Over the last decade, the analysis of ancient DNA has emerged as cutting-edge research that uses methods (genetics) and concepts (hybridization) not previously common in the field of anthropology. Today, we are the only human species on the planet, but we now know that we had offspring with others that no longer exist and have inherited some of their genes. What does it mean to be a hybrid? What are the implications of having the genetic material of other hominins in our blood? Was this hybridization a factor in the Neanderthals’ extinction? Does it shift our perspective on human diversity today? Both genetic and fossil evidence gathered over the last decade offer a more diverse and dynamic image of our origins. Many of the keys to Homo sapiens’ success at adapting may possibly lie in this miscegenation that not only does not harm our identity, but probably constitutes a part of our species’ hallmark and idiosyncrasies.

In normal use, the word “investigation” is filled with connotations of progress and future. Paradoxically, its etymology lies in the Latin word investigare, which comes, in turn, from vestigium (vestige or footprint). Thus, the original meaning of “investigate” would be “to track.” For those of us who study ancient eras, returning to the root of the word “investigate” brings out the frequently overlooked idea that progress is only possible through knowing and learning from the past. Paleoanthropology is the field that studies the origin and evolution of man and tries to reconstruct the history of biological and cultural changes experienced by our ancestors since the lines that have led to humans and chimpanzees split some six million years ago. One of the main bodies of evidence on which the study of human evolution draws is fossils of extinct hominid species. This frequently leads to the erroneous idea that paleoanthropology is an area of study cloistered in the past, and that its contribution to our understanding of today’s human beings consists, at most, of a few anecdotes. In fact, research into human evolution over the last decade has invalidated that paradigm in both the methodological and conceptual sense with research on the very horizon of knowledge that has contributed previously unknown knowledge about our own species.

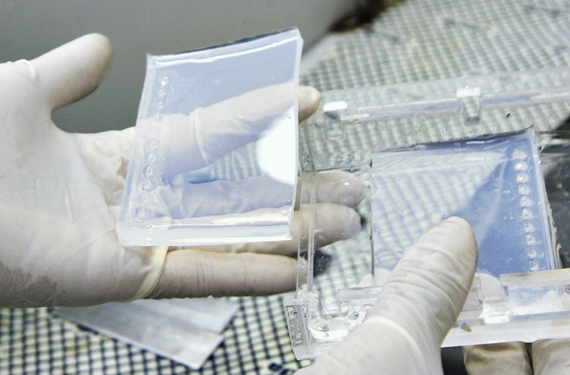

The past is now uncovered using technology of the future. The need “to make the dead talk” and to maximize the information that can be extracted from cherished and rare fossil and archeological finds has led paleontologists and archeologists to perfect and fully exploit current methods—sometimes to define new lines of investigation. The application, for example, of high-resolution imaging techniques to the study of fossils has spawned an independent methodological branch known as virtual anthropology. Thus, the digital age has also reached the world of the past, and, with these techniques, it is now possible to study a fossil in a nondestructive manner by making two- and three-dimensional measurements and reconstructions of any of its surfaces, whether internal or external. The best example of this fruitful relation between technology and the study of the past, however, appears in the consolidation of a recent research area: paleogenetics, that is, the analysis of ancient DNA. The awarding of the Princess of Asturias Prize for Scientific and Technical Research to Swedish biologist Svante Pääbo, considered one of the founders of paleogenetics, illustrates the importance that molecular studies have attained in the reconstruction of a fundamental part of our history. The team led by Pääbo, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig (Germany), has pioneered the application of high-performance DNA sequencing techniques to the study of ancient DNA, thus making it possible to analyze the complete genomes of extinct organisms. Their collaboration with scientists researching the Sierra de Atapuerca archeological sites in the province of Burgos has, in fact, led to a scientific landmark: extracting DNA from the hominins at the Sima de los Huesos site (430,000 years old). This is the oldest DNA yet recovered in settings without permafrost.

