In the past 30 years, religion has returned to global politics. Disputes over religious issues, ranging from abortion, to same-sex marriage, to the wearing of headscarves in schools, have become major areas of contention across Western democracies. Religious parties and movements have made striking electoral breakthroughs in countries such as India, Egypt, Turkey, and Israel, and established theocratic government in countries such as Iran and Afghanistan. The apparent return of religion has led some commentators to view theological fissures as predictors of international, as well as domestic conflict, with nations aligning into “civilizational blocs” that mirror the world’s major faiths (1) (Huntington 1996).

Why have religious identities and values achieved such renewed prominence in the early 21st Century? One theory is that the return of religion reflects “de-” or “counter-” secularization, as individuals have returned to religious ritual and discourse as a means of navigating the complexities of modern life (Berger 2005). The rise of Evangelical Christianity in Latin America, Korea, and the United States, the reopening of Orthodox and Catholic churches in the former Communist bloc, and the growth of Islamist movements in the Middle East are all taken as evidence of this trend. As Huntington writes, “the religious resurgence involved people returning to, reinvigorating, and giving new meaning to the traditional religions of their communities” (Huntington 1996: 96).

In this chapter we advance an alternative view, which is that religious and moral issues have become steadily more contentious as a result of the decline of religious authority and values in the developed world. Since the 1960s, adherence to traditional religious values has fallen sharply across Europe and North America, giving rise to a new set of norms based on individual freedom and self-expression, including acceptance of abortion and divorce, tolerance of homosexuality, and more progressive attitudes to women’s rights. As these views have become increasingly mainstream, they have led to legislative changes such as same-sex marriage, abortion on demand, and state-provided childcare. Such changes have provoked frustrated responses by socially conservative groups, such as the pro-life movement in the United States, Ireland, and Spain, as well as immigrant communities with conservative values in countries like France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

In the developing world, by contrast, religious parties and movements such as Hindutva in India, the Justice and Development Party in Turkey, and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt have achieved genuine mass support. Following Kepel (1994) and Casanova (1994), we explain the rise of religious parties and movements in the developing world as the result of a process of social mobilization, in which previously passive citizens are transformed into democratic actors through a political discourse rooted in popular notions of religious faith and significance. As new movements have sought to challenge the secular liberal and nationalist elites that guided these countries through their post-independence era, religious discourse has functioned as a means of engaging with new urban social groups. However, against the “counter-secularization” hypothesis, we find no evidence of any increase in religious identification, even in developing countries. The growth of religious movements is not a result of changing mass beliefs and values, but rather a consequence of the entry of the masses into political life in countries where power was previously monopolized by secular elites. As such, it may be followed by a similar decline in mass religious observance and values in future years, under similar circumstances of affluence to those prevailing in late twentieth-century Europe, Australasia, and Northern America.

The Decline of Religion and the Rise of Secular Values in the Western World

Evidence concerning religious values, beliefs and behavior can be drawn from the World Values Surveys and European Values Study, a global investigation of socio-cultural and political change. This project has carried out representative national surveys of the basic values and beliefs of the publics in 92 nation states, containing in total over 6 billion people or 90% of the world’s population and covering all six inhabited continents. It builds on the European Values Surveys, first carried out in 22 countries in 1981: a second wave of surveys, in 41 nations, was completed in 1990–91, a third wave of 55 nations in 1995–6, a fourth wave of 59 nations in 1999–2001, and a fifth wave of 57 nations in 2005–7. The World Values Surveys include some of the most affluent economies in the world, such as the US, Japan, and Switzerland, with per capita incomes as high as $45,000; middle-income industrializing countries such as South Korea, Brazil, and Turkey, with per capita incomes between $10,000 and $20,000, and poorer agrarian societies, such as Rwanda, Bangladesh, and Vietnam, with per capita incomes of $400 or less. The most comprehensive coverage of the survey is in Western Europe and North America, where public opinion surveys have the longest tradition, but countries are included from all world regions, including many Sub-Saharan African nations. The survey also includes the first systematic data on public opinion in many Muslim states, including Arab countries such as Jordan, Egypt, and Morocco, as well as in Indonesia, Iran, Turkey, and Pakistan.

