Data are the lifeblood of decision-making and the raw material for accountability. Without high-quality data providing the right information on the right things at the right time, designing, monitoring, and evaluating effective policies become almost impossible. Today there are unprecedented possibilities for informing and transforming society and protecting the environment. I describe the social science and computer architecture that will allow this data to be safely used to help adaptation to the new world of data, a world that is more fair, efficient, and inclusive, and that provides greater opportunities than ever before.

Prologue: Birth of the Age of Data

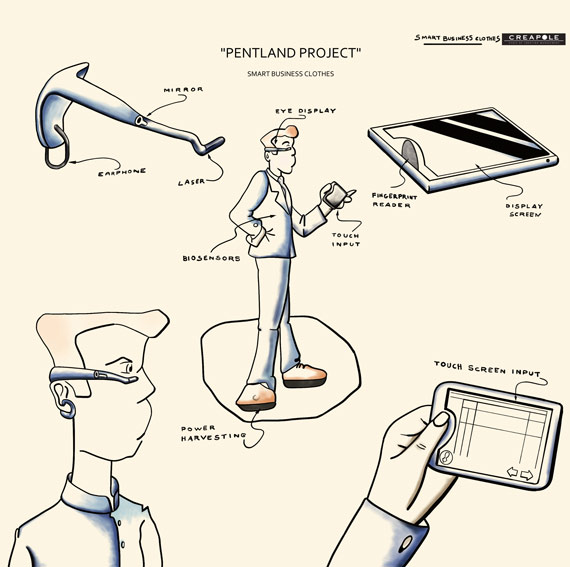

For me, the story starts more than twenty years ago when I was exploring wearable computing. My lab had the world’s first cyborg group: about twenty students who soldered together PCs and motorcycle batteries and little lasers so you could shoot images right into your eye. We tried to experiment with what the future would be. To put this in context, remember that there were very few cellphones in 1996. There was not even WiFi. Computers were big, hot things that sat on desks or in air-conditioned rooms. It was clear to me, however, that computers were going to be on our bodies and then basically everywhere.

We built this set of equipment for a whole group of people and then did lots of experiments with it. One of the first things everybody said about it was: “This is really cool, but I’ll never wear that.”

So, my next step was to get fashion schools involved in our work. The image on the facing page is from a French fashion school called Creapole. I had talked with students about where the technology was going and then they came up with designs. Intriguingly, they essentially invented things that looked like Google Glass and an iPhone down to the fingerprint reading.

It is interesting that by living with prototypes of the technology you can begin to see the future perhaps better than just by imagining it. The truly important thing that we learned by living this future was that vast amounts of data would be generated. When everybody has devices on them, when every interaction is measured by digital sensors, and when every device puts off data you can get a picture of society that was unimaginable a few years ago. This ability to see human behavior continuously and quantitatively has kicked off a new science (according to articles in Nature1 and Science2 and other leading journals) called computational social science, a science which is beginning to transform traditional social sciences. This is akin to when Dutch lens makers created the first practical lenses: microscopes and telescopes opened up broad new scientific vistas. Today, the new technology of living labs—observing human behavior by collecting a community’s digital breadcrumbs—is beginning to give researchers a more complete view of life in all its complexity. This, I believe, is the future of social science.

A New Understanding of Human Nature

Perhaps the biggest mistake made by Western society is our adherence to the idea of ourselves as “rational individuals.”

The foundations of modern Western society, and of rich societies everywhere, were laid in the 1700s in Scotland by Adam Smith, John Locke, and others. The understanding of ourselves that this early social science created is that humans are rational individuals, with “liberty and justice for all.”3 This is built in to every part of our society now—we use markets, we take direct democracy as our ideal of government, and our schools have dropped rhetoric classes to focus on training students to have better analytics skills.

But this rational individual model is wrong—and not just the rational part but, more importantly, the individual part. Our behavior is strongly influence by those around us and, as we will see, the source of most of our wisdom. Our ability to thrive is due to learning from other people’s experiences. We are not individuals but rather members of a social species. In fact, the idea of “rational individuals” reached its current form when mathematicians in the 1800s tried to make sense of Adam Smith’s observation that people “…are led by an invisible hand to … advance the interest of the society, and afford means to the multiplication of the species.”4 These mathematicians found that they could make the invisible hand work if they used a very simplified model of human nature: people act only to benefit themselves (they are “rational”), and they act alone, independent of others (they are “individuals”).

