Following the intellectual slowdown that occurred in the West during the Middle Ages, seventeenth-century Europe experienced a mathematical renaissance with its epicentre in France. Descartes emerged during this resurgence of knowledge, a brilliant philosopher who dared to question the predominant scientific thinking of his era, opting for reason, experimentation and observation in the face of tradition and authority. It is from him that we get the famous phrase: “I think, therefore I am.” With this idea he wrote the Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences, a philosophical treatise in which he also developed analytical (or Cartesian) geometry, one of the richest veins of mathematical thought.

Since the time of Plato, more than 2000 years ago, there had not been as intense a period of communication among mathematicians as the one that began in France in the second third of the seventeenth century. Among the protagonists of this exchange of ideas by letters was René Descartes (31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650). Born in La Haye, a town in the centre of France, Descartes was a sickly child who was forced to spend his mornings in bed, which he took advantage of by reading and studying. At the age of 20 he moved to Paris, where he came into contact with other intellectuals of the time and began to delve into one of the scientific disciplines at which he would excel: mathematics. In 1628, he moved permanently to Holland in search of a freer intellectual environment, something that he seems to have found, since the years he spent there were the most fruitful of his life and when he wrote his most popular works.

A dictionary between algebra and geometry

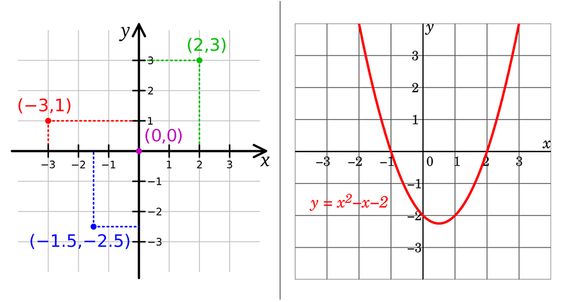

The most famous of Descartes’ treatises, the Discourse on the Method, contains the appendix Geometry that relates for the first time algebraic concepts with geometric objects, giving rise to the emergence of analytic or Cartesian geometry (from Cartesius, the name Descartes in Latin). In this new geometry, the points of the plane are identified with pairs of numbers (x, y): it is a coordinate system in which each pair gives us the position of a point with respect to two fixed perpendicular lines, called coordinate axes. Thus, each pair of coordinates specifies a single point of the plane, and each point is given by a single pair of coordinates. Descartes had devised a kind of dictionary between algebra and geometry, which in addition to associating pairs of numbers to points, allowed him to describe lines drawn on the plane by equations with two variables—x and y—and vice versa.

The novelty of this approach to analytical geometry was that it allowed geometric problems to be solved through the exclusive manipulation of algebraic expressions. Until that moment, the dominant geometry had been Euclidean, which used the ruler and the compass to solve problems. Descartes’ method worked, and was more practical, because analytical geometry represents the set of solutions of a two-variable equation, x and y, by a line in the plane. For example, an equation of the type: ax + by = c (such as 2x + 3y = 0), which is a first-degree polynomial equation, has as a set of solutions a straight line, which arises from joining all the points with x and y coordinate values that satisfy that equation. Circles and the rest of the conics are represented by second-degree polynomial equations. One example is the circumference: x2 + y2 = 4, and another the hyperbola: xy = 1. Thanks to the work of Descartes, all the ancient geometry was translated into the study of the relationships that exist between first- and second-degree polynomials—something that today is still studied in secondary school mathematics.

The challenge to Fermat

Of the relationships that Descartes established with other French mathematicians, none was as intense as the one he had with Pierre de Fermat, who also made important contributions to analytical geometry. Fermat had developed a method to obtain the tangent line to a curve at any of its points, but Descartes believed that this was not a true method, so he decided to challenge Fermat—something relatively common among the intellectuals of the time—to find the tangent line at any point of the curve described by the equation x3 + y3 – 3axy = 0, today known as the Folium of Descartes. Fermat solved the problem, provided the evidence to Descartes and demonstrated the success of his procedure, a method that laid the foundations for Newton and Leibniz to develop infinitesimal calculus.

Although the greatest achievement of Descartes was the development of his geometry, he also made important contributions in other areas. In the field of optics, he introduced the so-called refractive law, which allows us to calculate the refractive angle of light when crossing the surface that separates two media with different refractive indices (for example, air and water). Also in physics, Descartes established that rectilinear motion is the natural one, which went against the wisdom of the day that viewed uniform circular motion as being the most natural since it revealed the movement of the stars and the planets.

Today, Descartes is considered not only an illustrious philosopher, but also an outstanding mathematician and physicist. He died of pneumonia in Stockholm, only a year after accepting the invitation of Queen Cristina to be part of the Swedish court. After a long journey, not without controversy, his remains returned to France. Nowadays, at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris it is possible to contemplate Descartes’ skull, which once housed one of the greatest mathematical revolutions in history.

Comments on this publication