Rarely have we known with such certainty what will be the dominant scientific topic in the coming year. It is clear that in 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to be the focus of a large part of the scientific research effort, particularly in relation to the vaccines that will be rolled out across the globe over the course of this year. But there will also be important developments in other fields of science, in a year in which climate change and Mars are two of the other stories sure to hit the scientific news headlines.

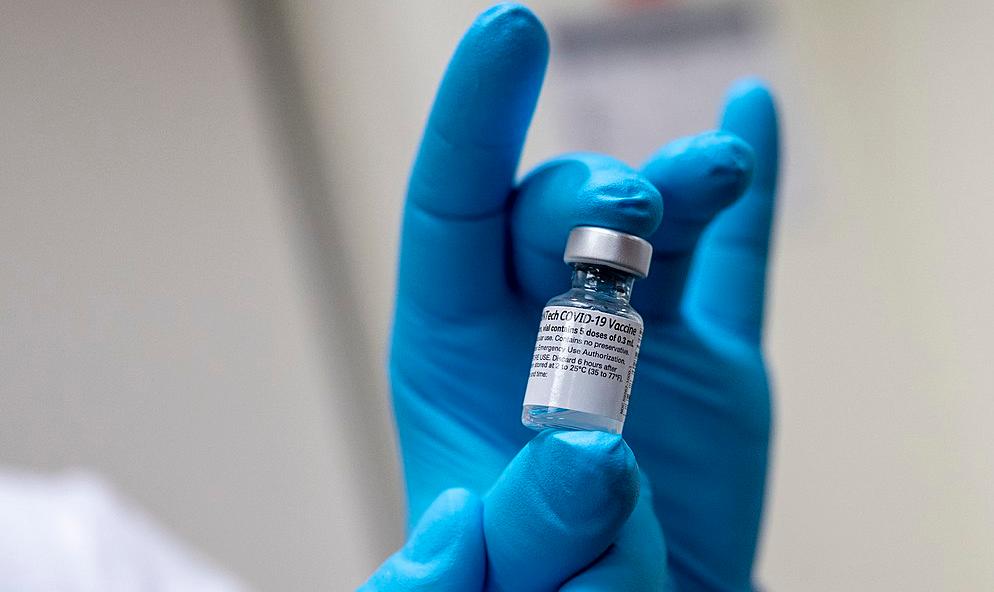

The year of vaccines

If 2020 was the year of the attack, 2021 will be that of the counter-attack. In record time, the power of human ingenuity has been able to overcome the scourge of the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus with a seemingly infinite number of vaccines, some of which are already being distributed around the world or will be soon: Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna-NIAID, Sinopharm, Sinovac or Russia’s Sputnik V. Over the course of the year, these will be followed by jabs developed by Oxford-AstraZeneca, Novavax, Janssen and others. In the coming months, the work of many scientists will shift to focusing on collecting, processing and analysing the vast amount of data that will be generated by this unprecedented global immunisation campaign.

It is likely that not all the vaccines will be successes. There will be cases of drug interactions or side effects, real-world effectiveness may not match the efficacy observed in clinical trials, and the population might become impatient if the effect on contagion is not immediate, since herd immunity will need to be achieved if we are to tame the pandemic. In the meantime, researchers will be able to use the data generated to optimise vaccine deployment.

It is uncertain whether more effective treatments for COVID-19 will be available by 2021, perhaps in the form of multi-drug cocktails. However, we can be confident that this year we should come a little closer to answering one of the great questions of the pandemic: the origin of the virus. In January, the World Health Organisation will launch a major investigation to trace the first steps of the coronavirus in Wuhan, and perhaps in other regions of China and the world as well. The search will be enormously complicated and has no guarantee of success, but it is possible that valuable conclusions will be drawn for the prevention of future emerging viral threats.

The climate we had forgotten about

The pandemic has in part suppressed global concern about climate change, but ignoring problems does not make them go away. This is demonstrated by the mounting evidence collected by scientists over the past year, reminding us that this global scourge has not been abated by the restrictions forced by the pandemic, but is accelerating. The more pressing crisis of the coronavirus forced the postponement of the United Nations COP26 conference, which is now scheduled to begin on 1 November in Glasgow. After the lack of progress made at Chile’s COP25 in Madrid, experts see this new meeting as the last chance to boost emissions reduction efforts in order to comply with the Paris agreement and to keep the temperature rise below 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels. There are high hopes that the new US president, Joe Biden, will reverse his predecessor’s decision to abandon the Paris agreement and take on new and more demanding commitments in the fight against climate change.