What the mathematics of most economics and of most governing systems assume is that people make up their minds independently and they do not influence each other. That is simply wrong. While it may not be a bad first approximation, it fails in the end because it is people influencing each other, peer-to-peer, that causes financial bubbles, and cultural change, and (as we will see) it is this peer-to-peer influence that is the source of innovation and growth.

Furthermore, the idea of “rational individuals” is not what Adam Smith said created the invisible hand. Instead, Adam Smith thought: “It is human nature to exchange not only goods but also ideas, assistance, and favors … it is these exchanges that guide men to create solutions for the good of the community.”5 Interestingly, Karl Marx said something similar, namely that society is the sum of all of our social relationships.

The norms of society, the solutions for society, come from peer-to-peer communication—not from markets, not from individuals. We should focus on interaction between individuals, not individual genius. Until recently, though, we did not have the mathematics to understand and model such networks of peer-to-peer interaction. Nor did we have the data to prove how it all really works. Now we have both the maths and the data.

What the mathematics of most economics and most governing systems assume is that people make up their minds independently. That is simply wrong, because it is people influencing each other that causes financial bubbles, and it is this peer-to-peer influence that is the source of innovation and growth

And so we come to the most fundamental question about ourselves: are we really rational individuals or are we more creatures of our social networks?

Wealth Comes from Finding New Opportunities

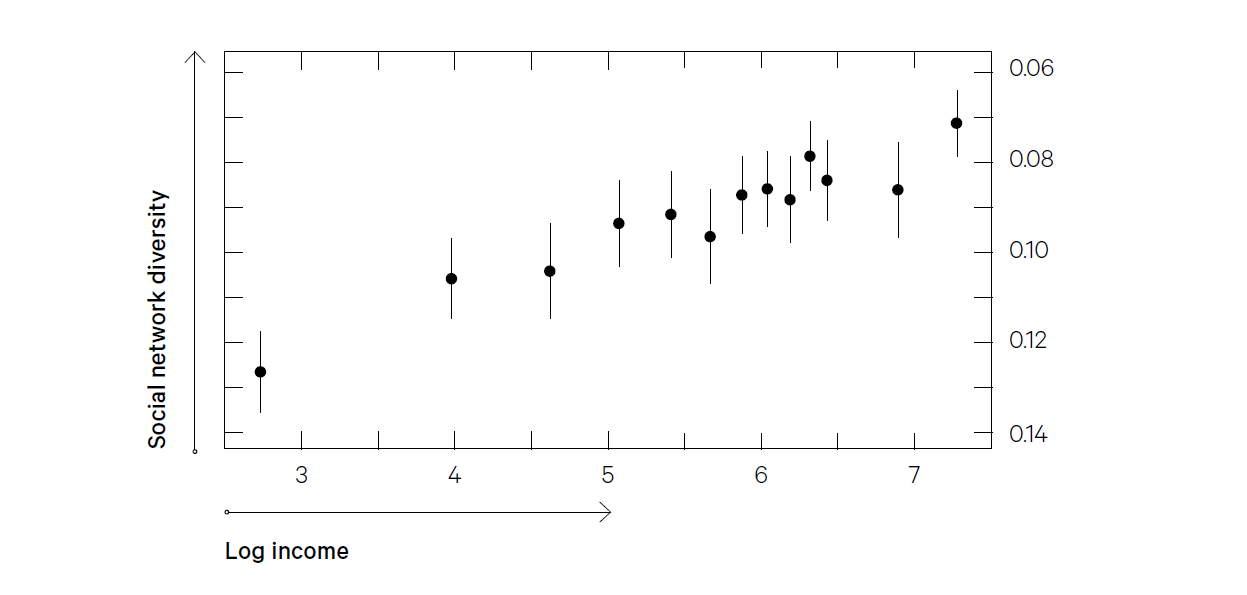

To answer the question of who we really are, we now have data available from huge numbers of people in most every society on earth and can approach the question using very powerful statistical techniques. For instance, let us look at a sample of 100,000 randomly selected people in a mid-income country and compare their ability to hear about new opportunities (measured by how closed or open their social networks are) to their income.

