In November 1827, a series of murders began in Edinburgh that kept the city on edge for nearly a year. The resolution of the case revealed a surprising connection with the flourishing of science in the capital of Scotland.

In the middle of the 18th century, six hundred taverns flourished in the small city of Edinburgh to quench the thirst of only forty thousand inhabitants. It was a dirty, smelly and yet very beautiful city: the castle looked down from the top of an extinct volcano with that absent and haughty air that castles possess, and 1,706 paved metres (totalling a little more than a mile) separated it from the Royal Palace of Holyroodhouse. Between the two, small perpendicular streets like the bones of a fish welcomed the rich and the poor —without too much difference— in narrow buildings some four or five storeys high.

Along these few streets walked some clever men who would influence a large part of the destiny of the world, in a serendipity that would be difficult to repeat. Joseph Black, a chemist, isolated carbon dioxide for the first time and became a good friend of James Watt, whose modification of the steam engine would jump start the Industrial Revolution. James Hutton preferred the observation of the formations of the landscape surrounding the city, which he would condense into his Theory of the Earth, which formed the basis of a new science: geology. Meanwhile, Colin Maclaurin, mathematician and Newton’s pupil, gave his surname to the famous Maclaurin Series. And then there was Adam Smith, whose masterpiece, The Wealth of Nations, sustains the edifice of economic liberalism. As the Scottish Enlightenment proceeded, Edinburgh renounced the nickname Auld Reekie —”Old Smokey”, as its inhabitants affectionately called it— rebranding itself with a nobler title: “Athens of the North”.

This intellectual flourishing lasted throughout the first decades of the 19th century and had a strange side effect: a series of atrocious murders, among the most disconcerting that had been seen in the whole of the United Kingdom. On those few streets that were Edinburgh, specifically the ones that made up the West Port neighbourhood, Margaret Docherty, a woman of Irish origin better known as Madgy, was looking for a son she hadn’t set eyes on in years. On the night of October 31, 1828 she was seen for the last time. The “Athens of the North” had been nervous for a year with the disappearance of fifteen (sixteen counting Madgy) of its inhabitants.

Body snatchers

A detective like Sherlock Holmes could have solved the case, applying the deductive method and investigating the context of the Scottish Enlightenment. In parallel to the development of other sciences, Edinburgh had become one of Europe’s leading centres for anatomical studies, along with Bologna and Padua; however, its success led to a serious problem: the scarcity of cadavers for dissection. At that time, Scottish law required that bodies used for medical research come only from executed criminals or suicide victims, which led to the emergence of a new profession based on strength and ingenuity: that of body snatchers or “resurrection men”, who desecrated graves in search of freshly buried corpses to sell to anatomy teachers.

In response, the cemeteries increased their security measures, complicating the business of grave robbers and the investigations of anatomists. Could any of the interested parties have gone too far? Any reasonably competent detective investigating that wave of disappearances in 1828 would have attended the public dissections of corpses taking place in anatomy theatres, would have followed up on rumours that some students claimed to have seen the body of beggar James Wilson on the dissection table (the 15th missing person was a young hunchback known as Daft Jamie), and would have interrogated the anatomy teachers to certify the origin of the cadavers. The case could have been resolved earlier with such deductive logic, and even the death of Madgy, the final victim, could have been prevented. But no one asked those questions.

The unexpected links of these murders with science were revealed in a much more prosaic way. On the night of her disappearance, Madgy had been seen in the company of two compatriots, William Burke and William Hare, who ran a boarding house near Grassmarket. They managed to convince her to accompany them to the house and there they got her drunk. The strange attitude of Burke and Hare aroused the suspicions of a couple of guests, who discovered Madgy’s body the next day and ran to inform the police. When they arrived, the officers did not find the body, but they did find the remains of her bloody clothes. After they were arrested, Burke and Hare crumbled under an intense interrogation and their confessions led the officers to the surgery of the famous anatomist Robert Knox, a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in Edinburgh and curator of its Museum of Comparative Anatomy. There, what was left of poor Madgy awaited them.

