Physicists had arrived at the end of the 19th century with a very high opinion of themselves, after the impressive feats of mythical scientists such as Faraday and Maxwell. The former managed to link electricity and magnetism thanks to his brilliant intuition, while the latter went even further: out of sheer mathematical exuberance, he devised theoretical formulas that unified both phenomena and also explained light as an electromagnetic wave. Everything seemed to fit. Albert A. Michelson, who with his astonishing experiments succeeded in measuring the speed of light, took it for granted in 1894 that the great principles of physics were now settled and that from then on it would be merely a question of polishing and refining: “The future truths of physical science are to be looked for in the sixth place of decimals…”

This prediction of the end of physics, which is falsely attributed to Lord Kelvin, was shattered by three remarkable discoveries over the following three years: X-rays (1895), radioactivity (1896) and the electron (1897), which once again shifted the paradigms of physicists—who, just as they were beginning to assimilate these revolutionary developments, saw Planck launch quantum mechanics (1900) without really giving credence to his own theory.

AN INVISIBLE LIGHT TO SEE NEW WORLDS

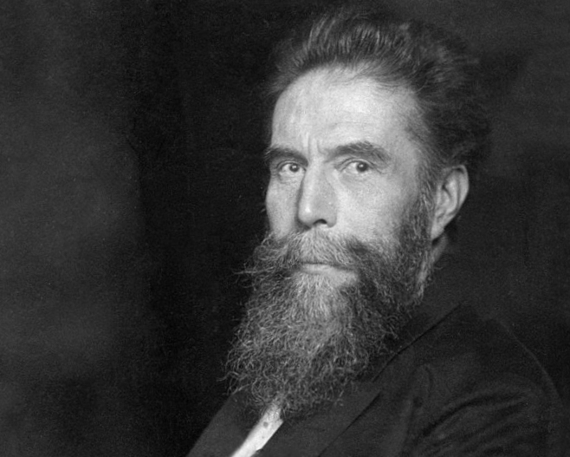

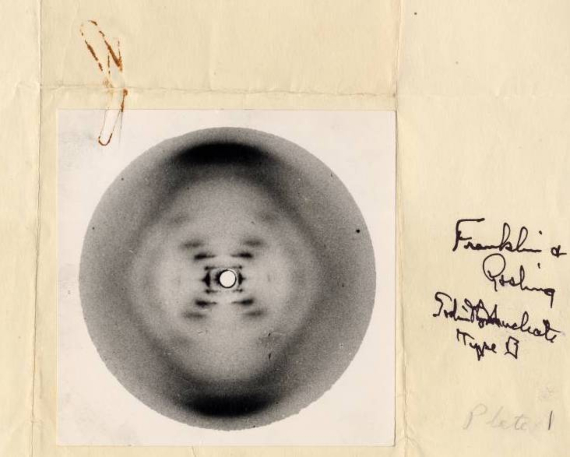

X-rays, discovered by the German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen (27 March 1845 – 10 February 1923), were the first of those scientific breakthroughs that literally changed our view of the world. Röntgen, who himself took the first radiographic images in history, saw this from the very beginning. But beyond their medical applications, which today we see as an everyday occurrence, this new unknown radiation (hence the letter of its name) was the key to being able to visualize in 3D the penicillin molecule in 1945 (which led to the mass production of the first antibiotic) or to understanding in 1953 that DNA was a double helix (which finally unravelled the enigma of the genetic code). These and other discoveries earned Nobel Prizes for many scientists, who used X-rays to see and understand the unseen. And this radiation has revealed everything from tiny structures within cells (thanks to the X-ray microscope) to violent astronomical phenomena such as galactic cannibalism in remote parts of the universe (detected by X-ray telescopes).

120 years later, and with all those achievements along the way, it makes even more sense that the first Nobel Prize in Physics in history went to Röntgen, in 1901, culminating the improbable scientific career of a not very brilliant student. His academic career was marred by an incident at high school, in which a mocking caricature of a teacher—which the teenage Wilhelm denied having drawn but refused to confess who the author was—led to his expulsion and the impossibility of attending university in Holland, where he lived. He managed to become a university student in Switzerland through the Zurich Polytechnic Institute (the same one where Einstein studied) and eventually became a full professor at the University of Würzburg, without having particularly stood out in his academic career.

It was in this position that Wilhelm Röntgen surprised the world with his great discovery. He was one of many scientists who, like William Crookes, were researching with vacuum tubes, and everything points to the fact that other scientists had witnessed the phenomenon before, but he was the first to stop and study it. On 8 November 1895, Röntgen observed a faint green glow on an external fluorescent screen, outside the tube that he had completely covered with black cardboard. During the 19th century, physicists had come to accept that there were forms of light that were invisible, but they were not prepared to believe that invisible light could pass through opaque materials such as cardboard or skin (but not denser ones such as metals or bones); much less could they imagine that it could be used to see things that had been impossible to see until then, such as the inside of the human body. However, Röntgen did.

RÖNTGEN RAYS AND PROFESSOR X

At first, distinguished scientists such as Lord Kelvin rejected Röntgen’s observations and thought it was a hoax, but the meticulous experiments and details provided by the German researcher finally convinced them. Although his talent was perhaps not as impressive as other brilliant scientists, in the history book of science his name appears alongside theirs, and he shared with them a lack of prejudice. “I did not think, I simply investigated,” said Wilhelm Röntgen when he was asked about the shocking conclusions of his research On a new kind of rays.

In many countries this surprising radiation is still called “Röntgen rays”, although he always rejected the limelight (today his name is remembered for the unit for measuring radiation exposure and also for a highly radioactive chemical element). He did not attend the Nobel Prize award ceremony nor did he ever want to apply for patents related to his discovery, claiming that it was knowledge that belonged to mankind—a behaviour in sharp contrast to that of patenting machines like Edison or brilliant engineers like Tesla, who wanted to dispute Röntgen’s discovery of X-rays. Moreover, he donated all the Nobel money to his university and so died poor in 1923, with his savings consumed by inflation after the German defeat in the First World War. With no desire for grandeur, he asked that after his death his laboratory notebooks be burned, which prevents us from exploring some details of the research that reserved for him a place in history. The famous discoverer of Röntgen rays thus ended up, paradoxically, as a forgotten and almost unknown Professor X.

Comments on this publication