The consolidation of paleogenetic studies has provided data on the origin of our species—Homo sapiens—and the nature of our interaction with other now-extinct species of hominins. Such knowledge was unimaginable just ten years ago. Until now, the story of Homo sapiens’ origin was practically a linear narrative of its emergence at a single location in Africa. Privileged with a variety of advanced physical and intellectual capacities, modern humans would have spread to all of the continents no more than 50,000 years ago. That is the essence of the “Out of Africa” theory, which suggests that in its expansion across the planet Homo sapiens would have replaced all archaic human groups without any crossbreeding at all. Molecular analyses have now dismantled that paradigm, revealing that modern humans not only interbred and produced fertile offspring with now-extinct human species such as Neanderthals, but also that the genetic makeup of today’s non-African human population contains between two and four percent of their genes. Moreover, through genetic analysis of hand bones discovered in a cave in Denisova, in the Altai mountains of Siberia, geneticists have identified a new human population. We have practically no fossil evidence of them, and therefore know very little about their physical appearance, but we do know that they were different from both Neanderthals and modern humans. Colloquially known as Denisovans, they must have coexisted and crossbred with our species and with Homo Neanderthalensis, as between four and six percent of the genetic makeup of humans currently living in Papua and New Guinea, Australia and Melanesia is of Denisovan origin.

The past is now uncovered using technology of the future. The need to maximize the information that can be extracted from fossil and archeological remains has led to the perfection and exploitation of current methods and the development of new lines of research

Paleogenetics constitutes frontier research in many of the senses described by science historian Thomas S. Kuhn in his work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), as it has made it possible to use methods (genetics) and concepts (hybridization) that were not previously common in paleoanthropology, thus providing unexpected results that bring the ruling paradigm into question. Moreover, it has opened a door to unforeseen dimensions of knowledge. Although today we are the only human species on Earth, we now know that we were not always alone, and that we knew and had offspring with other humans that no longer exist but have left their genetic mark on us. This triggers a degree of intellectual vertigo. What does it mean to be a hybrid? What was it like to know and coexist with a different intelligent human species? What are the implications of having genetic matter from other human species running through our veins? Was this hybridization involved in the extinction of our brothers, the Neanderthals? Does this shed new light on the diversity of humans today?

It is difficult to resist the fascination of exploring the most ancient periods, despite the relative scarcity of available evidence, but over the last decade paleoanthropology has proved a wellspring of information on more recent times, especially with regard to our own species. Genetic data, along with new fossil discoveries and new datings that place our species outside the African continent earlier than estimated by the “Out of Africa” theory, have uncovered a completely unknown past for today’s humans.

In this context, the present article will review some of the main landmarks of human evolution discovered in the last decade, with a particular emphasis on philosopher Martin Heidegger’s affirmation that “the question is the supreme form of knowledge” and the idea that a diagnosis of any science’s health depends not so much on its capacity to provide answers as to generate new questions—in this case, about ourselves.

Our Hybrid Origin

One of the main problems with the idea of hybrid species is that it contradicts the biological concept of species originally formulated by evolution biologist Ernst Mayr. According to Mayr, a species is a group or natural population of individuals that can breed among themselves but are reproductively isolated from other similar groups. This concept implies that individuals from different species should not be able to crossbreed or have fertile offspring with individuals who do not belong to the same taxon. And yet, nature offers us a broad variety of hybrids—mainly in the plant world, where species of mixed ancestry can have offspring that are not necessarily sterile. This is less common among animals or at least less known, although there are known cases among species of dogs, cats, mice, and primates, including howler monkeys. One particular example among primates is the hybrids that result from crossbreeding different species of monkeys from the genus Cercopithedidae, familiarly known as baboons. As we shall see, they have provided us with very useful information. An additional problem is that, until molecular techniques were applied to paleontological studies, the concept of biological species was difficult to establish in fossils. We would have needed a time machine to discover whether individuals from different extinct species could (and did) interact sexually, and whether those interactions produced fertile offspring. Moreover, there is very little information about the physical appearance of the hybrids, which further complicates attempts to recognize them in fossil evidence.

In the context of paleontology, the concept of species is employed in a much more pragmatic way, as a useful category for grouping individuals whose anatomical characteristics (and ideally, their behavior and ecological niche) place them in a homogenous group that can, in principle, be recognized and distinguished from other groups. This clear morphological distinction among the individuals we potentially assign to a species is used as an indirect indicator of their isolation from other populations (species) that would not have maintained their characteristic morphology if they had regularly interbred. Does the fact that H. sapiens and H. Neanderthalensis interbred signify that they are not different species? Not necessarily, although the debate is open.