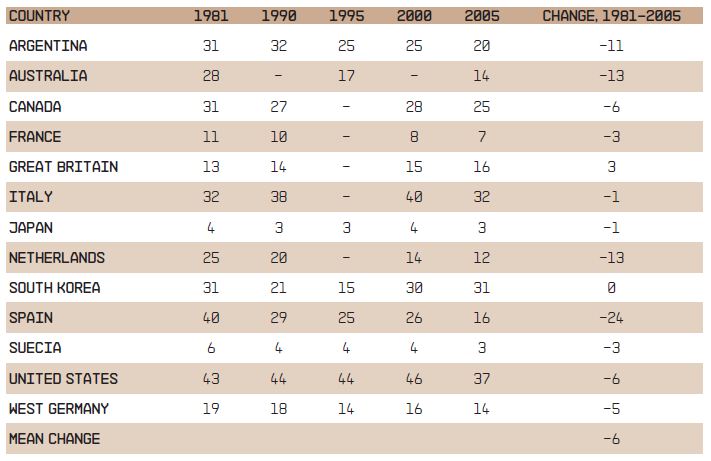

Since 1981, the World Values Survey has asked respondents how frequently they attend church, mosque, or temple services, ranging from once a year, to specific holidays, to once a month, to once a week, to more often than this. Table 1 shows the proportion attending religious services at least once a week across 13 industrial and post-industrial countries included in both the 1981 and the 2005–7 waves of the WVS, and the results demonstrate the steady decline of religious practice and belief across Western countries in the late twentieth century.

Table 1: Frequency of Attending Religious Services at Least “Once A Week”. Source: World Values Surveys and European Values Study, 1981–2007.

Strong falls in churchgoing are evident across Western Europe, particularly in Spain, the Netherlands, and Germany. Japan, Sweden, and France saw falls in religious attendance from already low levels, so that by 2005 figures for weekly participation had fallen to single digits, while moderate declines can be seen in the United States, Canada, and Germany. Only in South Korea and Great Britain were levels of attendance higher in 2005 than in 1981, though in both cases only by a small amount.

As organized religion has lost its authority over people’s lives and behavior, there has been a corresponding shift in attitudes towards religious or moral issues, including attitudes towards abortion, homosexuality, divorce, and the role of women in society. Since 1981, the World Values Surveys have asked respondents to rate their opinion towards a range of moral acts and lifestyle choices, ranging from 1 (never justifiable) to 10 (always justifiable). In 1981, 30% of respondents in Western Europe and 43% of Americans responded that abortion was “never” justifiable; by 2005 these had fallen to 19% and 26%, respectively. In 1981, almost half (48%) of Western Europeans and two-thirds (64%) of Americans expressed a view that prostitution is “never justifiable”; by 2005 these were just a third (33%) and two-fifths (43%).

Table 2: Percentage of the Population Saying Selected Acts are “Never” Justifiable. Source: World Values Survey y European

Values Study, 1981–2007.

A more comprehensive overview of these value shifts can be gained from Table 2, which shows the full results for the percentage of respondents for whom abortion, homosexuality, divorce, and prostitution are “never” justifiable across the full 13 industrial and post-industrial societies for which data spans the full range from 1981 to the present day. The surveys show marked declines in Sweden, Spain, France, Germany, and Argentina, with steady falls also evident in other countries. In every country, attitudes to divorce became more accepting, and in every country but one (Japan) attitudes became more tolerant of prostitution. Large shifts also occurred in attitudes to homosexuality, such that by 2005 extreme homophobic sentiment was a minority view in almost every country including Argentina, South Korea, and the United States. Finally, unconditional opposition to abortion fell in every country except Argentina and Italy, such that in almost all countries a majority could conceive of circumstances where abortion would be permissible.

As moral attitudes and beliefs have become more progressive, there has also been a steady movement in the policy arena towards more legal reform in areas such as divorce, abortion, prostitution, and same-sex marriage. Among the first areas of amendment were marriage and divorce laws, which remained restrictive across southern Europe until the late twentieth century, but were liberalized in Italy in 1970, Portugal in 1975, Spain in 1981, and Ireland in 1997. A second area is abortion, which is strongly censured by the Catholic, Orthodox, and most Protestant churches, yet was legalized in Great Britain in 1967, the United States in 1973, France in 1975, and Italy in 1978. A third area is prostitution, which since being banned in many countries during the nineteenth century, has been decriminalized and regulated in Australia since 1992, in Denmark since 1999, in the Netherlands since 2000 (2), in New Zealand since 2003, as well as Germany, Switzerland, Turkey, and the US state of Nevada. Capital punishment has been outlawed in phases across most Western countries, with a freeze on executions giving way to a comprehensive legal prohibition across the European Union (3). And finally, same-sex marriages have been given full legal recognition across a number of Western countries, beginning with the Netherlands in 2003, followed by Spain and Canada in 2005, and Sweden in 2009 (4).