The answer is that people who have more open networks make more money. Moreover, this is not just an artifact of the way we measured their access to opportunities, because you can get the same result looking at the diversity of jobs of the people they interact with, or the diversity of locations of the people that they interact with. Shockingly, if you compare people who have a sixth-grade education to illiterate people, this curve moves only a little to the left. If you look at people with college educations, the curve moves only a little bit to the right. The variation that has to do with education is trivial when compared with the variation that has to do with diversity of interaction.

You may wonder if greater network diversity causes greater income or whether it is the other way around. The answer is yes: greater network diversity causes greater income on average (this is the idea of weak ties bringing new opportunities) but it is also true that greater income causes social networks to be more diverse. This is not the standard picture that we have in our heads when we design society and policy.

As people interact with more diverse communities, their income increases (100,000 randomly chosen people in mid-income country) (Jahani et al., 2017)

In Western society, we generally assume that individual features far outweigh social network factors. While this assumption is incorrect, nevertheless it influences our approach to many things. Consider how we design our schools and universities. My research group has worked with universities in several different countries and measured their patterns of social interactions. We find that social connections are dramatically better predictors of student outcome than personality, study patterns, previous training, or grades and other individual traits. Performance in school, in school tests, has more to do with the community of interactions that you have than with the things that the “rational individual” model leads us to assume are important. It is shocking.

It is better to conceive of humans as a species who are on a continual search for new opportunities, for new ideas, and their social networks serve as a major, and perhaps the greatest, resource for finding opportunities. The bottom line is that humans are like every other social species. Our lives consist of a balance between the habits that allow us to make a living by exploiting our environment and exploration to find new opportunities.

In the animal literature this is known as foraging behavior. For instance, if you watch rabbits, they will come out of their holes, they will go get some berries, they will come back every day at the same time, except some days they will scout around for other berry bushes. It is the tension between exploring, in case your berry bush goes away, and eating the berries while they are there.

This is exactly the character of normal human life. When we examined data for 100 million people in the US, we saw that people are immensely predictable. If I know what you do in the morning, I can know, with a ninety-percent-plus odds of being right, what you will be doing in the evening and with whom. But, every once in a while, people break loose and they explore people and places that they visit only very occasionally, and this behavior is extremely unpredictable.

Moreover, when you find individuals who do not show this pattern, they are almost always sick or stressed in some way. You can tell whether a person’s life is healthy in a general sense—both mental and physical—by whether they show this most basic biological rhythm or not. In fact, this tendency is regular enough that one of the largest health services in the US is using this to keep track of at-risk patients.

Humans, as a species, are on a continual search for new opportunities, for new ideas, and their social networks serve as a major, and perhaps the greatest, resource for finding opportunities

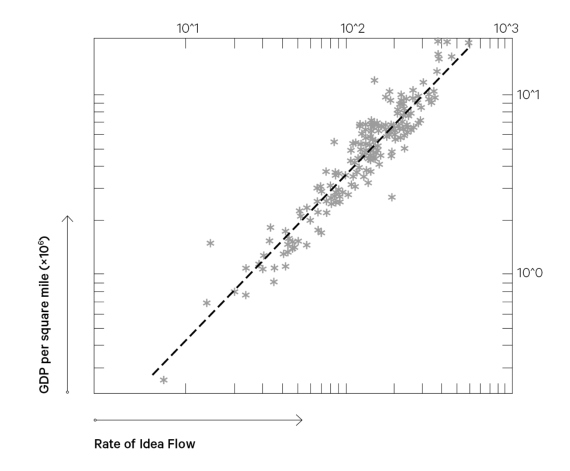

If you combine this idea of foraging for novelty with the idea that diverse networks bring greater opportunities and greater income, you would expect that cities that facilitate connecting with a wide range of people would be wealthier. So, we gathered data from 150 cities in the US and 150 cities in the EU and examined the patterns of physical interactions between people.

If your city facilitates more diverse interactions, then you likely have more diverse opportunities and over the long term you will make more money. From the figure above, you can see this model predicts GDP per square kilometer extremely accurately, in both the US and the EU. What that says is that the factors that we usually think about—investment, education, infrastructure, institutions—may be epiphenomenal. Instead of being the core of growth and innovation, they may make a difference primarily because they help or hinder the search for new opportunities. The main driver of progress in society may be the search for new opportunities and the search for new ideas—as opposed to skills in people’s heads or capital investment.