Today we are the only human species on the planet, but we now know that we had offspring with others that no longer exist and that we have inherited some of their genes

The Neanderthals are hominins that lived in Europe some 500,000 years ago. Their extinction some 40,000 years ago roughly coincides with the arrival of modern humans in Europe, and this has led to the idea that our species may have played some role in their disappearance. Few species of the genus Homo have created such excitement as the Neanderthals, due to their proximity to our species and their fateful demise. The study of skeletal and archeological remains attributed to them offers an image of a human whose brain was of equal or even slightly larger size than ours, with proven intellectual and physical capacities. They were skilled hunters, but also expert in the use of plants, not only as food but also for medicinal purposes. Moreover, the Neanderthals buried their dead and used ornaments, and while their symbolic and artistic expression seems less explosive than that of modern humans, it does not differ substantially from that of the H. sapiens of their time. Indeed, the sempiternal debate as to the possible cultural “superiority” of H. sapiens to H. Neanderthalensis often includes an erroneous comparison of the latter’s artistic production to that of modern-day humans, rather than to their contemporaneous work. The recent datings of paintings in various Spanish caves in Cantabria, Extremadura, and Andalusia indicate they are earlier than the arrival of modern humans in Europe, which suggests that the Neanderthals may have been responsible for this type of art. If they were thus sophisticated and similar to us in their complex behavior, and able to interbreed with us, can we really consider them a different species? This debate is further heightened by genetic studies published in late 2018 by Viviane Slon and her colleagues, which suggest that Neanderthals, modern humans, and Denisovans interbred quite frequently. This brings into question the premise that some sort of barrier (biological, cultural, or geographic) existed that hindered reproductive activity among two supposedly different species.

Fossil and genetic data now available are still insufficient to support any firm conclusions, but it is important to point out that even when we are speaking of relatively frequent crossbreeding among individuals from different species (and living species have already supplied us with examples of this) we are not necessarily saying that such crosses are the norm in such a group’s biological and demographic history. There are circumstances that favor such crossbreeding, including periods in which a given population suffers some sort of demographic weakness, or some part of that population, perhaps a marginal part, encounters difficulty in procreating within its own group; or mainly in periods of ecological transition from one ecosystem to another where two species with different adaptations coexist. Ernst Mayr himself clarified that the isolation mechanisms that separate one lineage from another in reproductive terms consist of biological properties of individuals that prevent habitual crossbreeding by those groups, and while occasional crossbreeding might occur, the character of that exchange is not significant enough to support the idea that the two species have completely merged. And that is the key element here. The Neanderthals are probably one of the human species most clearly characterized and known through fossil evidence. Their low and elongated crania, with an obvious protuberance at the back (“occipital bun”), the characteristic projection of their faces around the nasal region (technically known as mid-facial prognathism) and the marked bone ridge at the brow (supraorbital ridge) are Neanderthal characteristics that remained virtually intact from their origin almost half a million years ago in Europe through to their extinction. If there really had been systematic and habitual interbreeding among Neanderthals and modern humans, it would probably have attenuated or modified those patterns. But in fact, the most pronounced examples of those morphological traits appear in the late Neanderthals. Moreover, except for genetic analyses, we have found no evidence that the two groups lived together. The digs at Mount Carmel, Israel, are the clearest example of physical proximity among the two species, but, in all cases, evidence of one or the other group appears on staggered layers—never on the same one. Thus, Neanderthals and humans may have lived alongside each other, but not “together,” and while there may have been occasional crossbreeding, this was not the norm. Therefore, modern humans cannot be considered a fusion of the two. In this sense, the hypothesis that Neanderthals disappeared because they were absorbed by modern humans loses strength.

A final interesting take on inter-species hybrids emerges from baboon studies by researchers such as Rebecca Ackermann and her team. It is popularly thought that a hybrid will present a morphology halfway between the two parent species, or perhaps a mosaic of features from both. But Ackermann and her colleagues have shown that hybrids frequently resemble neither of the parents, so that many of their characteristics are actually “morphological novelties.” Hybrids tend to be either clearly smaller or larger than their parents, with a high number of pathologies and anomalies that rarely appear in either of the original populations. Some of these anomalies, such as changes in the craniofacial suture, bilateral dental pathologies, and cranial asymmetries, undoubtedly reflect developmental “mismatches.” Thus, even when hybridization is possible, the “fit” can be far from perfect. And, in fact, paleogenomic studies, such as those by Fernando Méndez and his team, address the possibility that modern humans may have developed some kind of immune response to the Neanderthal “Y” chromosome, which would have repeatedly caused Homo sapiens mothers impregnated by Neanderthal fathers to miscarry male fetuses. This would, in turn, have threatened the conservation of Neanderthal genetic material.