Western societies have therefore undergone an uneven process of societal liberalization since the 1970s that has encompassed sexual, reproductive, and lifestyle freedoms. While elites such as judges and parliamentarians have often been the initiators of legislative change, these reforms have largely been supported by mass beliefs and values. There is no better reflection of this than the fact that changes to the law have often been confirmed through popular referenda, as was the case with divorce law in Ireland, civil unions in Switzerland, or abortion in Portugal. Moreover, there have been remarkably few instances of policy reversal, and several cases where referenda intended to roll back a parliamentary law were defeated at the ballot box (for example Italy regarding divorce law in 1974, Switzerland concerning abortion in 1978 and 1985).

Concurrent with the widened acceptance of liberal attitudes regarding lifestyle choices, there has also been a consolidation of secular norms regarding politicians and public life. The separation of religion from politics is the defining attribute of the secular state, and in both the 2000 and the 2005 Values Surveys, representative samples of the public were asked regarding their extent of agreement with the statement that “religious leaders should not influence the government.” In the countries of the European Union, on average 70% of respondents agreed with this view, including 76% of Swedes, 85% of Danes, and 82% of French. The widening acceptance of secular norms has led to corresponding institutional changes, in particular the reform of blasphemy legislation, and the disestablishment of the church. The majority of European countries have now removed their state religion, for example Spain where the Roman Catholic Church remained the official faith until 1978; Italy, where this was true until 1984; and Sweden, which though a largely secular society, only disestablished the Lutheran church in 2000. In the United Kingdom, where the Church of England remains the established church, blasphemy laws were officially abolished in 2008, following previous reform through the Criminal Justice Act of 1967 (which legalized profanity) and the 1998 Human Rights Act (5). In the Netherlands the government is currently considering repealing its blasphemy laws, though these have not been applied since the 1960s; in most other European countries blasphemy laws remain on the books, but are similarly disregarded by the courts or directly contradicted by free speech legislation. A case brought against the Danish author of the Mohammed cartoons, for example, was rejected on grounds of freedom of expression (6). Finally, in most European countries religious leaders have no consultative role in government, as has been the case in centuries past. In one last exception to this rule, the United Kingdom, there are 26 bishops who continue to sit in the House of Lords, though the House of Commons has voted in favor of abolishing all unelected members and faces resistance only from the Lords itself.

At the same time as religion has lost its privileged position within the state, and its corresponding legal protections, Western societies have incorporated immigrant groups for whom the public expression of religious identity, the ability to educate children religiously, and maintain practices such as arranged marriage, remain very important. The response has been an attempt to “fit” such newcomers into the mould of the secular system: for example, by banning wearing of the hijab, a form of Islamic dress, which was prohibited along with other displays of religious identity in French schools in 2004, as well as being restricted in eight German states and several Belgian municipalities; by banning forced marriage, as occurred in Norway in 2003 and Belgium in 2006; or by instituting “civic education” classes of the kind now required of new Dutch citizens. Such moves have typically provoked resistance and resentment among conservative migrants, who view them as an indignity and an encroachment on their cultural rights. However, where the demands of a secular liberal society to protect individual rights and freedoms conflict with cultural practices that infringe such norms and obligations, there is an irresolvable dilemma.

Just such an important value conflict is highlighted by the European Values Surveys of 2000, in which members of the public in six countries were asked whether they would be in favor of restricting publications that offend religious sensibilities, or whether they would uphold freedom of speech. This is an issue that has become highly sensitive in recent years following the assassination in the Netherlands on religious grounds of Theo van Gogh in 2004, the Danish cartoon crisis of 2005, and the passing in 2006 of an incitement to religious hatred law in the United Kingdom. The results shed light on an important aspect of the dynamics between religious traditionalists and secular liberals. In every country, a majority spoke out against such a ban, and in favor of freedom of speech, yet among the sub-sample who identified as “religious,” the majority was in favor in four of the six countries. Notably, support for a ban was also the majority option among Muslim respondents. There is therefore a fundamental value difference between religious and non-religious respondents, reflecting the clash between the new value consensus of Western societies, and the traditional values and beliefs of minorities and religious conservatives.

