than half of an organization volunteering in some capacity to drive transformational change. Modest but aligned actions, taken by many passionate people who bring with them insight from all levels and all silos, imbue the network with the power it needs to undertake smart, strategic action.

People who have never seen this sort of dual operating system work often worry, quite logically, that a bunch of enthusiastic volunteers might create more problems than they solve—by running off and making ill-conceived decisions and disrupting daily operations. Here is where the network structure, the underlying principles, and the accelerating processes all come into play. They create conditions under which people generate not just ideas, but ideas backed by good data from all silos and levels in a hierarchy. They create conditions under which people do not just develop initiatives, but understand that it is their job to implement them. They create conditions which guide people not just to keep daily operations running smoothly, but also to improve day-to-day processes to make the work of the organization easier, more efficient, less costly, and more effective.

The Role of the Guiding Coalition

In organizations where a dual system has really taken hold, individuals have told me that the rewards from working in the network can be tremendous—though they are rarely monetary. They talk about the fulfillment they get from pursuing a broader, enterprise-wide mission they believe in. They appreciate the chance to collaborate with a broader array of people than they ever could have worked with in their regular jobs within the hierarchy. A number of them say that their strategy work has led to increased visibility across the organization and to better positions in the hierarchy. And their managers often come to appreciate how the volunteers develop professionally. Consider this email I received from a client in Europe: “I can’t believe how quickly this second operating system gives growth to real talents within the organization. Once people feel ‘Yes, I can do it!’ they also start faster growth in their regular jobs in the hierarchy, which helps make today’s operations more effective.”

Growing and Building Momentum Organically

A dual operating system doesn’t start fully formed and doesn’t require a sweeping overhaul of the organization—hence there is much less risk than one might think. It evolves, growing organically over time, accelerating action to deal with a hyper-competitive world, and taking on a life that seems to differ in the details from company to company. It can start with small steps. Version 1.0 of a right-side, strategy-accelerator network may arise in only one part of an enterprise—say, the supply chain system or the European group. After it becomes a powerful force there, it can expand into other parts of the organization.

In a fully functioning dual operating system, it is not unusual to see more than half of an organization volunteering in some capacity to drive transformational change

Version 1.0 may also play no role in strategy formulation or adjustment, but concentrate only on agile and innovative implementation. It may feel at first more like a big employee-engagement exercise hat, indeed, produces a much bigger payoff without increasing the payroll. But the network and the Accelerators evolve, and momentum comes faster than you might expect. As long as the executive committee understands the new system and plays its role, and as long as the new organization does indeed help with competitive challenges, the whole dual system model will eventually seep into the culture as “the way we do things here.”

Not surprisingly, there are challenges. Over the past seven years, my team has aided any number of pioneers—in the private and public sectors, functional departments, product divisions, or at corporate headquarters—in building dual operating systems. The challenges are fairly predictable, and not insignificant. One is ensuring that the two parts of the system learn to work together well. Here it is essential that the core of the network (the guiding coalition) and the executive committee learn to develop and maintain the right relationship. Another is building momentum: the most important step here is to create and communicate wins from the very start.

Probably the biggest challenge is how to make people who are accustomed to control-oriented hierarchies believe that a dual system is even possible. Education can help. The right attitude from the top of the hierarchy helps greatly. But again, this is why a rational and compelling sense of urgency around a big strategic opportunity is so important. Once it has been sparked, mobilizing the guiding coalition and putting the remaining Accelerators in motion can happen almost organically. It doesn’t jolt an enterprise the way sudden dramatic organizational change does. It doesn’t require you to build something gigantic and then flick a switch to get it going (while praying that it works). And in a world where capital is constrained in so many organizations, the incremental cost of this approach is, incredibly, almost nothing. Think of it as a vast, inexpensive, purposeful, and structured expansion—in scale, scope, and power—of the smaller, informal networks that accomplish important tasks faster and cheaper than hierarchies can.

Conclusion

The inevitable failures of single operating systems hurt us now. I believe they are going to kill us in the future. The twenty-first century will force us all to evolve toward a fundamentally new form of organization. The good news is that this can allow us to do much more than simply hang onto what we have achieved in the twentieth century. If we successfully implement a new way of running organizations we can take advantage of the strategic challenges in a rapidly changing world. We can actually make better products and services, enlarge wealth, and create more and better jobs, all more quickly than we have done in the past. That is, while the consequences of an increasingly changing world do have a downside, they also have a potentially huge upside.

We still have much to learn. Nevertheless, the companies that get there first, because they are willing to pioneer action now, will see immediate and long-term success—for shareholders, customers, employees, and themselves. I am convinced that those who lag will suffer greatly—if they survive at all.

Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review Press. Adapted from John P. Kotter, Accelerate: Building Strategic Agility for a Faster-Moving World (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2014). All rights reserved.

Comments on this publication