Paleogenomic studies suggest that modern humans may have developed some kind of immune response to the Neanderthal “Y” chromosome, which would have repeatedly caused Homo sapiens mothers impregnated by Neanderthals to miscarry male fetuses

Along that line, we could consider that while hybridization may not have caused Neanderthals to disappear, it may have been a contributing factor. Far from the classic example of dinosaurs and meteors, extinction in the animal world is generally a slow process in which a delicate alteration of the demographic equilibrium does not require major events or catastrophes to tip the scales one way or the other. While the Neanderthals’ fertility may have been weakened by the mix, some experts suggest that by interbreeding with Neanderthals and Denisovans our species may have acquired genetic sequences that helped us adapt to new environments after we left Africa, especially through changes in our immune system. Thus, hybridization would have been advantageous for our species as a source of genes beneficial to our conquest of the world.

Further research is necessary to explore the effect of genetic exchange on the destiny of each of these species. But, while hybridization may have negatively affected Denisovans and/or Neanderthals, as they are the ones that disappeared, paleogenetics suggest that the interaction of modern humans with those extinct species was not necessarily violent. One of the most classic theories proposed to explain the Neanderthals’ disappearance is confrontation, possibly even violent conflict, between the two species. Homo sapiens has been described as a highly “invasive” species, and its appearance, like Attila’s horse, has been associated with the extinction of many species of large animals (“megafaunal extinction”), including the Neanderthals. While sex does not necessarily imply love, the fact that there is a certain amount of Neanderthal DNA running through our veins suggests that someone had to care for and assure the survival of hybrid children, and that reality may allow us to soften the stereotype of violent and overpowering Homo sapiens.

The “Hard” Evidence of Our Origin

There is no doubt that technological advances in recent years have led us to examine the small and the molecular. The methodological revolution of genetic analysis is bolstered by the birth of paleoproteomics (the study of ancient proteins), a discipline whose importance can only grow in the coming years. Nonetheless, the hard core and heart of anthropology has been and will continue to be fossils. Without fossils, there would be no DNA and no proteins; we would lack the most lasting and complete source of data on which paleoanthropology draws. While futuristic analysis techniques continue to emerge, reality reminds us that to move forward in this field we must literally and figuratively “keep our feet on the ground.” The ground is where we must dig, and that is where, with hard work and no little luck, we find the bones of our forebears. There is still much ground to be covered, and our maps are filled with huge fossil gaps. Regions such as the Indian Subcontinent or the Arabian Peninsula have barely been explored in that sense, so discoveries there are like new pieces that oblige us to reassemble the puzzle. Over the last decade, new and old fossils found in Asia are shifting the epicenter of attention toward the Asian continent and there are, foreseeably, many surprises in store. Even with regard to the reconstruction of our own species’ history, which has long been told exclusively in terms of Africa, the fossils discovered over the last decade have something to say.

From the standpoint of fossils, the hypothesis of our species’ African origin has rested mainly on the discovery there of the oldest remains attributable to Homo sapiens. These include the Herto and Omo skulls from Ethiopia, which are between 160,000 and 180,000 years old. The Qafzeh and Skhul sites in the Near East have provided an important collection of fossils also attributed to our species, which are between 90,000 and 120,000 years old. And yet, the “Out of Africa” hypothesis holds that our species was not able to enter Europe and Asia until some 50,000 years ago, so the presence of Homo sapiens in Israel was not considered dispersion or “exodus” as such.