Summary: this new computational social science understanding of human behavior and society in terms of networks, the search for new opportunities, and the exchange of ideas might best be called Social Physics, a name coined two centuries ago by Auguste Comte, the creator of sociology. His concept was that certain ideas shaped the development of society in a regular manner. While his theories were in many ways too simplistic, the recent successes of computational social science show that he was going in the right direction. It is the flow of ideas and opportunities between people that drives society, providing quantitative results at scales ranging from small groups, to companies, cities, and even entire countries.

As face-to-face communication within a city allows interaction between more diverse communities, the city wealth increases. Data from 150 cities in the US and 150 in the EU (Pan et al., 2013)

* Data – – our model

Optimizing Opportunity

Once we understand ourselves better, we can build better societies. If the search for new opportunities and ideas is the core of human progress, then we should ask how best to accomplish this search. To optimize

opportunity, I will turn to the science of financial investment, which provides clear, simple and well-developed examples of the trade-off between exploiting known opportunities and exploring for new ones.

In particular I will look at Bayesian portfolio analysis. These methods are used to choose among alternative actions when the potential for profit is unknown or uncertain (Thompson, 1933). Many of the best hedge funds and the best consumer retail organizations use this type of method for their overall management structure.

The core idea associated with these analysis methods is that when decision-makers are faced with a wide range of alternative actions, each with unknown payoff, they have to select actions to discover those that lead to the best payoffs, and at the same time exploit the actions that are currently believed to be the best in order to remain competitive against opponents. This is the same idea as animals foraging for food, or people searching for new opportunities while still making a living.

To optimize opportunity, I will turn to the science of financial investment, which provides clear, simple and well-developed examples of the trade-off between exploiting known opportunities and exploring for new ones

In a social setting the payoff for each potential action can be easily and cheaply determined by observing the payoffs of other members of a decision-maker’s social network. This use of social learning dramatically improves both overall performance and reduces the cognitive load placed on the human participants. The ability to rapidly communicate and observe other decisions across the social network is one of the key aspects of optimal social learning and exploration for opportunity.

As an example, my research group recently examined how top performers maximize the sharing of strategic information within a social network stock-trading site where people can see the strategies that other people choose, discuss them, and copy them. The team analyzed some 5.8 million transactions and found that the groups of traders who fared the best all followed a version of this social learning strategy called “distributed Thompson sampling.” It was calculated that the forecasts from groups that followed the distributed Thompson sampling formula reliably beat the best individual forecasts by a margin of almost thirty percent. Furthermore, when the results of these groups were compared to results obtained using standard artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, the humans that followed the distributed Thompson sampling methodology reliably beat the standard AI techniques!

The use of social learning dramatically improves both overall performance and reduces the cognitive load placed on the human participants. The ability to rapidly communicate and observe other decisions across the social network is one of the key aspects of optimal social learning and exploration for opportunity

It is important to emphasize that this approach is qualitatively the same as that used by Amazon to configure its portfolio of products as well as its delivery services. A very similar approach is taken by the best financial hedge funds. Fully dynamic and interleaved planning, intelligence gathering, evaluation, and action selection produce a powerfully optimized organization.

This social learning approach has one more advantage that is absolutely unique and essential for social species: the actions of the individual human are both in their best interest and in the best interest of everyone in the social network. Furthermore, the alignment of individuals’ incentives and the organization’s incentives are visible and understandable. This means that it is easy, in terms of both incentives and cognitive load, for individuals to act in the best interests of the society: optimal personal and societal payoffs are the same, and individuals can learn optimal behavior just by observing others.

Social Bridges in Cities: Paths to Opportunity

Cities are a great example of how the process of foraging for new opportunities shapes human society. Cities are major production centers of society, and, as we have already seen, cities where it is easy to search for new opportunities are wealthier. Long-term economic growth is primarily driven by innovation in the society, and cities facilitate human interaction and idea exchange needed for good ideas and new opportunities.

These new opportunities and new ideas range from changes in means of production or product types to the most up-to-the-minute news. For example, success on Wall Street often involves knowing new events minutes before anyone else. In this environment, the informational advantages of extreme spatial proximity become very high. This may explain why Wall Street remains in a tiny physical area in the tip of Manhattan. The spatial concentration of economic actors increases productivity at the firm level by increasing the flow of new ideas, both within and across firms.

Our evidence suggests that bringing together people from diverse communities will be the best way to construct a vibrant, wealthy city. When we examine flows of people in real cities, however, we find that mixing is much more limited than we normally think. People who live in one neighborhood work mostly with people from only a couple of other neighborhoods and they shop in a similarly limited number of areas.