Sacred and Secular: the Role of Religious Mobilization

If a secular-liberal consensus appears to have taken hold in Western democracies, many would argue that such values are in retreat in the developing world. Since the 1970s religious parties have risen to prominence in Turkey, India, and many Arab countries, while theocratic regimes have been established in Iran and in Afghanistan. Several countries have introduced religious provisions to their constitutions, such as Pakistan, which established Islam as the state religion in 1973, and Bangladesh, whose parliament amended the constitution to make Islam the state religion in 1988. These amendments have had widespread legal ramifications, in particular where they have brought the introduction of Shari’a provisions outlawing blasphemy, punishing adultery by stoning, and establishing fixed penalties (such as hand amputation) for a range of petty crimes. In addition to legal changes, there has been a rising tide against Western culture across the Middle East and South Asia. Young women in Arab universities and cafes can be seen making increasing use of the hijab, while public commentators in the Arab press openly call for struggle against Western culture, media, and entertainment (Dale 2003; Najjar 2005).

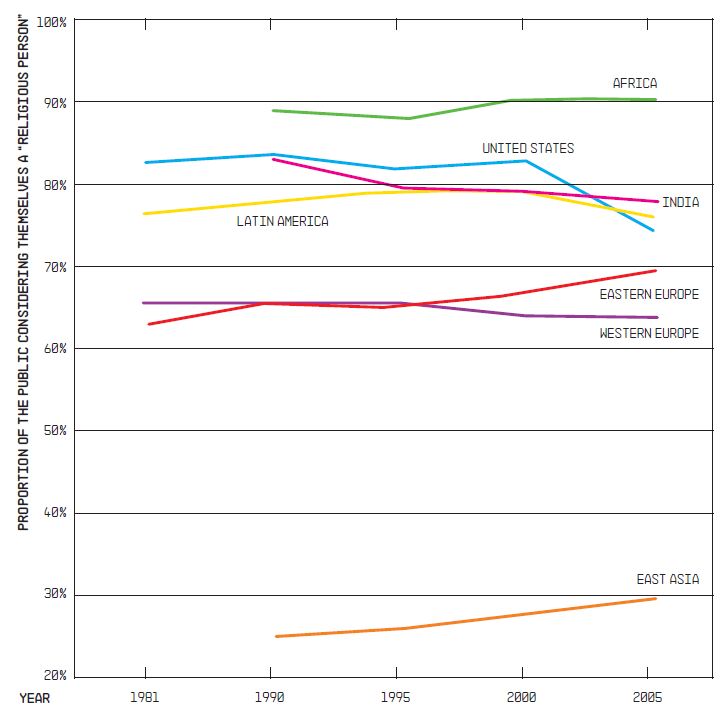

Does this wave of religious politics reflect a newfound religious commitment among the publics of non-Western societies? Since 1981, the Values Surveys have asked respondents whether they consider themselves to be “religious,” “non-religious,” or “a convinced atheist,” and these data allow us to examine trends in religiosity in the developing world. While there are many different measures of religiosity, including frequency of prayer, religious attendance, or one’s personal belief in God, if religion has become more salient in people’s political and social lives, self-identification as religious certainly ought to have risen. Figure 1.0 shows the proportion of respondents across seven regions of the world who describe themselves as religious, drawing upon data from 12 countries in Western Europe, four countries in East Asia, six countries in Eastern Europe, four countries in Latin America, and two countries in Africa, plus the United States and India, which are included here individually.

Figure 1: Proportion of the Public Considering Themselves a “Religious Person,” by Year.

– “East Asia” includes China, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam.

– “Western Europe” includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Great Britain, and West Germany.

– “Eastern Europe” includes Hungary, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, and East Germany.

– “Latin America” includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico.

– “Africa” includes Nigeria and South Africa.

While the proportion of the religious has gradually risen in East Asia and Eastern Europe, it has fallen or fluctuated randomly in India and Latin America. And while the proportion identifying as religious is very high across almost all regions of the world, a level of around two-thirds is consistent with the highly secular norms and legal institutions found in contemporary Europe.