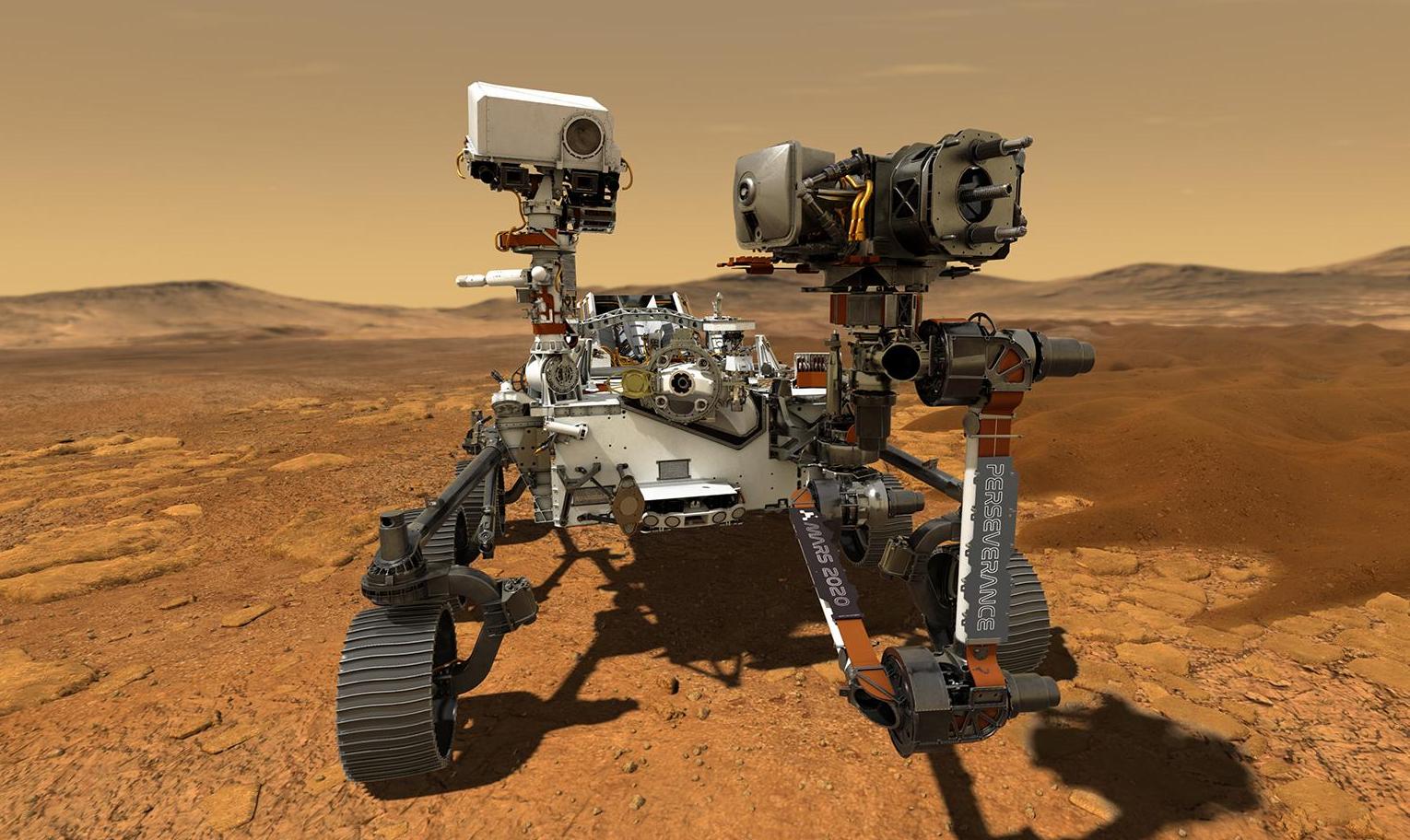

The new Martians

If all goes according to plan, in 2021 the long exclusivity of US-led missions in the exploration of the Martian surface will finally be broken. Unfortunately, the Euro-Russian bid, the second phase of ExoMars, which should have been launched in 2020, had to be delayed until 2022 due to problems with the probe’s parachutes. But better luck was enjoyed by Chinese mission Tianwen-1 (formerly called Huoxing-1), which launched in July 2020 and is expected to land a robotic vehicle on the surface of Mars on 23 April, in addition to maintaining a device in orbit.

For its part, NASA will not be left behind: on 18 February, the Mars 2020 mission will place a new rover on Mars, Perseverance, which will be joined by an absolute first, the Ingenuity drone, the first device to rise above the surface of another world. The Chinese and American missions will scan the Martian soil for possible traces of past or present habitability. Finally, the Al Amal/Hope probe from the United Arab Emirates will remain in orbit to study the climate and meteorology of Mars, a giant step forward for space science and technology in the Arab countries.

Eyes and ears turned to space

After a quarter of a century of waiting, on 31 October we will finally see the launch of the successor to the Hubble space telescope, which has rendered such outstanding service to the exploration of the universe and has provided us with countless images that are as valuable as they are awe inspiring. NASA’s new James Webb Space Telescope, in collaboration with ESA and the Canadian Space Agency, is considerably larger than its predecessor and more sensitive, particularly in the infrared band, allowing it to peer through clouds of dust and gas to observe older, more distant and fainter stars and galaxies that were inaccessible to Hubble.

If the James Webb will be our new great eye in space, we will not be without ears either. Late last year we mourned the destruction of the iconic Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico, for decades the largest in the world. But at any rate, in 2021 the astronomical community will have at its disposal China’s FAST, whose 500-metre diameter far exceeds Arecibo’s 305 metres. Starting this year, China will accept applications from foreign researchers to exploit the capabilities of this large facility.

Perhaps this year we will obtain new data on two intriguing scientific news items that made headlines in 2020. The possible presence in the atmosphere of Venus of phosphine, a gas that is associated with the existence of life on our planet, is still up in the air. The initial observations have been challenged, but there is still some margin for a possible confirmation.

We were also surprised by the unofficial announcement of a strange radio signal picked up by the Australian Parkes radio telescope and apparently coming from the star Proxima Centauri. Although it has not been ruled out that it is in fact simply due to interference from terrestrial technology, the signal has been described as the most promising indication of a possible alien civilisation since the famous Wow! signal in 1977. Both corners of the cosmos, Venus and Proxima Centauri, are now the focus of Breakthrough Initiatives, the programme founded by Russian-Israeli tycoon Yuri Milner and which has been firmly committed to answering the eternal question of whether there is life beyond Earth.

Comments on this publication