Over the last decade, however, a significant number of fossils brings the 50,000-year date into question. These include the teeth and jaw found in Daoxian (Fuyan Cave) and Zhirendong, in South China, and the finger bone discovered in Al-Wusta (Saudi Arabia), which place our species outside Africa at least 80,000 years ago, although their presence may even be earlier than 100,000 years ago. With the discovery at a dig in Misliya (Israel) of a human jawbone dating from around 190,000 years ago—this is as old as the oldest African fossils attributable to Homo sapiens—it is becoming increasingly clear that our species was able to adapt to other territories earlier than we thought, although the debate is still open. Arguably, genetic evidence continues to suggest that modern humanity comes mainly from a process of dispersion that took place around 50,000 years ago. That does not, however, rule out earlier forays that may not have left any mark on modern humans—or perhaps we have simply not detected them yet. When we limit ourselves to maps with arrows representing the spread of humans, we may easily forget that hominins do not migrate in linear, directional ways, as if they were on an excursion or march with a predetermined destination or purpose. Like any other animal’s, human migration should be understood as the expansion or broadening of an area of occupation by a group when a lack of barriers (ecological or climactic, for example) and the presence of favorable demographic conditions allow them to increase their territory. The “Out of Africa” migration was probably not a single event or voyage, but rather a more or less continuous flow of variable volume. There may have been various “Out of Africa” movements, and also several “Into Africa,” reentries that are not technically returns, because hominins do not “go home.” Instead, they expanded the diameter of their territory whenever nothing kept them from doing so.

Arguably, genetic evidence continues to suggest that modern humanity comes mainly from a process of dispersion that took place around 50,000 years ago

Finally, 300,000-year-old fossil remains at Jebel Irhoud in Morocco shed new light (new questions?) on our species’ origin. While those specimens lack some of the features considered exclusively Homo sapiens (such as a chin, vertical forehead or high, bulging cranium), many researchers consider them the oldest representative of our lineage. The novelty lies not so much in their age as in their location. Until recently, most African fossils attributed to our species were found in regions of East or South Africa, not in the North. This and other fossils finds on that continent lend weight to the hypothesis that we originate from not one, but various populations that came to inhabit far-flung regions of the enormous African continent and maintained intermittent genetic exchanges. Homo sapiens would thus have evolved along a more cross-linked and nonlineal path than previously thought. This theory, now known as “African Multiregionalism,” suggests that the deepest roots of Homo sapiens are already a mixture, a melting pot of different populations of highly varied physical and cultural characteristics. Curiously, the term “multiregionalism” refers to another of the major theories proposed during the twentieth century to explain Homo sapiens’ origin. Unlike “Out of Africa”, “Multiregionalism” maintained that our species grew out of the parallel evolution of various lineages in different parts of the world, and this theory also observed genetic exchanges among those parallel groups. Surprisingly, the last decade has seen the two poles (Out of Africa and Multiregionalism) growing ever closer together.

The Legacy of the Past

Both genetic studies and fossil evidence from the last ten years offer a more diverse, rich, and dynamic view of our own species. From its origin in Africa to hybridization with Neanderthals and Denisovans, Homo sapiens emerges as a melting pot of humanities. Many of the keys to our successful adaptation as we conquered ever-wider territories and changing environments may well be the result of precisely the cosmopolitan miscegenation that has characterized us for at least the last 200,000 years. This admixture not only does not weaken our identity as a species; it is probably part and parcel of our idiosyncrasy.

Human evolution rests precisely on biological diversity, an advantageous and versatile body of resources on which nature can draw when circumstances require adaptive flexibility. Endogamic and homogeneous species are more given to damaging mutations, and it is even possible that the Neanderthals’ prolonged isolation in Europe over the course of the Ice Age may have made them more vulnerable in the genetic sense. Part of the flexibility that characterizes us today was received from other humans that no longer exist. We are the present and the future, but we are also the legacy of those who are no longer among us.

Both genetic studies and fossil evidence from the last ten years offer a more diverse, rich, and dynamic view of our own species. From its origin in Africa to hybridization with Neanderthals and Denisovans, Homo sapiens emerges as a melting pot of humanities

Despite being from species who probably recognized each other as different, humans and others now extinct crossbred, producing offspring and caring for them. This inevitably leads us to reflect on current society and its fondness for establishing borders and marking limits among individuals of the same species that are far more insurmountable than those dictated by biology itself. Our culture and social norms frequently take paths that seem to contradict our genetic legacy. How would we treat another human species today? Why are we the only one that survived? Would there even be room for a different form of humans? Would there be room for difference? What is our level of tolerance toward biological and cultural diversity?