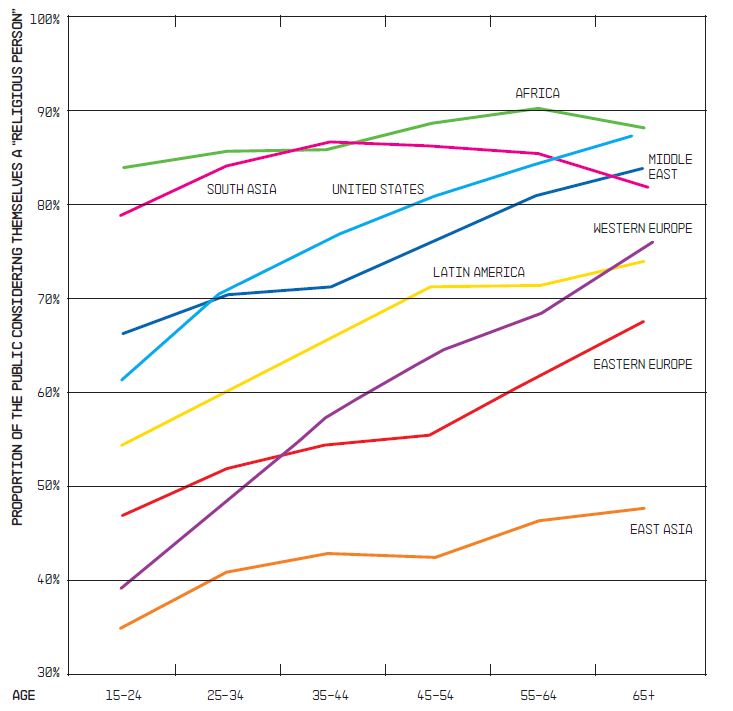

Unfortunately insufficient time-series data exists to be able to include the Middle East in Figure 1, which is the region that much of the “resurgence of religion” argument concerns. Nonetheless, it is possible to pool the data collected from the Middle East during the 1999–2001 and 2005–7 waves of the Values Surveys in order to gain a sense of the degree of intergenerational value-change occurring within the region, and thereby to make inferences regarding changes over time. Social scientists often look at intergenerational differences as evidence of long-term patterns of change, as through the socialization process, each birth cohort may adopt beliefs and values that persist through the life-cycle. For example, those growing up in the West during the 1960s may be likely to adopt from a young age more liberal attitudes regarding drug-use, sexual morality, and military involvement overseas than their parents, as a result of having taken part in the student movements that culminated in the 1968 protests (Inglehart 1971, 1977). While from a mere cross-section it is not possible to disentangle generational from life-cycle effects that alter attitudes as individuals move from youth to middle-age and then retirement, there is strong evidence that most values are learnt early in life, in the family, school and community, so that the enduring values of different birth cohorts can be attributed mainly to their formative experiences in childhood and adolescence. For the purposes of intergenerational comparison, therefore, we break down the cross-sectional data into 10-year birth cohorts.

When religious participation is analyzed by birth cohort and by region, the gradual disengagement of younger generations from religious identification is brought into focus. Interestingly, the results also suggest no rise in religious identity in the countries of the Middle East, where the young are steadily less likely to identify as religious than the elderly. In this regard, the intergenerational pattern appears remarkably similar to Europe or the United States, where a similar pattern of youthful non-observance can be seen. While this trend could be interpreted as a life-cycle effect, with individuals facing an inherent tendency to become more religious as they grow older, the pattern in Africa and India casts doubt on this association, as in these societies the young are barely less religious than the old. And in Western Europe and North America, we know from the time-series evidence that there is a gradual secularization process underway, and this is consistent with the generational trend seen here. Together, these facts hold out the possibility that there may be an incipient process of secularization occurring in the Middle East, rather than the religious resurgence that is typically described.

Figure 2: Proportion of the Public Considering Themselves a “Religious Person,” by Age Cohort.

– “East Asia” includes China, Japan, South Korea, and Vietnam.

– “Western Europe” includes Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Great Britain, and West Germany.

– “Eastern Europe” includes Hungary, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovenia, and East Germany.

– “Latin America” includes Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico.

– “Africa” includes Nigeria and South Africa.

If it is not a resurgence of religious identification that explains the rise of religious identity politics in India, Central Asia, and the Middle East, how do we account for the breakthrough of movements such as India’s Hindutva, Turkey’s Justice and Development Party, or the Iranian Committees of Islamic Revolution? We believe that an answer to this question must be found, not in mass beliefs and values, but rather in the weakening position of the secular political elites that led these countries to independence. WVS data shows that societies such as Turkey or India have always been fundamentally religious, and remain so. However, they were ruled in their early years by secular elites trained in the institutions of the former colonial powers, such as Jawaharlal Nehru of India or Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan, or emerging from the ranks of the officer corps, such as Kemal Atatürk in Turkey, who brought with them the secular principles learnt in the colleges of Oxbridge or the training barracks. As most of the population remained poor, agrarian, and politically passive, during the first years of independent rule secular elites were able to impose Western models of secular governance, such as the secular constitutions that were initially implemented across the region, with little social opposition (7).