Physical interaction is mostly limited to a relatively small number of social bridges between neighborhoods. It is perhaps unsurprising that people who spend time together, whether at work or at play, learn from each other and adopt very similar behaviors. When I go to work, or to a store, I may see someone wearing a new style of shoe, and think “Hey, that looks really cool. Maybe I’ll get some shoes like that.” Or, perhaps I go to the restaurant that I always like, and somebody nearby orders something different, and I think “Oh, that looks pretty good. Maybe I’m going to try that next time.” When people spend time together they begin to mimic each other, they learn from each other, and they adopt similar behaviors and attitudes.

In fact, what you find is that all sorts of behaviors, such as what sort of clothes they buy, how they deal with credit cards, even diseases of behavior (like diabetes or alcoholism), flow mostly within groups connected by social bridges. They do not follow demographic boundaries nearly as much. In a recent study of a large European city, for instance, we found that social bridges were three hundred percent better at predicting people’s behaviors than demographics, including age, gender, income, and education

Groups of neighborhoods joined by rich social bridges form local cultures. Consequently, by knowing a few places that a person hangs out in, you can tell a huge amount about them. This is very important in both marketing and politics. The process of learning from each other by spending time together means that ideas and behaviors tend to spread mostly within the cluster, but not further. A new type of shoe, a new type of music, a political viewpoint, will spread within a cluster of neighborhoods joined by social bridges, but will tend not to go across cluster boundaries to other places. Advertisers and political hacks talk about influencers changing people’s minds. What I believe is that it is more about social bridges, people hanging out, seeing each other, interacting with each other, that determines the way ideas spread.

Long-term economic growth is primarily driven by innovation, and cities facilitate human interaction and idea exchange needed for good ideas and new opportunities

Summary: what Adam Smith said about people exchanging ideas—that it is the peer-to-peer exchanges that determine norms and behaviors—is exactly true. But what is truly stunning is that because we hold onto the “rational individual” model of human nature, we assume that preferences are best described by individual demographics—age, income, gender, race, education, and so forth—and that is wrong. The way to think about society is in terms of these behavior groups. Who do they associate with? What are those other people doing? The idea of social bridges is a far more powerful concept than demographics, because social bridges are the most powerful way that people influence each other. By understanding the social bridges in society, we can begin to build a smarter, more harmonious society.

Diversity and Productivity

While there has been a sharp increase in remote, digital communications in modern times, physical interactions between people remain the key medium of information exchange. These social interactions between people include social learning through observation (for example, what clothes to wear or what food to order) and through intermediary interactions (for example, word of mouth, mutual friends). To infer interactions between people, a network of interaction was first obtained based on the individual’s proximity. Physical proximity has been shown to increase the likelihood of face-to-face conversations, and this increase in interaction strength is widely used to help city planning and placement of city amenities.

The social bridges idea is that individuals can commonly be identified as part of a community based on where they live, work, and shop. Where you invest your most valuable resource—time—reveals your preferences. Each community typically has access to different pools of information, opportunities, or offers different perspectives. Diverse interactions should then increase a population’s access to the opportunities and ideas required for productive activity.

When we apply this logic to the cities in the US, Asia, and Europe, we find that the effect of this sort of interaction diversity has an effect comparable to that of increasing population. In other words, it is not just the number of individuals in the region that predicts economic growth, but also idea flow via the social bridges that connect them. If we compare the explanatory strength of interaction diversity with other variables such as average age or percentage of residents who received a tertiary education, we find that these traditional measures are much weaker at explaining economic growth than social bridge diversity. This means that models and civil systems that depend only on factors such as population and education may be missing the main effects.

A New Social Contract

In 2014 a group of big data scientists (including myself), representatives of big data companies, and the heads of National Statistical Offices from nations in both the north and south met within the United Nations headquarters and plotted a revolution. We proposed that all the nations of the world measure poverty, inequality, injustice, and sustainability in a scientific, transparent, accountable, and comparable manner. Surprisingly, this proposal was approved by the UN General Assembly in 2015, as part of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals.