The anatomist denied any knowledge of murders and argued that two Irishmen, Burke and Hare, were supplying him with the bodies for his successful practical anatomy classes. In total, the two men sold 16 bodies to Knox, who paid them about 10 pounds for each one. The series of disappearing bodies began with the death of a sick tenant in their boarding house, who hadn’t paid them for several weeks. To compensate for that economic loss, Burke and Hare sold the body to Knox and, once that path was opened, they chose to hasten the end of the 16 victims, mostly poor and lonely people, who were first plied with copious amounts of alcohol. The spiral of truculence, alcohol and carelessness culminated in Madgy’s death. However, for the victims’ killers, fate held a certain poetic justice in store.

The fate of Burke, Hare and Knox

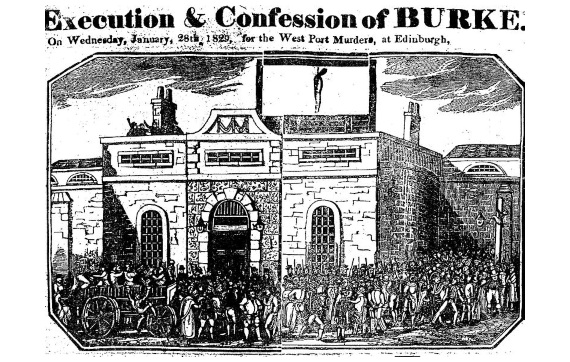

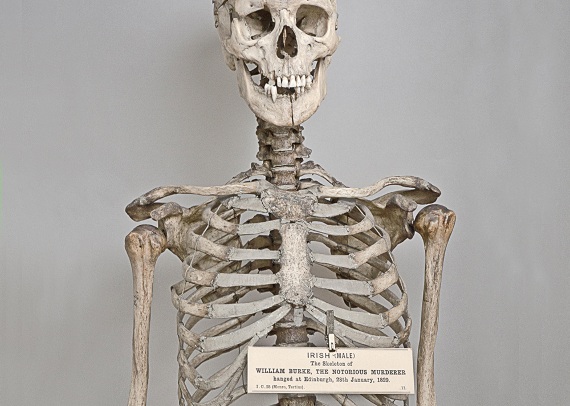

Burke was hanged and his corpse publicly dissected in the anatomy theatre of the Old College of Edinburgh University School of Medicine. There were long queues of students wanting to witness the dissection, leading to riots and even the intervention of the police in a process that lasted two hours. His skeleton remains to this day on display at the university’s Anatomical Museum with a sign reading: “Irish (Male). The skeleton of William Burke, the notorious murderer hanged at Edinburgh, 28th January, 1829. Dissected by Monro, Tertius.”

Hare’s fate was less clear cut. After confessing and laying all the blame on Burke, he managed to get himself released from jail. There are two versions circulating as to what he did next: either he ended up living blind and poor on the hard streets of London or he returned to his native Ireland. The anatomist Dr Knox had to face public rejection. Although he was exonerated of all guilt, his private anatomy classes languished; while he tried unsuccessfully to open a new school in Glasgow, all his applications for various academic positions in the medical faculty of the University of Edinburgh were rejected. In 1842, he left the Scottish capital for London and never returned.

A final unexpected consequence of Burke and Hare’s crimes was the passage in 1832 of the UK Anatomy Act, which granted licensed anatomists legal access to unclaimed corpses —those of people who died in prisons, hospitals or in the foul-smelling streets— and to anyone who agreed that their body should be donated to medical science. The case of Burke and Hare has inspired films, stories such as The Body Thief by the illustrious Scotsman Robert Louis Stevenson, and even a disturbing nursery rhyme sung when jumping rope:

“Up the close and down the stair,

Up and down with Burke and Hare.

Burke’s the butcher, Hare’s the thief,

Knox the man who buys the beef”

Comments on this publication