In the late twentieth century, however, these societies underwent a fundamental shift in social structure as they urbanized, witnessed the spread of mass literacy and higher education, and saw a shift from agrarian to commercial and industrial employment. The formation of new urban commercial classes outside of the traditional support base for the secular elite—the Congress system “vote banks” of India, the military and bureaucracy in Turkey or Iran—thus opened up a field within which new parties and movements could mobilize support among groups frustrated by widespread corruption and their exclusion from government patronage networks. Supporters of Islamic revolution in Iran and the Turkish Refah (welfare) and AK parties came not from the peasantry but from the urban middle strata, including the student movement, the merchant class, and both trade union and industrialist groups. The same is true of the voters who helped the Indian BJP to electoral victory in 1996 and the Israeli Likud party to its electoral breakthrough in 1977. While Marxist, nationalist, and liberal movements all competed to unite opponents to the governing party or elite, in many of these countries—including Iran, Turkey, India, and Israel—the mobilizing ideology best able to form a coalition between the new urban middle class and the urban poor was that rooted in the religious beliefs and practices of the population, albeit infused with a twist of nationalism, in the cases of India and Israel.

Since the 1970s, therefore, the first generation of secular political elites that governed during the first decades of the post-war era in countries such as India, Pakistan, Israel, Turkey, and Iran have seen their position overturned by religious parties and movements. In India, the “Congress system” that united lower-caste groups and the urban sector began to fall apart in the 1960s as caste minorities broke away to form independent parties, and the private-sector urban middle class gradually swung behind the Hindu nationalist BJP party. In Pakistan, the secular Zulfikar Bhutto lost power to a coup d’état by the more conservative General Zia Ul-Haq, who proceeded to declare Islam as the country’s state religion, to the pleasure of the country’s clerical and feudal classes. In Israel, a secular consensus around the socialist policies of the Labor Party persisted from 1948 to 1977, but was shattered by the success of Likud in drawing middle-class Sephardic and “Russian” voters to a harder form of Zionist nationalism. In Turkey, conservative parties with a strong religious undercurrent repeatedly won democratic elections between 1950 and the present, only to be overturned by military coups; the Justice and Development Party has remained in power until now not due to the electorate but the emasculation of the military. Finally, in Iran, an absolutist monarchy supported by the Western powers rapidly collapsed once the iron fist of the Shah loosened its grip, giving way to a full-scale social revolution that swept away all vestiges of secular government.

Though these outcomes reflect a remarkable blossoming of religious politics, it is important to remember that secular norms and institutions never had widespread public support in these countries (Gellner 1993). The hegemony of secular elites and institutions was largely an after-effect of Western colonial influence, and as such were unlikely to last more than a single generation: insofar as we have survey data available, it shows that religious identities and values are widespread in developing countries, and have always been so. It is thus not surprising that as soon as mass, democratic politics had taken root it led immediately to what Huntington termed “indigenization”: a movement towards religious recidivism and cultural revivalism (Huntington 1996).

Thus, just as Western countries have typically moved towards secular policies and institutions through legislative votes and popular plebiscite, ironically in developing countries, desecularization has likewise occurred through the same means of democratic participation. Such is the “democracy paradox”: as non-Western societies adopt liberal-democratic institutions, it is followed by the rise of illiberal movements and the implementation of illiberal policies. In Afghanistan, the newly elected government of Hamid Karzai approved a constitution in 2004, which had been drafted in consultation with the country’s Loya Jirga, declaring Islam as the country’s state religion, instituting the Hanafi code of Shari’a law, and rewarding apostasy with capital punishment. In Iraq, a referendum in 2005 also replaced Hussein’s secular 1990 constitution with a document instituting Shari’a as the national law. In Sri Lanka, the introduction of democracy allowed Sinhalese nationalists to gain power in 1956, and Buddhism to be declared the country’s official religion in the 1972 constitution. In Bangladesh, it was a parliamentary vote in 1988 that made Islam the state religion, and though opposition parties opposed the decision at the time, they subsequently changed their position so as not to alienate conservative Muslim voters. In Turkey, the popularly elected AK party has begun implementing desecularization policies, including the lifting of the university headscarf ban in 2007 and a proposed introduction of prayer sections in public schools, following in the footsteps of the Democratic Party of the 1950s and the Welfare Party of the 1990s (whose attempts at those times were vetoed by the military). In Iran, the establishment of an Islamic Republic in 1979 was the result of a social revolution that saw massive popular participation, and though its subsequent democratic politics are constrained by the religious hierarchy, even reformist politicians today do not question the role of Shi’a Islam as the country’s official religion, the use of Shari’a law, or the need for moral censorship. In Western societies, liberty and democracy advance together. In the religiously conservative societies of the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa, this is not obviously so.

