Although we still have much to learn about human evolution, we now know that at least ten or eleven species of our genus have walked the Earth, and that our own species probably coexisted with more than one of them. We are certain of this in the case of the Neanderthals, our mysterious indigenous Eurasian relatives who disappeared some 40,000 years ago, yet are still somehow present in our genes. Today the word “Neanderthal” is used as an insult to describe someone who is boorish, uncouth or ignorant. But contrary to this classic image of half-naked brutes, the most recent discoveries show them to be a people much more like us than we thought. Here is what the latest science tells us about what Neanderthals were actually like.

More heavily built, but not very different

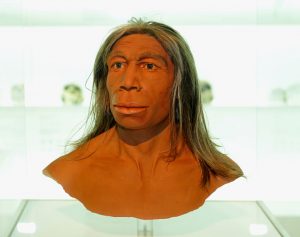

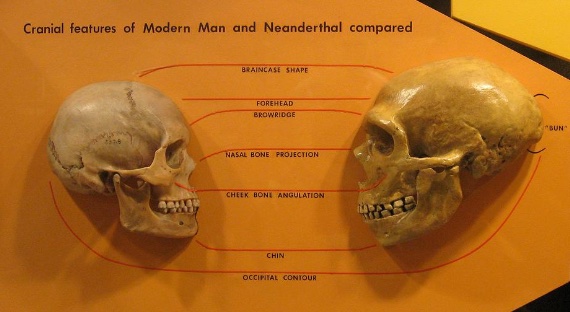

Some modern reconstructions, such as the one in the Neanderthal Museum in Germany that shows a Neanderthal man dressed in a suit jacket, present us with an individual who is slightly different from us, but unmistakably human. However, there were clear physical differences: their build was stockier and more muscular; their stature was shorter than that of modern humans; their skull was larger and more flattened, with the forehead and chin sloping backwards; their eyebrows and nose were prominent. Their large nostrils may have facilitated air intake during intense physical activity and warmed it in cold climates. Their teeth were distinctive, somewhat different from ours and those of other human species. In short, they were physically strong and well adapted to a cold and hostile environment.

A larger brain, but perhaps less capable

Contrary to their classic primitive image, the truth is that Neanderthals had a slightly larger brain than ours, in keeping with their larger cranial cavity and proportionate to their stocky build. But this does not imply that it had a similar development to ours: using brain organoids—tiny masses of neurons created in vitro from stem cells that simulate brain development—researchers have found that the Neanderthal version of a gene called TKTL1 produces fewer neurons in the neocortex, the region associated with higher cognitive processes. Another experiment found that the precursor cells for these neurons functioned worse in Neanderthals.

Did they talk?

One thing we will never know for sure is whether Neanderthals ever developed a language as articulate and rich as ours. The sequencing of the Neanderthal genome has shown that they shared with us certain evolutionary changes in the FOXP2 gene, which is involved in the development of language, although there are also differences in this and other genes related to speech. In terms of the necessary anatomical features, their hyoid bones—in the neck above the larynx—and ear bones were similar to ours, and computer reconstructions suggest that the vocal apparatus may have been akin to that of modern humans. However, this is a debate that has yet to be settled, although many researchers support the idea that the complexity of their activities would not have been possible without a language that allowed advanced communication.

Skilled craftsmen, but not very innovative

The skill of the Neanderthals as toolmakers was revealed with the discovery of the first artefacts in the 19th century. The lithic industry they practised, known as Mousterian, includes numerous stone tools and points, although it is still debated whether they had throwing weapons. Some researchers suggest that their weaponry may have been less sophisticated than that of Homo sapiens, and that this may have made a difference in battles between the two groups. One thing that puzzles experts, however, is that there doesn’t seem to have been any innovation in their technology for more than 100,000 years. One study has suggested that if Neanderthal communities were small, the diseases of old age may have made it difficult to pass on knowledge.

Builders, hunters, fishermen and artists?

Neanderthals are known to have made clothing from animal skins, used birch tar as an adhesive, mastered fire, built hearths for their campfires and cooked. Remains of more complex constructions have been found; for example, in the French cave of Bruniquel, circles made from fragments of stalagmites were discovered, the original function of which is unknown but which suggest a possible ceremonial significance. A site in Ukraine contains a large number of mammoth bones, which researchers believe were part of a dwelling structure set up by Neanderthals. In addition, of course, they hunted, fished in the sea and rivers, and engraved patterns and possibly painted on cave walls.

Neanderthal thought

One of the great debates about Neanderthals is whether they possessed symbolic thought or the capacity for abstraction, a trait associated with the superior intelligence of modern humans. Evidence is sought in art, the use of ornaments, burials and music, but the debate is not yet settled. It is known that they buried their dead, but the real purpose of this practice is unknown, as are any of the possible examples of art. A peculiar case is that of the Divje Babe flute, a piece of cave bear femur found in Slovenia in 1995, which has two spaced holes. Some researchers suggest that it is a real musical instrument, the oldest known, which would confirm the symbolic thinking of Neanderthals. Other experts suggest that the holes are merely the accidental product of a carnivore’s bite.

Neanderthal society

All of this paints a picture of Neanderthals that is far removed from the club-wielding caveman so typical of ancient depictions, and one that many people still have in mind when they use “Neanderthal” as an insult. Yet much is still unknown about what Neanderthal society was like. Their populations were probably small and their communities more isolated than those of sapiens, perhaps with less social organisation, which may be linked to their decline. However, recent analysis of their ancient genomes has shown that women migrated to other communities, suggesting a social structure that avoided inbreeding.

Did they really go extinct?

Of course, Neanderthals no longer exist today, although there is no consensus on what led to their disappearance; their small population and low genetic diversity, competition with Homo sapiens under unfavourable conditions, changes in climate or the transmission of disease may have formed a lethal cocktail that spelled doom for the survival of their species. But some scientists offer a less catastrophic vision. We know that Neanderthals and sapiens came together to procreate, resulting in the 2% of Neanderthal genes that all non-African people carry in their DNA today. Interestingly, this hybrid lineage is the argument put forward by those who argue that we are in fact the same species.

But, in any case, this shows that there was at least some integration in which the better-adapted species triumphed: our ancestors 45,000 years ago had 10% Neanderthal DNA in their genome, a proportion that declined rapidly, suggesting that some of those genes were deleterious. In a sense, you could say that they were diluted in us, and that we might see ourselves as improved Neanderthals.

Comments on this publication