This apparently innocuous agreement is known as the Data Revolution within the UN, because for the first time there is an international commitment to discover and tell the truth about the state of the human family as a whole. Since the beginning of time, most people have been isolated, invisible to government and without information about or input to government health, justice, education, or development policies. But in the last decade this has changed. As our UN Data Revolution report, titled “A World That Counts” put it:

Data are the lifeblood of decision-making and the raw material for accountability. Without high-quality data providing the right information on the right things at the right time, designing, monitoring and evaluating effective policies becomes almost impossible. New technologies are leading to an exponential increase in the volume and types of data available, creating unprecedented possibilities for informing and transforming society and protecting the environment. Governments, companies, researchers and citizen groups are in a ferment of experimentation, innovation and adaptation to the new world of data, a world in which data are bigger, faster and more detailed than ever before. This is the data revolution.6

More concretely, the vast majority of humanity now has a two-way digital connection that can send voice, text, and, most recently, images and digital sensor data because cellphone networks have spread nearly everywhere. Information is suddenly something that is potentially available to everyone. The Data Revolution combines this enormous new stream of data about human life and behavior with traditional data sources, enabling a new science of “social physics” that can let us detect and monitor changes in the human condition, and to provide precise, non-traditional interventions to aid human development.

Why would anyone believe that anything will actually come from a UN General Assembly promise that the National Statistical Offices of the member nations will measure human development openly, uniformly, and scientifically? It is not because anyone hopes that the UN will manage or fund the measurement process. Instead, we believe that uniform, scientific measurement of human development will happen because international development donors are finally demanding scientifically sound data to guide aid dollars and trade relationships.

Moreover, once reliable data about development starts becoming familiar to business people, we can expect that supply chains and private investment will start paying attention. A nation with poor measures of justice or inequality normally also has higher levels of corruption, and a nation with a poor record in poverty or sustainability normally also has a poor record of economic stability. As a consequence, nations with low measures of development are less attractive to business than nations with similar costs but better human development numbers.

Building a Data Revolution

How are we going to enable this data revolution and bring transparency and accountability to governments worldwide?

The key is safe, reliable, uniform data about the human condition. To this end, we have been able to carry out country-scale experiments that have demonstrated that this is a practical goal. For instance, the Data for Developments (D4D) experiments that I helped organize for Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal, each of which had the participation of hundreds of research groups from around the world, have shown that satellite data, cellphone data, financial transaction data, and human mobility data can be used to measure the sustainable development goals reliably and cheaply. These new data sources will not replace existing survey-based census data, but rather will allow this rather expensive data to be quickly extended in breadth, granularity, and frequency.7

But what about privacy? And won’t this place too much power in too few hands? To address these concerns, I proposed the “New Deal on Data” in 2007, putting citizens in control of data that are about them and also creating a data commons to improve both government and private industry (see http://hd.media.mit.edu/wef_globalit.pdf). This led to my co-leading a Word Economic Forum discussion group that was able to productively explore the risks, rewards, and cures for these big data problems. The research and experiments I led in support of this discussion shaped both the US Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights, the EU Data Protection laws, and is now helping China determine its data protection policies. While privacy and concentration of power will always be a concern, as we will shortly see there are good solutions available through a combination of technology standards (for example, “Open Algorithm” described below) and policy (e.g., open data including aggregated, low-granularity data from corporations).

D4D experiments have shown that satellite data, cellphone data, financial transaction data, and human mobility data can be used to measure sustainable development goals reliably and cheaply

Following up on the promise uncovered by these academic experiments and World Economic Forum discussions, we are now carrying out country-scale pilots using our Open Algorithms (OPAL) data architecture in Senegal and Colombia with the help of Orange S.A., the World Bank, Paris21, the World Economic Forum, the Agence Française de Développement, and others. The Open Algorithms (OPAL) project, developed originally as an open source project by my research group at MIT (see http://trust.mit.edu), is now being deployed as a multi-partner socio-technological platform led by Data-Pop Alliance, Imperial College London, the MIT Media Lab, Orange S.A., and the World Economic Forum, that aims to open and leverage private sector data for public good purposes (see http://opalproject.org). The project came out of the recognition that accessing data held by private companies(for example, call detail records collected by telecom operators, credit card transaction data collected by banks, and so on) for research and policy purposes requires an approach that goes beyond ad hoc data challenges or through nondisclosure agreements. These types of engagements have offered ample evidence of the promise, but they do not scale nor address some of the critical challenges, such as privacy, accountability, and so on.