A good illustration of this point is to be found in data from the Values Surveys, which since 1981 have asked respondents whether they believe that though democracy “may have its problems” it is nonetheless “better than any other form of government.” In countries across the world, including the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia, large majorities agree with this point of view. 88% of respondents in the Middle East felt that democracy is the best means of exercising power, similar to the proportions in Western Europe (93%) and the United States (90%). Publics in non-Western societies, therefore, by and large agree with the view that elections, referenda, and representative government should form the basis of political life and government. However, very divergent views exist regarding the functioning and outcomes of democratic rule, and in particular regarding the role of religion in public life. The World Values Surveys also asked respondents how “essential” they thought a range of institutional norms were as characteristics of democracy, ranging from respect for civil liberties, to the ability to hold referenda, to more eclectic provisions, such as religious mediation or military monitoring of the government. Respondents were given a list of attributes, and asked to rate these on a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 indicating that it is “an essential characteristic of democracy” and 1 that it is “not essential.” In three of the five Islamic societies in which this question was asked, the majority of respondents leaned toward “having religious authorities interpret the laws” as “essential” for democracy, as indicated by a response in the range from 6 to 10 (8). By contrast, in Western Europe only 10.1% of respondents took this view, while in the United States, only 14% did so. Meanwhile, respondents were asked regarding the importance in a democracy of “women having the same rights as men,” a question that touches upon an important point given the historical denial of women’s suffrage in many countries, and continuing legal provisions that systematically treat men and women differently, such as when giving testimony in Shari’a courts. In Iraq, the one Arab democracy in the sample, respondents were divided between 57% who felt that equal rights were an element of democracy, and 43% who leaned against this view. In Western Europe, by contrast, 94.2% of respondents on average answered that equal rights were essential to their conception of democracy. Clearly, there are sharp divergences in how cultural traditions interpret the basic principles of representative government, and many non-Western societies in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia have a conception of civic representation that differs fundamentally from the Western model.

Conclusion

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the world appears to be dividing into two camps. On the one hand are the secular societies of Europe, North America, and developed East Asia, where the state is separated from religious life, social attitudes have become more accepting of women’s rights and alternative lifestyles, and legislative changes have relaxed restrictions against prostitution, abortion, and divorce. When migrants who do not share Western norms and values enter these societies, they are expected to accept rules regarding secular education, tolerance of sexual minorities, and women’s rights, or face legal barriers and punishments. On the other hand are the societies of the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia. In these countries secular constitutions have often been rewritten, public opinion remains firmly devout, and religious laws have increasingly come into force. While religious identification has not necessarily strengthened in such countries during recent decades, the mobilization of the masses into political life has brought religious movements to parliament and government, overturning the secular institutions that Western-educated and Western-backed leaders introduced during the early post-independence period.

In the coming decades, will this gap between sacred and secular worlds widen further, or will there by contrast be a new process of convergence? In answering this question, it is useful to distinguish between two different kinds of secularity, namely, secularization of the state and secularization of the individual. The first of these, state secularity, is the differentiation of secular spheres, such as the bureaucracy and the market, from religion. By this definition, Turkey or India may be considered secular (by virtue of their constitutional arrangements), though neither has a secular culture. The second form, individual secularity, is the decline of religious practices and beliefs, such as prayer, attending religious services, or following religious strictures. This is the form of secularization that prevails, to varying degrees and extents, in parts of Western Europe, Asia, and the Americas, though is comparatively rare elsewhere.

In the West secularization has spread to both domains. Starting the eighteenth century in France and the United States, and extending to the late twentieth century with the official disestablishment of the church in Italy, Spain, or Sweden, religion and politics were officially separated and public institutions made free of religious ritual or affiliation. Over the course of the twentieth century, religious attendance declined across most Western societies, and during the late twentieth century moral restrictions were liberalized in areas such as divorce, prostitution, abortion, and same-sex marriage. While there are some remaining areas where further liberalization is possible, for example, the use of recreational drugs, the key legislative changes were introduced in the 1970s and “moral issues” remain contentious only in outlier countries, such as Poland or the United States, where adherence to traditional religious edicts remains important among some groups in society.

