“Any victory in the absence of Russian athletes will have a different flavor.” This is how Vladimir Putin, president of Russia, inveighed against the International Olympic Committee (IOC) for the expulsion from the 2016 Rio Olympics of the athletes suspected of doping. None of Russia’s 68 track and field athletes will compete, nor will 40 other athletes from other disciplines such as swimming, rowing and canoeing. All of them had stains of doping in their background and many of them had been part of a sophisticated government network that hid it. “It was a case of state doping worthy of a spy novel,” thundered the experts who read the McClaren report in which the conspiracy was revealed. The anti-doping agencies demanded a severe punishment against Russia. They wanted to end a practice that has accompanied the Games since its origin and that first appeared with the same sport: track and field.

The proof of this origin is in Greece, where six statues in a row line the path to the arena of the Peloponnese, some 175 kilometers from Athens. It is the walk of shame for the brazen cheaters of the ancient Olympic Games. There we find written the names of the Greek athletes who broke with the standards of the Games, which were founded in 776 B.C. as the forerunners of the ones we know today. The punishment at the time was not only expulsion from the competition, but also a black mark for all eternity. That’s how seriously the ancients took the rules; however, it is not clear in any document that doping was considered cheating.

The aim of the athletes was, in most cases, to increase strength and overcome fatigue. To do so, they consumed stimulants such as brandy, various types of wine, hallucinogenic mushrooms or sesame seeds. The Spartan Charmis of Laconia won the speed running competition following a diet of dried figs. Diets of mushrooms and meat were experimented with, and there were even cooks that supplied pieces of bread with analgesic properties, cooked with spices extracted from the poppy plant. For the most part, these primitive stimulants had a natural origin.

It would be another 1,503 years before the Olympic competition would rise again. But before this, in the middle of the nineteenth century, there were already cases of doping being recorded in modern competitions. These cases coincide, not by accident according to experts, with the beginnings of modern medicine. In 1850, a period began that is marked by the arrival of scientific experimentation on the anabolic effects of hormones.

“In the last third of the nineteenth century, stimulant use among athletes was common and, what’s more, there was no attempt to link drug use with the expulsion of the athletes,” explains Charles E. Yesalis, a professor at Pennsylvania State University, in his study History of Doping in Sport. One of the first documented cases of this epoch took place in 1865 when the consumption of an unidentified stimulant drug in a swimming event in the Amsterdam canals was described.

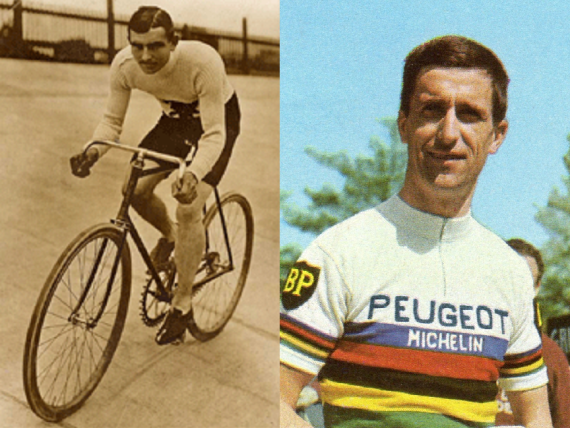

The experiments continued until the first death of an athlete attributed to doping began to raise alarm bells. This was the case of Arthur Linton, an English cyclist who died in 1896 from an alleged overdose of ephedrine that he had consumed two months earlier to win the Bordeaux-Paris race.

Doping in the modern Olympic Games

Cases of doping did not disappear with the return of the Olympic competitions in 1896; on the contrary, in many cases they became more visible. In the Games in St. Louis (USA) in 1904, the winner of the marathon Thomas Hicks collapsed just after crossing the finish line. The doctor of the American runner had supplied him with several injections of strychnine and slugs of brandy at different moments in the race when he was flagging. The comments of the doctor who was attending to Hicks passed out on the ground reflected the thinking of the time: “The marathon races, from a medical point of view, demonstrate the great benefit that drugs have for athletes.”

From then on sports entered an epoch when doping became popular: alcohol, caffeine, cocaine, strychnine… everything was acceptable. Only in those cases where the athlete was doped involuntarily to worsen their performance was it denounced.

In the 1967 Tour de France, the Englishman Tom Simpson, 29, collapsed and died in the middle of the legendary ascent up Mont Ventoux. The autopsy revealed that he had mixed amphetamines and alcohol, a combination that proved fatal in the heat and effort of that stage. It was the first death from doping that was televised. The impact was so great that that same year the IOC was forced to bring out some anti-doping regulations.

However, the effect of the new rules was not what was hoped for and doping episodes would be repeated again and again throughout the history of the Games. Athletes even recognized their substance use in public without shame; publications such as Track and Field News defined anabolic steroids as the “Breakfast of Champions“. “We will see whose are better: their steroids or mine,” said one weightlifter to the Los Angeles Times in 1971.

In 1988, 20 years after the prohibition of doping, an investigation by the New York Times concluded that at least half of the athletes who competed in the Seoul Games –marked by the disqualification of Ben Johnson, champion of the 100m dash– were taking anabolic steroids. There were official national doctors and pharmacologists preparing drugs for their teams without consequences.

Attack on the Olympic Committee

Perhaps the attitude changed the same year that some feared the end of the world. At the Sydney Games in 2000, dozens of publications and experts attacked the IOC in unison for its lack of involvement in ending what had by then become a scourge. Articles such as “Dirty Games” described a growing epidemic of drug use in Olympic sports. They began to speak against the protagonists themselves. Frank Shorter, Olympic marathon champion and spokesperson for the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, not only recognized the magnitude of the problem but also warned that the consequences went far beyond the Games.

Unlike the former concoctions, drugs such as growth hormones have side effects such as loss of vision, the risk of heart failure or the increased likelihood of diabetes and tumors. For anabolic agents, which are normally used to interrupt growth, the greatest damage occurs in the liver. Suffering a pulmonary embolism, hypertension, anemia or cancer are just some of the risks of doping with EPO (Erythropoietin) against which the current anti-doping agencies warn. EPO, a hormone that serves to increase the production of red blood cells and thus provides the athlete with more strength, has been the drug most used by athletes in recent decades. This was largely due to the fact that it was undetectable until the year 2000. Now, all anti-doping agencies warn against this and other types of substances; however, as in the case of Russia, this hasn’t prevented the athletes themselves and their teams from finding other ways to hide it.

Current doping scandals have rocked the start of the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. But looking back toward the source of this sporting event in ancient Greece, the professor of classical history at the University of Maryland (United States) Hugh Ming Lee does not believe that doping would have been a scandal back then. Lee points out the strong awareness that the Greeks had of human weakness: “If Hercules was vulnerable, why wouldn’t human athletes be the same?”.

Comments on this publication