OPAL brings stakeholders together to determine what data—both private and public—should be made accessible and used for which purpose and by whom. Hence, OPAL adds a new dimension and instrument to the notion of “social contract,” namely the view that moral and/or political obligations of people are dependent upon an agreement among them to form the society in which they live. Indeed, it provides a forum and mechanism for deciding what levels of transparency and accountability are best for society as a whole. It also provides a natural mechanism for developing evidence-based policies and a continuous monitoring of the various dimensions of societal well-being, thus offering the possibility of building a much deeper and more effective science of public policy.

OPAL is currently being deployed through pilot projects in Senegal and Colombia, where it has been endorsed by and benefits from the support of their National Statistical Offices and major local telecom operators. Local engagement and empowerment will be central to the development of OPAL: needs, feedback, and priorities have been collected and identified through local workshops and discussions, and their results will feed into the design of future algorithms. These algorithms will be fully open, therefore subject to public scrutiny and redress. A local advisory board is being set up to provide guidance and oversight to the project. In addition, trainings and dialogs will be organized around the project to foster its use and diffusion as well as local capacities and awareness more broadly. Initiatives such as OPAL have the potential to enable more human-centric accountable and transparent data-driven decision-making and governance.

In my view, OPAL is a key contribution to the UN Data Revolution—it is developing and testing a practical system that insures that every person counts, their voices are heard, their needs are met, their potentials are realized, and their rights are respected.

Smarter Civic Systems

Using the sort of data generated by OPAL, computational social science (CSS) researchers have shown that Jane Jacobs, the famous urban visionary and advocate of the 1900s, was right: cities are engines of innovation, powered by the interaction of diverse communities. The question, then, is how to best harness this innovation. Today we use markets and market forces to separate good ideas from bad, and to grow the good ones to scale.

But, as CSS has shown, markets are a bad way to characterize human society. They are based on greedy optimization and ignore the power of human social processes. The only reason that they work at all may be that regulators “tweak” them to suit the regulators’ preconceived notions of good and bad. Direct democracy suffers from the same problems, which is why most countries have representative democracy instead. Unfortunately, representatives in such systems are all too prone to capture by special interests.

Another path to harnessing human innovations is suggested by the insight that powers today’s cutting-edge artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms. Most of today’s AI starts with a large, random network of simple logic machines. The random network then learns by changing the connections between simple logic machines (“neurons”), with each training example slightly changing the connections between all the neurons based on how the connection contributes to the overall outcome. The “secret sauce” is the learning rule, called the credit assignment function, which determines how much each connection contributed to the overall answer. Once the contributions of each connection have been determined, then the learning algorithm that builds the AI is simple: connections which have contributed positively are strengthened; those that have contributed negatively are weakened.

This same insight can be used to create a better human society, and, in fact, such techniques are already widely used in industry and sports, as I will explain. To understand this idea, imagine a human organization as a kind of brain, with humans as the individual neurons. Static firms, symbolized by the ubiquitous organization chart, have fixed connections and, as a result, a limited ability to learn and adapt. Typically, their departments become siloed, with little communication between them so that the flow of fresh, crosscutting ideas is blocked. As a consequence, these statically configured, minimally interconnected organizations risk falling to newer, less ossified competitors.

But if an organization’s skills can be supercharged by adopting the right sort of credit assignment function, then the connections, among individuals, teams, and teams of teams, might continuously reorganize themselves in response to shifting circumstances and challenges. Instead of people being forced to be simple rule-following machines, people would engage in continuous improvement that is seen in the Kaizen-style manufacturing developed by Toyota, the “quality team” feedback approach adopted by many corporations, or the continuous, data-driven changes in sports team rosters described in the book Moneyball.

Another path to harnessing human innovations is suggested by the insight that powers today’s cutting-edge AI algorithms. The “secret sauce” is the learning rule, called the credit assignment function, which determines how much each connection contributed to the overall answer

The key to such dynamic organizations is continuous, granular, and trustworthy data. You need to know what is actually happening right now in order to continuously adapt. Having quarterly reports, or conducting a national census every ten years, means that you cannot have an agile learning organization or a learning society. OPAL and the data revolution provide the foundation upon which a responsive, fair, and inclusive society can be built. Without such data we are condemned to a static and paralyzed society that will necessarily fail the challenges we face.

Today, online companies such as Amazon and Google, and financial services firms such as Blackrock and Renaissance, have enthusiastically adopted and developed these data-driven agile approaches to manage their organizations. Obviously, such continuously adapting and learning organizations, even if assisted by sophisticated algorithms, will require changing policy, training, doctrine, and a wide spectrum of other issues.