We continue to evolve. Natural selection continues to function, but we have altered selective pressures. Social pressure now has greater weight than environmental pressure. It is more important to be well connected than to enjoy robust health. With the rise of genetic editing techniques, humans now enjoy a “superpower” that we have yet to really control. Society must therefore engage in a mature and consensual debate about where we want to go, but that debate must also consider our own evolutionary history, including our species’ peculiarities and the keys to our success. By any measure, what made us strong was not uniformity, but diversity. Today, more than ever, humanity holds the key to its own destiny. We have become the genie of our own lamp. We can now make a wish for our future, but we have to decide what we want to wish for. We boast about our intelligence as a species, but what we do from now on will determine how much insight we really possess. In ten, twenty, or one hundred years, our past will speak for us, and it will be that past that issues the true verdict on our intelligence.

Bibliography

—Ackermannn, R. R., Mackay, A., Arnold, L. 2016. “The hybrid origin of ‘modern humans.’” Evolutionary Biology 43, 1–11.

—Gittelman, R. M., Schraiber, J. G., Vernot, B., Mikacenic, C., Wurfel, M. M., Akey, J. M. 2016. “Archaic hominin admixture facilitated adaptation to out-of-Africa environments.” Current Biology 26, 3375–3382.

—Groucutt, H. S., Grün, R., Zalmout, I. A. S., Drake, N. A., Armitage, S. J., Candy, I., Clark-Wilson, R., Louys, R., Breeze, P. S., Duval, M., Buck, L. T., Kivell, T. L. [… ], Petraglia, M. D. 2018. “Homo sapiens in Arabia by 85,000 years ago.” Nature Ecology and Evolution 2, 800–809.

—Hershkovitz, I., Weber, G. W., Quam, R., Duval, M., Grün, R., Kinsley, L., Ayalon, A., Bar-Matthews, M., Valladas, H., Mercierd, N. Arsuaga, J. L., Martinón-Torres, M., Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., Fornai, C. […]. 2018. “The earliest modern humans outside Africa.” Science 359, 456–459.

—Hublin, J. J., Ben-Ncer, A., Bailey, S. E., Freidline, S. E., Neubauer, S., Skinner, M. M., Bergmann, I., Le Cabec, A., Benazzi, S., Harvati, K., Gunz, P. 2017. “New fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco and the pan-African origin of Homo sapiens.” Nature 546, 289–292.

—Kuhn, T. S. 2006. La estructura de las revoluciones científicas. Madrid: Fondo de Cultura Económica de España.

—Liu, W., Martinón-Torres, M., Cai, Y. J., Xing, S., Tong, H. W., Pei, S. W., Sier, M. J., Wu, X. H., Edwards, L. R., Cheng, H., Li, Y. Y., Yang, X. X., Bermúdez De Castro, J. M., Wu, X. J. 2015. “The earliest unequivocally modern humans in southern China.” Nature 526, 696–699.

—Martinón-Torres, M., Wu, X., Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., Xing, S., Liu, W. 2017. “Homo sapiens in the Eastern Asian Late Pleistocene.” Current Anthropology 58, S434–S448.

—Méndez, F. L., Poznik, G. D., Castellano, S., Bustamante, C. D. 2016. “The divergence of Neandertal and modern human Y chromosomes.” The American Journal of Human Genetics 98, 728–735.

—Meyer, M., Arsuaga, J. L., de Filippo, C., Nagel, S., Aximu-Petri, A., Nickel, B., Martínez, I., Gracia, A., Bermúdez de Castro, J. M., Carbonell, E., Viola, B., Kelso, J., Prüfer, K., Pääbo, S. 2016. “Nuclear DNA sequences from the Middle Pleistocene Sima de los Huesos hominins.” Nature 531, 504–507.

—Scerri, E. M. L., Thomas, M. G., Manica, A., Gunz, P., Stock, J. T., Stringer, C., Grove, M., Groucutt, H. S., Timmermann, A., Rightmire, G. P., d’Errico, F., Tryon, C. A. […] Chikhi, L. 2018. “Did our species evolve in subdivided populations across Africa, and why does it matter?” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 33, 582–594.

—Slon, V., Mafessoni, F., Vernot, B., de Filippo, C., Grote, S., Viola, B., Hadinjak, M., Peyrégne, S., Nagel, S., Brown, S., Douka, K., Higham, T., Kozlikin, M. B., Shunkov, M. V., Derevianko, A. P., Kelso, J., Meyer, M., Prüfer, K., Pääbo, S. 2018. “The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father.” Nature 561, 113–116.

Comments on this publication