On the other hand, in non-Western societies secularization has stumbled at the first step. Secular constitutions were introduced during independence, demarcating the political realm from the spiritual, but this separation has proven unsustainable in the absence of a significant non-religious population, and the acceptance of secular liberal norms among the general populace. In some states such as Turkey and India the secular constitution remains in force, though in most other Middle Eastern and South Asian countries this is no longer so. A number of countries in the region continue to be run by secular Arab nationalist regimes; however, religious parties and movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood may eventually overturn the status quo in countries ranging from Egypt, to Jordan, to Syria or Tunisia. Meanwhile, in Turkey, it is conceivable that the military establishment proves unable to stem the pressure for political reform, and the country adopts a constitutional settlement that, if not similar to Iran, may at least resemble the more moderate religious laws in Israel. If a demarcation between the religious, political, and private spheres is to develop in this region of the world, it is unlikely to follow the Western pattern of the secular state being succeeded by the secular society, but will instead have to begin from the secularization of society and only then proceed to broader institutional reform.

What prospect is there for such a transformation to occur? We have seen that religious identification appears to be lower among younger generations in the Middle East, though this finding remains inconclusive at present. Despite the rollback of secular institutions, it is possible that these societies may eventually undergo a process of intergenerational value-change, similar to that observed in Western countries since the 1960s, with younger generations eventually rejecting the conservative norms of the elders and embracing a new set of values based around individual rights and alternative lifestyles. In theory, the economic development of the Arab countries, led by the Gulf States, and the entrenchment of a democratic culture based around free expression and the exchange of ideas, ought to lead eventually to a transformation in social attitudes, as individuals de-emphasize traditional values in favor of values emphasizing personal development and self-realization. Yet the pace of social change is glacial, and any evidence that we have, such as the intergenerational value differences in the Middle East, remains inconclusive. Even assuming a process of cultural change is underway, these societies are beginning from starting points that are far removed from the social consensus that prevails in the Western world, and as a result conflicts over religious values are likely to remain an enduring feature of our world.

Bibliography

Berger, P. “The Desecularization of the World: A Global Overview,” in Berger (ed.), Desecularization of the World: Resurgent Religion and World Politics. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005.

Casanova, J. Public Religion in the Modern World. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1994.

Dale, W. “The West and Its Antagonists: Culture, Globalization, and the War on Terrorism.” Comparative Strategy, Vol. 23, No. 3 (2004): 303–12.

Gellner, E. “Marxism and Islam: Failure and Success,” in A. Tamini (ed.), Power Sharing Islam? London: Liberty for Muslim World Publications, 1993.

Gilbert, G. World Population. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2005.

Huntington, S. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. London: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Inglehart, R. “The silent revolution in Europe: Intergenerational change in Post-Industrial Societies.” American Political Science Review, Vol. 65 (1971): 991–1017.

—. The Silent Revolution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977.

—. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Kepel, G. The Revenge of God. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994.

Najjar, F. “The Arabs, Islam and Globalization”. Middle East Policy, Vol. 12, No. 3, 2005.

World Bank. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2006.

Notes

- The growth of international terrorism, Hindu nationalism, and the reluctance of the European Union to admit Turkey, a predominantly Muslim country, are commonly viewed in support of this viewpoint.

- In the Netherlands, a loophole allowed prostitution activity throughout the twentieth century, but the trade was only fully legalized and regulated in 2000.

- This occurred in Sweden in 1972, France in 1981, Italy in 1994, and Britain in 1998, when abolition of the death penalty was at the same time made a criterion for membership of the European Union, and thereby also enacted across all new accession states.

- To date, legislation permitting same-sex partnership has also been completed in six US states.

- An ironic application of these laws occurred in the 1980s, when Muslim groups had attempted to bring a case against Satanic Verses author Salman Rushdie: the case could not be pursued, as the laws only related to the Anglican Church and not to Islam.

- However there are several European exceptions where blasphemy laws remain in vigor, notably in Greece and in Ireland.

- Of the secular constitutions initially written for Pakistan, Bangladesh, Turkey and India, only India and Turkey retain their secularity clauses. Pakistan adopted Islam as its state religion in 1973 and Bangladesh in 1988. Israel is an interesting case, as the Proclamation of Independence declared a “Jewish State” in 1948, yet did not clarify whether this was a reference to ethnicity or religion. An Israeli constitution was intended but never written, in part because of controversy surrounding this issue. The (legislative) laws of the Israeli state are used to enforce generally minor religious restrictions, such as Saturday closing (Sabbath) and rules against sale of pork products, though decisions concerning the latter are devolved to the municipal level.

- The three Islamic societies were Iraq, Indonesia, and Malaysia, where the figures were 56%, 54.9%, and 57.2%, while the other two cases were Burkina Faso and Mali, where the figures were 24% and 47.9%, respectively.

Comments on this publication