Avoiding Chaos

To most of us change means chaos. So how can we expect to achieve this vision of a dynamic society without continuous chaos? The key is to have a credit assignment function that both makes sense for each individual and yet at the same time yields global optimal performance. This would be a real version of the “invisible hand,” one that works for real people and not just for rational individuals.

The phrase makes sense means that each individual must be able to easily understand their options and how to make choices that are good for them as an individual, and also understand how it is that what is good for them is also good for the whole organization. They must be able to easily and clearly communicate the choices they have made and the anticipated or actual outcomes resulting from those choices. Only through this sort of understanding and alignment of incentives within society will the human participants come to both trust and helpfully respond to change.

Sound impossible? It turns out that people already quite naturally do this in day-to-day life. As described in the first section of this paper, people rely on social learning to make decisions. By correctly combining the experiences of others we can both adapt to rapidly changing circumstances and make dramatically better day-to-day decisions. Earlier I described how people naturally did this in a social financial platform.

The keys to successful rapid change are granular data about what other people are doing and how it is working out for them, and the realization that we cannot actually act independently because every action we take affects others and feeds back to ourselves as others adapt to our actions. The enemies of success are activities that distort our perception of how other people live their lives and how their behaviors contribute to or hinder their success, for example, advertising, biased political advocacy, segregation, and the lack of strong reputational mechanisms all interfere with rapid and accurate social learning.

The Human Experience

How can we begin to encourage such learning organization and societies? The first steps should be focused on accurate, real-time knowledge about the successes and failures that others have experienced from implementing their chosen strategies and tactics. In prehistoric times people knew quite accurately what other members of their village did and how well it worked, and this allowed them to quickly develop compatible norms of behavior. Today we need digital mechanisms to help us know about what works and what does not work. This sort of reputation mechanism is exactly the benefit of using an architecture like OPAL.

Strong reputation mechanisms allow local community determination or norms and regulations instead of laws created and enforced by elites. For instance, frontline workers often have better ideas about how to deal with challenging situations than managers, and tactical engineers know more about how a new capability is shaping up than its designers do. The secret to creating an agile, robust culture is closing the communications gap between people who do and people who organize, so that employees are both helping to create plans and executing them. This closure fits with another key finding: developing the best strategy in any scenario involves striking a balance between engaging with familiar practices and exploring fresh ideas.

Actively encouraging sharing in order to build community knowledge offers another benefit: when people participate and share ideas, they feel more positive about belonging to the community and develop greater trust in others. These feelings are essential for building social resilience. Social psychology has documented the incredible power of group identities to bond people and shape their behavior; group membership provides the social capital needed to see team members through inevitable conflicts and difficult periods.

Summary: A New Enlightenment

Many of the traditional ideas we have about ourselves and how society works are wrong. It is not simply the brightest who have the best ideas; it is those who are best at harvesting ideas from others. It is not only the most determined who drive change; it is those who most fully engage with like-minded people. And it is not wealth or prestige that best motivates people; it is respect and help from peers.

The disconnect between traditional ideas about our society and the current reality has grown into a yawning chasm because of the effects of digital social networks and similar technology. To understand our new, hyper-connected world we must extend familiar economic and political ideas to include the effects of these millions of digital citizens learning from each other and influencing each other’s opinions. We can no longer think of ourselves as only rational individuals reaching carefully considered decisions; we must include the dynamic social networking effects that influence our individual decisions and drive economic bubbles, political revolutions, and the Internet economy. Key to this are strong and rapid reputation mechanisms, and inclusiveness in both planning and execution.

Today it is hard to even imagine a world where we have reliable, up-to-the-minute data about how government policies are working and about problems as they begin to develop. Perhaps the most promising uses for big data are in systems like OPAL, which allow statisticians in government statistics departments around the world to make a more accurate, “real-time” census and more timely and accurate social surveys. Better public data can allow both the government and private sectors to function better, and with these sorts of improvements in transparency and accountability we can hope to build a world in which our government and social institutions work correctly.

Historically we have always been blind to the living conditions of the rest of humanity; violence or disease could spread to pandemic proportions before the news would make it to the ears of central authorities. We are now beginning to be able to see the condition of all of humanity with unprecedented clarity. Never again should it be possible to say: “We didn’t know.”

Comments on this publication